Blaiz Fayah ADD

Blaiz Fayah - The 'Shatta Ting' Interview

02/27/2025 by Steve Topple

One of France’s biggest exports who has defined himself with one of Martinique’s biggest music genres is back with a brand-new album. Blaiz Fayah is arguably the king of the Shatta sound, having released countless hit tracks across many years in the music industry. The sound – almost like old skool Dancehall – has compelled audiences across the planet and given Fayah recognisable hits on every continent. Now, he is back with another album, Shatta Ting, and Reggaeville was pleased to catch up with him to discuss the album, the industry, where it all started for him, and more.

Blaiz Fayah – thank you so much for talking to Reggaeville today, it’s great to meet you!

Likewise, thanks for having me!

So, we must talk about Shatta Ting. It’s your brand-new album, 17 tracks. Out on Friday, just gone. It's a great album – but we'll get into that later. But I'm interested because you release music quickly. Because you only released Mad Ting 3 in 2023. And suddenly you're back with this huge album of 17 tracks, loads of different producers. How long did it take you to put this album together?

I've been working on this album for about a year and a half. I started this project in Martinique. We made a writing camp with DJ Glad - everybody for one week. And then I just kept like half of the songs. And then after that, I went to Spain for another writing camp, and we made some more songs. Then I went to the Netherlands to have the gold plate for the song Bad. And then in the studio, we made the song with Tribal Kush.

So, it's like, I'm in my studio in Paris. I make songs. The thing is like me, this is my job and my passion. Every morning, I go to the studio and I just make songs. You feel me? I don't feel like I have limits or don’t have the time to create. Like I need to create, I need to make songs. Because I like that, I have fun making it. So, for me, it's something normal. And if I make songs, I need to release them. Because we can make like 100 songs and keep them into the laptop and nothing happens. Nowadays, if you don't drop songs then you can disappear quick.

I love this life. I love doing music. I live with the music. So, I must keep my fire burning, if we can say that, you know. But there is a strategy on this album. It's released like a single, because nowadays nobody cares about album, I must be honest with that. I can see the difference of numbers, like from a single off the album with a video compared to a song from the album, only from the album. When the album drops, then the difference is huge. So that's why it's important to release a lot of singles. And then on the album, there is a few songs that the people don't really know. But they know half of the album at least.

It's interesting you say that. When I interviewed Sizzla recently, he said in the past few years, music has changed so much that you can't just sit on music anymore. You must release it. Otherwise, as you say, you're irrelevant just like that - quickly. And, you know, that's Sizzla.

Yeah, but even Sizzla, how many albums he drops? How many songs on every one rhythm? Especially in Reggae and Dancehall, we used to listen to a lot of songs. And when there is nothing new, then it sounds weird. Because we used to have a lot of releases every week. Remember, like even 10 years, 15 years ago, everyone really like Reggae and Dancehall, they'd have two, three releases every week. So, every artist has like a lot of songs. And that's why I try to keep that education. Because for me, this is a kind of musical education in Dancehall and Reggae. It's different in Rap music or Rock and Roll.

But in Reggae and Dancehall, we used to release a lot of songs, a lot of songs, a lot of songs. Because some songs are going to the party, to some DJ mix, some songs are going to the radio, others on the sound system, sometimes only in Colombia, sometimes only in Switzerland. And that's why I drop so many songs.

Every song finds its own public. And sometimes it's different. I can have a big hit in Costa Rica, and nobody cares in Colombia. And a big hit in Chile, and nobody cares in Costa Rica. And a big hit in Seychelles, like a two-year-old song, and then I make this song in Paris, and nobody cares. That's why I still drop songs, and this thing motivates me. Because the world is so big, and I have the chance to see that. I know it's a big chance to see that.

So yeah, I'm like, just make music and have fun. And, to answer the question about releasing a lot of songs, it’s because I'm a bit afraid as well about hit songs. When I make a hit song, like for example Money Pull Up, making crazy streams, I must release another song after that. Because if I'm waiting too long, and the song after that is not working, then as an artist the confidence is getting low. And then if you release another song and it's not working, it's getting lower. And then after that, the way you're creating your music changes. You feel me? Because you are looking for the success and everything, and you are kind of afraid.

