Beres Hammond ADD

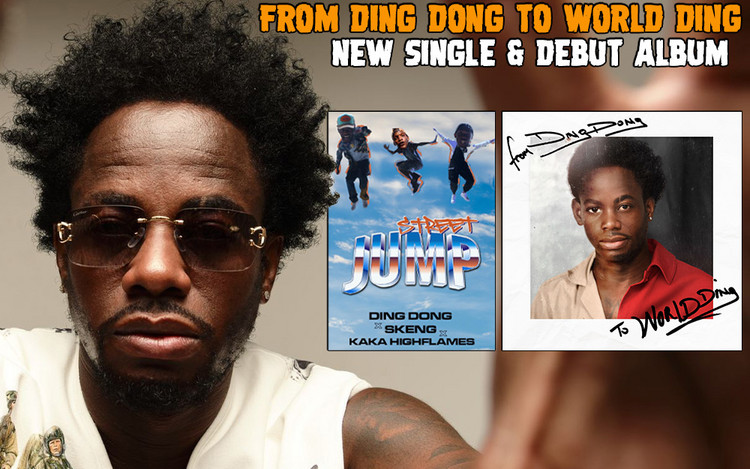

Interview with Donovan Germain - 25 Years Penthouse Records

02/19/2014 by Angus Taylor

Jamaican super-producer Donovan Germain recently celebrated 25 years of his Penthouse label with the two-disc compilation Penthouse 25 on VP Records.

But Germain’s contribution to reggae and dancehall actually spans closer to four decades since his beginnings at a record shop in New York.

The word “Germane” means relevant or pertinent – something Donovan has tried to remain through his whole career - and certainly every reply in this discussion with Angus Taylor was on point.

He was particularly on the money about the Reggae Grammy, saying what has long needed to be said when perennial complaining about the Grammy has become as comfortable and predictable as the awards themselves.

How did you come to migrate to the USA in early 70s?

My mother migrated earlier and I came and joined her in the States. I guess in the sixties it was for economic reasons. There weren’t as many jobs in Jamaica as there are today so people migrated to greener pastures. I had no choice. I was a foolish child, my mum wanted me to come so I had to come!

What was New York like for reggae then?

Very little reggae was being played in New York. Truth be told Ken Williams was a person who was very instrumental in the outbreak of the music in New York. Certain radio stations would play the music in the grave yard hours of the night. You could hear the music at half past one, two o’clock. Then Ken Williams started at WLIB doing the daytime programme. From four hours on a Saturday it expanded to all day Saturday and then it expanded to the weekend and then to seven days a week.

I contributed to the growth because at the time I was working at Keith’s Record Store and we used to get records from Jamaica every weekend. I would go to the airport and collect the records and I would always take a sample to the radio station to give to them to play.

You have been compared to Gussie Clarke in your career. Your studios were near each other geographically, you both started producing in the roots era and you both brought a sense of history and sophistication to dancehall. But Gussie actually gave you your first job as a distributor in New York. I guess you went back even further than the 70s?

We were at the same high school so I knew Gussie from when we were in school together. Me, Gussie and Augustus Pablo at the same time. We were free spirited young people who didn’t have a care in the world. We were at school having fun, we didn’t have to pay any rent or mortgage! (laughs)

Did you see in them what they would become?

No, not really. Because basically we were having fun in high school. We didn’t really have a choice in our occupation at the time. Augustus Pablo was playing his harmonica but I didn’t think at that time he had set out to be in the music industry. The thing about music is it is an addictive thing. Once you get into it you can’t leave it.

You’ve said that Gussie and Lloyd Campbell taught you the ropes as a producer - what they teach you?

Going into a studio you have to know what to listen for. You have to know the jargon to speak to the musicians and to speak to the engineer to bring to life what you want in a song. So you would basically work with them and see how they communicated what they wanted in a song – the sound and the tempo they wanted in the song, what drum sound they wanted – stuff like that. You’d listen and take note.

Your first label was Revolutionary Sounds – which specialised in roots music. In your work with Cultural Roots there is an early sign of you bringing something older to the new sound because this was one of the last of the harmony groups – a style that had ruled the 60s and 70s.