Do you feel that pressure to release then, the constant music? Is it a pressure on you to do that?

No, because to be honest nowadays I've got the label to deal with that. So, for me, I had the pressure on the last album, Mad Ting 3, because I had a deadline. I've learned about deadlines. It was the first time I was learning about deadlines. And this thing confused me a little bit. Because I was like, ‘Oh shit, I'm not ready. I don't really like the worst song I have. I can still deliver the project but there are some songs I don’t like! I need to think about it, but I don't really have time’.

So, I realised, oh shit, this thing is getting serious and professional, because I've never seen the difference before now. Before, when it wasn't working for myself 10 years ago, I was still doing music in my studio. But I didn't feel the pressure for this one. I've learned on Mad Ting 3, you know? And I didn't want to feel that again. So, I worked differently.

That's very, very interesting. And on Shatta Ting, you work with a lot of producers and a lot of them are from Martinique, aren't they? But there's Tribal Kush and other producers from elsewhere. Just talk me through some of the producers you've worked with on this album.

Most of them I’ve known for ages. There’s just one producer, Genius, I never met him in person. He just sent me a riddim and then I liked the vibe. It's After Party. But all the other producers, I know them since years and years now. And DJ Glad, Mafio House, I know them since like, I don't know, more than nine years, 10 years now. We used to work together before he was working for me. So, when I see now their name on my new album, making streams, and getting views, it's like, I'm proud of that. And I never changed the people that I used to work with. Because for me, we created the colour together. And if I'm here, it's because the riddims are cool, too.

We're a kind of team. And the success tastes better, the taste is better when we work together. It’s a family album, you know? It's not only about business, everything clean about business, of course, but it's more about that we're just making music, having fun like before. And it's just now people listen to us. So that's cool.

You've done an excellent job across the album, obviously the production is brilliant. The compositions are great, but the mix and mastering are also really good quality. Who did that for you on this album? Because it's perfect. It's really strong.

It's me.

It's you? See, I didn't have that information. It's really good.

Really?

Yeah, it's brilliant.

I was like at the beginning, or maybe you know, so you just want to bring me the smile for the day. That's cool.

No, I really didn't know. The quality is excellent. You live and breathe the shatta sound, don't you? But you've done an excellent job, especially with the mastering, of getting the balances right between making sure it's bass heavy, but that the listener can still hear kind of the instrumental detail. Propaganda, that's a really good example. You've got that Shatta sound still going on with the hard bass. It's quite electronic. But then you have brought in this Jazzy but Funky Soul sax.

Yeah, my father is playing the saxophone on this one. He was the saxophonist for a big, big artist in France. And he worked with Kassav', the group from Martinique, during like years and years. And so, I was like, yeah, on this one, we need to work together on this project. So that's why I wanted to do something. And then we went to the studio, and we were making the riddim. So, we built that song together, you know, it was pretty cool. And I kind of like the jazzy touch, you know, on this one.

But my techniques for mix and master is like I do the mix and master on the same session. When I mix the song, then I start with the drum, then the bass, then voice. And then I start bringing my master plugins, and then I can see what is going on, like high frequency, because when you put limiters on everything, the high frequency is going up. And then after that, I put everything in about music, you know, imagine everything.

Nowadays, a lot of mastering is too compressed. Like for me, I need to breathe, you know? So, I try to find the problem, if I have a problem in my mix, and then boom, my result is often cool. But the problem I had, it was for, because some songs are different. For example, Ghetto Whine and Propaganda sound completely different. You know, like the voices are not on the same level. I try to make the balance between every song. I struggle a little bit, but if you say it’s cool then yeah, this is my technique, I make everything in one session.

So, I find that interesting because nine times out of 10, most of the time on albums, someone different does the mix and someone different does the master, as you know, but the fact you've done them both and done them together might be why it's so slick, because you're in control of both elements.

Yeah, and the problem is there is too much ego problem when you deal with engineering. You, the artist, want it like that and then they change stuff because they feel they can change stuff. But I don't want it like that.