I started with the group Cultural Roots. They were young unknown people. Sly and Robbie were the musicians. That was the kind of music that they brought to the table – a music that was the voice of the people of the inner city – their hardships and their aspirations. It was using harmonies as a group with horn sections. It was a total musical arrangement with roots. It was not like today where you had some basic things as the rhythm. You had harmonies, three guitars, three or four part horn sections, keyboards aplenty and the groove was a little bit slower. That was what roots music was to me. The lyrical content was hard core – people were singing about their hardships. I used to be a roots producer when I started and I still make roots songs now. But somehow it just doesn’t resonate to me as the previous people like Burning Spear, the Gladiators and those hot topics they took on.

In past interviews you have resisted attempts to compartmentalise your work. Do you see a continuous lineage from Revolutionary sounds to Penthouse?

I think they are the same thing because my mission from day one was to work with young talented people. I didn’t set out to go with the established artists of the time. But along the way I figured I needed to have some established artists on the label to draw attention to the label like Marcia Griffiths, Delroy Wilson and Beres Hammond. They brought a certain amount of integrity to the label in terms of their presence.

You took some inspiration from Coxsone Dodd, who was in turn inspired by Motown.

Coxsone Dodd was my mentor – my idol I should say. We all have to give Coxsone credit for the fact that he had a vision to start what he did with his label. Because, don’t forget, this was a farm worker with no formal education who grew up on and loved music, who got people to record music for his sound system until it evolved into the music industry that we can be a part of today. I have to give him credit for that every single day because that’s why I believe I can take care of my family. I saw Coxsone as a person who was giving young, unknown people an opportunity to showcase their talents. I saw the success the good will and the catalogue he built up from that so I knew if I was to be successful that was the person I had to emulate.

The money to set up Penthouse came from some hits you had in the United Kingdom. What was it about that market that worked for you?

You see, to this day the English market have a different taste to what is in the States or in Jamaica. In the 80s the lovers rock phenomenon was going on in the British marketplace. Beres Hammond had this song What One Can Do which was a mega hit in the Jamaican community. But Audrey Hall, who was British born, had this British sound and we did this answer to the Beres Hammond song which became a national hit in Britain. Then we did the follow-up Smile which also became a top ten British chart hit and we also did Freddie McGregor’s Just Don’t Want To Be Lonely which became a top ten hit. These were all lovers rock songs. I wanted to conquer everywhere that reggae music was being played so I went and stayed in London for nearly three years getting a label established there.

Your mixing engineer at Penthouse was Stephen Stanley who was one of the most important and respected figures within the reggae industry – yet his contributions both inside and outside Jamaica are overlooked by the wider public.

Stephen Stanley was the best mixing engineer Jamaica had ever seen. I say that without any apology. Don’t forget Stephen Stanley was the person who did the Tom Tom Club song [Genius of Love] that was a massive hit. He was good enough that Chris Blackwell took him from Jamaica to the Bahamas to his Compass Point studio to be the resident engineer there. So he must have had some quality for Blackwell to have taken him from Jamaica and given him that post. So the other engineers at Penthouse, everyone sat with him and learned. They apprenticed under Stephen Stanley. A great engineer will take my work and make it sound twice as good as when I gave it to him! (laughs)

When did you first meet Beres Hammond in person – rather than creating answers to his songs? He had been in the business at least as long as you by that point.

I first met Beres in 1989. Beres was living in the States for a while.

Yes, he had some trouble in Jamaica and he had to leave.

Right. Then he came back to Jamaica and he wanted some studio time. In those times there weren’t a vast amount of studios around so he came to me and asked if he could rent a studio and I told him I didn’t have any because usually the studio was booked three or four weeks in advance. But every Tuesday and Thursday were automatically my days in the studio so I told him I would give him one of my days “if you sing a song for my label”. He said he would do that and the first song we did was Tempted To Touch – we have had a relationship from that day until today.

Beres is a man who rarely gives much away in interviews but he has a reputation for humour.

Yes, very very humorous! (laughs)

Give me an example of his humour.

(laughing) When we started recording the Love Affair album every night he would come to the studio he would send and buy a six pack of Guinness stout. One night I said “Beres why every night are you drinking this Guinness stout?” and he said “Take this bottle in your hand and look at the label – what do you see?” I said “I see a harp” and he said “There you go, that’s a musical instrument on the label – that’s what I drink this Guinness for!” (laughs)

Tell me about first meeting Buju Banton and likewise what kind of person he is.

Buju Banton came to Penthouse via an engineer we had by the name of Stumpy. He came for an audition and I wasn’t there when he came but I remember walking into the studio when he was being auditioned by Dave Kelly and I heard him doing his song Man Fi Dead. I called Dave Kelly to the studio after and I said “Dave, that kid have some talent but the songs that he is doing… he needs to use his talent to do some other song because the song is too graphic and violent”. But what I can say about Buju was he was totally committed to his music and he was always prepared to make a song. He had about sixty songs written in a book and I was saying “My God, this is really unusual for a young person to have all these songs written in a book!” But he was always ready to work. He was at the studio every single day. And if the studio opened at ten o’clock he would be there by ten o’clock until we closed for the night. He was very committed to his craft and very talented. Every generation gets a very talented artist. Shabba for the generation before and Buju for his generation, like I think Chronixx is right now. It was just natural for him to excel because of his commitment to the music. He didn’t compromise the standard in the music.

Teamwork, loyalty, professionalism, perfectionism – what do these concepts mean to you?

They are all a description of me. And also longevity. I believe in the longevity of relationships. Because Marcia Griffiths was at Penthouse from 1986, Beres Hammond from ’89, Tony Rebel from ’88 - and they’re all still here. All the artists that have recorded at Penthouse are still recording at Penthouse.

You’ve also maintained your relationships with England – with Mafia and Fluxy, with John from Fashion Records and Dub Vendor.

I think it was part of my DNA to build them. They helped me and I was indebted to them so I am always grateful. If these people hadn’t given me an opportunity I wouldn’t be where I am today doing this interview with you talking about my 25 years of history. Someone gave me a chance and when I went to England I met John from Fashion Records – he’s my friend to this day. When I go to London I stay at his house. Because we developed a mutual respect in the relationship. This is not about going to his store and selling some product. I believe in the relationship. If I can call on you and you do something for me you can call on me and I can do something for you. If there’s a high level of respect for what you’re bringing to the table and what I am bringing to the table then there’s an appreciation for what everyone is bringing to the table – that’s how I look at it.

You worked with Bunny Rugs from Third World who recently passed away. What are your memories of him?

Another very jovial person of high quality. Committed to the craft, loved the business and loved singing. Those are the things I would use to describe Bunny Rugs. I recorded Bunny Rugs before I even started Penthouse. For Marcia Griffiths’ first album Marcia he brought the song It’s Not Funny for me to record with Marcia Griffiths himself.

The world recently celebrated the birthday of Dennis Brown – what are your memories of Dennis?

Ah, well, I knew Dennis Brown from when I was living in the States and when I came to Jamaica I saw him and I said “Dennis you have to sing a song for me” and he said “In time, in time!” Then one day he just popped into the studio and said “OK Germain, let me hear the rhythm”. He did the song Brought Me Love and then he came back and did a song with Richie Stephens. Another night while Beres and myself were recording a track, Beres had his song Love Within the Music that is on this CD and he had said “I need to have Dennis Brown on this track” but Dennis had been very elusive so he said “We are going to lay the voices for this track tonight”. I said “How are we going to lay the voices without music?” and Beres said “Germain, we are going to lay this track down without the music tonight”. Dennis went into the studio and started to sing but he was singing a cappella and he was going off time. So Beres went into the studio, stood beside him and with his feet he kept tapping on the floor to keep time with Dennis singing his part of the song. So when you listen to the track tape you will hear Beres tapping his feet on the floor to keep time for Dennis Brown. That entire song was recorded a cappella and then we brought in Robbie Lyn who laid the instruments around the a cappella. It’s a very unique song that’s why it’s on the project. The significance of how that song was recorded is why it’s significant to this anniversary.

I’m going to finish by asking you a few questions about the state of the music today. What do you think about the way music is mastered much louder than when you first started?

Well because of the advent of the digital age now technology makes it a little bit different. To me it all boils down the quality of what the engineer brings to the table. At the end of the day, what you hear is what the engineer is bringing to the table. That’s why I used the best mixing engineers for my products. I can make the best song but if the engineer doesn’t do a proper job in enhancing the quality of the instruments around the song you will say this song is an inferior song. I always endeavour to use quality musicians and a quality engineer.