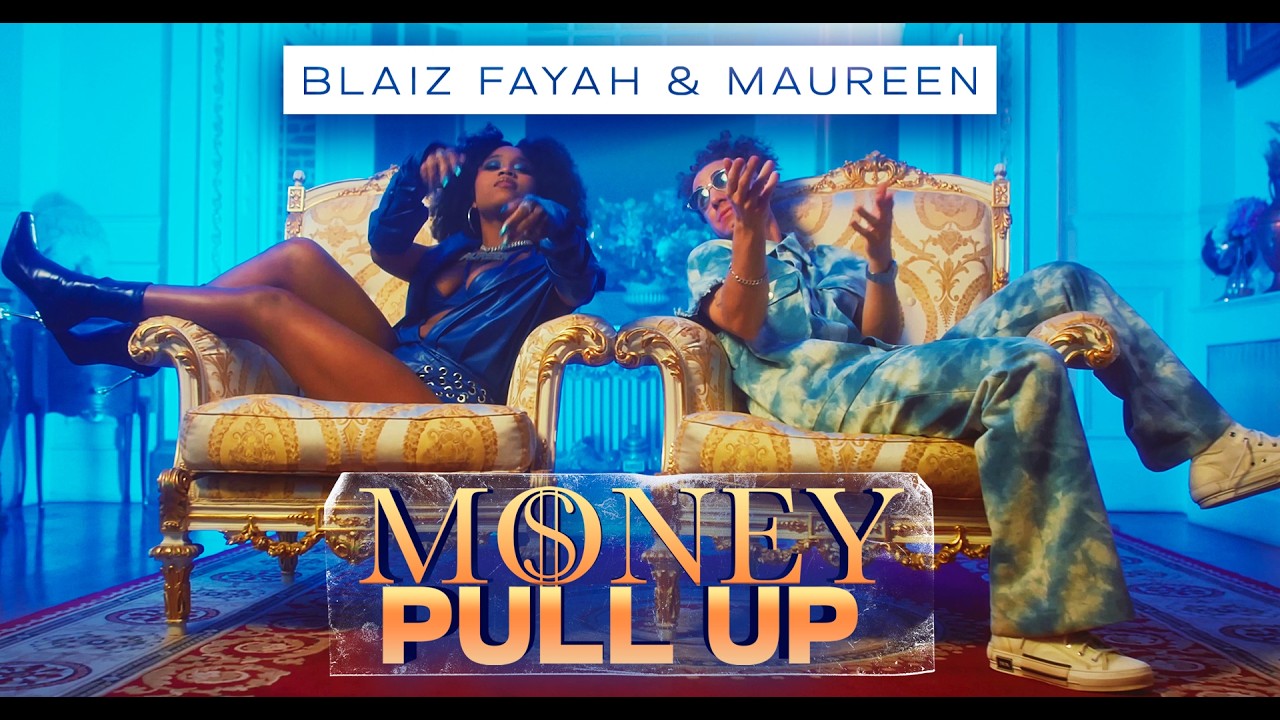

You've got a couple of collaborations on the album, one of them is obviously the track with Maureen which blew up crazy. She's a big artist in Martinique as well isn't she?

Yeah, she's a big artist in Martinique and France, and it was the right time to make this collab. First, the song we wanted to make was on another riddim. So, we made it and then I was like, 'No I don't really feel it let's do another one from scratch.' I had this riddim from DJ Glad, we made this together when I was in Martinique. So, with Maureen we choose this riddim and then we do this fast, fast - you know, I wanted a collab with a real collab vibe like kind of I’ll do one sentence, she’ll do one sentence - I didn't want like one verse then one verse then one hook then… you know like too separated on the song.

So, then we build that song and that's where we're just her and I in the studio. Then Mafio House make the arrangement of the riddim because it was sounding like a demo at that point…! But at that point the label was saying ‘Yeah we don't know about that song’ because it was an old school riddim like a Gaza track with the strings and everything.

Everybody was saying yeah maybe with Maureen you can make something easier, more accessible. But it was like ‘Yeah but if we do that like then we have nothing special’. So we kept it and then boom the song was released we have like between eight and 10k a day during one month and now, like we’re around 500k on Spotify every day. It’s crazy I never had that kind of numbers even with the song Bad made like gold in the Netherlands. But Money Pull Up got like more than 120 million views on YouTube. That's crazy for this kind of this type of music. It got crazy on TikTok and in USA, Turkey, everywhere – Poland, like a lot of countries.