So what you’re saying is it doesn’t matter how loud it’s mastered because if you’ve got the right engineer it’s going to sound good?

Yes, once it’s mixed properly the mastering is another process of enhancing what the engineer gave you. As the producer I give the engineer a project, he enhances it, I take it to the mastering room and they enhance it further.

Romain Virgo and Christopher Martin are both products of Digicel Rising Stars. Why is it that Jamaican TV talent shows produce real talent unlike in UK where winners are soon forgotten?

Ah. I don’t know how to answer that question. OK, I found Romain Virgo after he won that competition. Now I have Shuga and Dalton Harris who won the same competition. I think maybe it’s the level of commitment from a producer that can also help to bring these people to the forefront. The trouble is that sometimes a person wins a competition and they feel they have conquered the world when it is just a few people in one part of the world that knows them. I always tell the winners that come here “Look here, only the people in Jamaica that watch TV know you, so don’t get carried away with it. You have some talent so let’s work on this talent to get the world to know you and appreciate what you can give them”.

As someone who was involved in radio from the early days in New York – what do you think of the reggae radio industry today?

(Laughs) Well I think for the last ten years the radio has been the demise of the music industry because they have been playing too much junk on the radio. Not professionally produced songs. Songs that are off key. Some atrocious recordings have been played on radio stations. They’ll play ten songs from one artist and probably of those ten songs there might be three good songs but because the artist is hot they are going to play those songs. And you might have a young artist who has a very good song that doesn’t get any exposure because they have come again with one artist with ten songs. So they help to contribute to people saying the music dying. The music wasn’t dying because people were making songs still, but they are just not being exposed. Payola is a big problem because the integrity of these shows is being compromised when you listen to it. Because some songs you just know “What on earth is this disc jockey doing playing this song? Why is it being played on the radio?” It’s a reality. You can’t get away from that.

There is more good music being played on Jamaican radio of late.

Yes! Definitely! There’s a new trend because there’s a new set of artists that have come up. The Chronixx, the Raging Fyah’s, my young set of artists Dalton, Shuga, D Major, who are committed to quality. I’ve heard enough people saying “the music is dying” to figure something must be wrong – let’s try and change the course of what’s happening with the music. For too long you could not hear a one drop reggae beat on the radio. It was only dancehall. How can you throw away the foundation of a music industry? If you build a house and you erode the foundation of the house it will make the house crumble. It’s the same with the music.

Your productions on this compilation have a timeless sound but they were still uptempo enough to be played in the dancehall. Is there too much of a divide these days between the sound of one drop and dancehall?

Yes there is. (laughs) The dancehall come very close to being calypso and then they moved from calypso to hip hop. They’re all over the place with dancehall. While reggae all you have to worry about the tempo and the quality of the melody and what we are doing with the production. I keep saying, even in 2014 Bob Marley is the biggest selling artist out there. What kind of work did he do? Reggae. So how can you throw the reggae? All the white groups in California and Europe. What are they playing? They’re playing reggae. You can’t throw the reggae.

You were involved in the Beres album that was up for a Grammy. What do you think of the reggae Grammy?

My take on it? I think the Grammy is just a matter of name recognition and nothing to do with the quality of an album. They recognise the name and they vote for that name. People from our industry really need to join the Record Association of America if they want to have an input on the outcome of the Grammy. If you want to get a vote you have to be part of the Academy.

But at the same time it seems as though Jamaican music is looking for validation from America. What about a Jamaican award show to rival the Grammy?

I say that all the time. That’s why I do not complain about the Grammy. Because I am saying “How can I be complaining about another persons’ award when I am not having an award from my industry?” I can’t complain about the Grammy! I can’t because we do not have a bona fide award show in Jamaica where people can have something that is credible and walk away feeling that they are rewarded for their work with a credible award.

Likewise these concerns over sales where everything is being measured by the Billboard chart.

Well, same situation. All these things are open to manipulation. So what I try to do – is I do not get caught up in all those things. I try to make a good song so someone can say “Mr Germain, I appreciate that song. I love that song you did. It made my day. It contributed to my day being a more pleasant day” and I am happy. I can see a young person that comes into the studio with nothing and I can see them end up having a whole career, a nice house, a nice car, a nice family - those are the satisfying things to me.

PHOTO BY STEVE JAMES