It's a great track and you were right to force the label to do what you wanted because it's blown up

But interestingly, we put money on the video - the video cost around $10k or something like that. I was insisting, because I’ve known Maureen since years and years, you know, so I was like yeah for the first collab we have to put money on it. We need to show her that if you invite someone then you give some respect. I don't think she had a song like making those kinds of numbers since the beginning of her career. So, I'm quite proud. I don't think I'm going to make another song bigger than this one because like for this kind of music this is really huge numbers.

I'm going to be really honest, I didn't know much about Shatta before I had this interview lined up. But from what I’ve learned, unlike Dancehall, the Shatta sound hasn’t changed much over the years.

About 10 years ago all the Martinique producers had problems, because artists were producing tracks really slowly and that's why they were starting to put a remix on every riddim and that became Shatta – like, take off the kick, only have bass to have more space, sometimes they put the chords sometimes they put just the snare, sometimes they put other percussion. But the main thing is the bassline, vocals, and the snare. But it's minimalist - it reminds of the old school riddims from Jamaica. It sounds like something that they used to make but they completely forgot nowadays. But Martinique brings their own touch like because they have like a high bpm and it's the bassline. It's still dancehall but Martinique created their own vibe. Now, it’s started going up and up and up and then the Netherlands bring their own kind of vibe from Shatta, now Germany made it as well. But in Martinique it has to sound a little bit dirty - if it's too clean you know we're losing something.

I guess if it's too clean then it's not authentic. It's like the Will Smith of Dancehall, yes?

[Laughs] Exactly. We have to feel something nasty you know. But that's why there is a big bass because even if it's too clean you have a big bass, we still distort it a little bit. We have our own market with Shatta now because Jamaica seems to have stopped making like dancing songs. Maybe I'm wrong, but what I see like from five six years there is no more big Dancehall hits from Jamaica, and I think that that's why Shatta is going up and up and up.

I agree with you about Dancehall generally, it's kind of on the down at the minute and it's been replaced by Afrobeats. Artists were maybe making Dancehall too complicated: fusing it with firstly EDM, then Afrobeats to make the AfroDancehall sound, and now it’s heavily influenced by Trap.

There is too much technique, too much lyrics - it's too complicated. I like a lot of songs, but I can't put that in a party. It's too complicated, too dark, and too emotional. People have too much problem in their life on TV on radio and when they want to listen music, they want to listen something fresh that will take them away.

Yeah, that's what Reggae is for…! That's what's struck me about your album but also the Shatta sound more broadly. It feels really modern, but it has got that old school kind of feeling where you just want to bruk out – y’know?

Yeah exactly, we just want to have fun. I was running this morning and I was listening to a mix from DJ Fearless with all the brand new songs from Jamaica, and I was like, you just want to kill someone after 20 minutes you know what I mean? You're like ‘yeah bro I just want to grab a gun and shoot two time’. I think even for the brain of the people it's not good to listen to that kind of songs every day all day long because it changes your mindset.

When I was in Jamaica, I made a song with this new artist and I was explaining him, because he's really young, and I was like bro if you want to have career look at artists like Busy Signal: they're traveling from years and years and years in Europe and all around the world. Why? Because they have hits and proper hits for everybody. You have hits now but it's too violent. It’s crazy that I have to explain this to the new generation like there is like something broke there you know like between generation there is something completely different. It's like the new generations are more influenced by the USA. For example, the smoking of cigarettes - like the new generation smoke cigarette – not the herb and grabba.

I mean it's sad at the same time because Jamaica for me has influenced the world since decades and decades and decades and now is like we have to bring this explanation to them then they can understand. With Shatta, with Martinique, what we're making, what we're bringing to the world is a good thing because you can dance on it.

As I said earlier on in our conversation there's not that much information out there about you online. You mentioned your dad is a musician as well and plays the saxophone. Just tell me a bit about how you started in music and how you got into doing this as a career.

I started music around five years old. I was doing piano because in my family we must make music, like we're musicians since three, four generations. My grandparents were doing music for a French orchestra - classical music - and my grandmother was a flute teacher in Paris. Then my father started with the flute and then saxophone, and then he built his own studio really quick. Then, a studio was a good business because nowadays a bit hard. So, I'm born nearly with a studio in my house! He was working all the time, producing stuff doing music, so all my life I've been eating with the music you know - because we have the house because of the music, and you feed all the family because of the music.

When I was older, I started with kind of Rap music with some friends, writing, trying to discover and to learn how to record the voice and how it sounds different in the microphone than in the real life. But I was young and after that I changed from Rap to Reggae. But I was so weak – like, really weak. Honestly, it was really bad! And then after that I went to London and then I switched from performing in French to English there. My manager was Jamaican then. I used to give him a listen about my song and he was making some corrections - and I thought, OK I'm getting better and better and better it's not that good but I'm still doing it better than before…! I was trying to be like Buju Banton, Sizzla, Red Rat - but I never really had it. After that I said I can't go higher than that I can’t go lower than that. So, I discovered myself first and then moved to Shatta.

I made this song called The Police and it was the first hit then me and Mafio House have. It was a hit in in Colombia. Then after that I made Best Girl and all those kinds of song was eight years ago, I think. I've worked a lot to get to know me, but I was frustrated during years and years. I was like why I don't have ‘that thing’. I felt like it was not good what I was doing – and eventually, it happened.

I'm consistent as fuck, you know? Consistency is the key. I release between eight and twelve songs every year, sometimes more because there is some collabs. There are at least eight videos every year, there is a lot of shows - because if I miss the train then it's done. So yeah, I grew up in this kind of musical thing, but it gave me that work mindset as well because I saw my father work a lot, my grandfather, grandmother work a lot - and I was like okay that's a real job.

You have had some huge numbers on streaming and social media and yet there doesn't seem to be much interest in you or the Shatta sound from the broader music industry or music journalism. Why do you think that is?

Sometimes I think about it and I'm like they're gonna talk about one guy who’s been to Colombia to make one show I was like yo, I've been to Colombia look and they put up one article on this guy who has been to Colombia once. I've been five times to Colombia, five times to Costa Rica, two times to Chile, and Mexico and I was sometimes a little bit frustrated. But the positive point is my public, the crowd, following me since years and years now and they make me big without articles - and it's getting bigger because I had all this before like without media – and now media starts taking interest because music talks and numbers talk.

At the beginning I was like a bit… not hurt, but I was like that's weird you know. But nowadays everybody gives me my respect: every artist from the game, every producer, every label - but it's more about media. I don't think there is a problem, but the other thing is I don't really show my face, my life, my stuff, you know - my private life and everything. Maybe it's something they don't like – but my music talks now; the numbers talk and because my music worked more than my face and more than my name at the beginning, I think that's why it took time. I was dropping a lot of songs, but a lot of people didn't know my name, so it created this kind of problem. But at the same time was cool because nobody recognised me because I'm not under that fame stuff.

For me it's a bit annoying and as you say like there is not that many articles, but it has started going - like yesterday I was with Billboard USA in an interview. So, it's like a big thing for me, and it's like a kind of motivation as well to be honest. I'm like ‘Oh you don't want to talk? Okay let's make songs’. I live life for me and for the family and for the team I work with. I don't live life for the media because I know some people look for some buzz and stuff but I’m not on that kind of vibe. If they don't want to talk then they don't talk.

I think if I was singing in French, it was it would be easier to get media attention here and even Martinique. But the way I've chosen another language maybe put a kind of barrier, I think. But my songs couldn't reach every country if I didn't, and I'm happy with because when you go to Costa Rica, Chile for example last summer like everybody's been crazy. So, for me it's not a bad thing but one day they're gonna talk about me, maybe, I hope.

I think so! Just to finish up, the album's out now and you're touring as well, aren't you? You're touring throughout March across France?

Yeah, across France so we started on Thursday 27 February across France and then we finish with Dortmund, I think - like Luxembourg and Dortmund. And then we go back to Costa Rica the 31st of May, and then we have a Europe tour for festivals in summer and we go to Canada for three shows there so yeah - it's cool. Maybe we go back to Seychelles and Mauritius – the Indian Ocean.

It's been amazing chatting with you Blaiz. Thanks so much for your time and big up from the Reggaeville team!

Respect – big up yourselves!