Bob Andy ADD

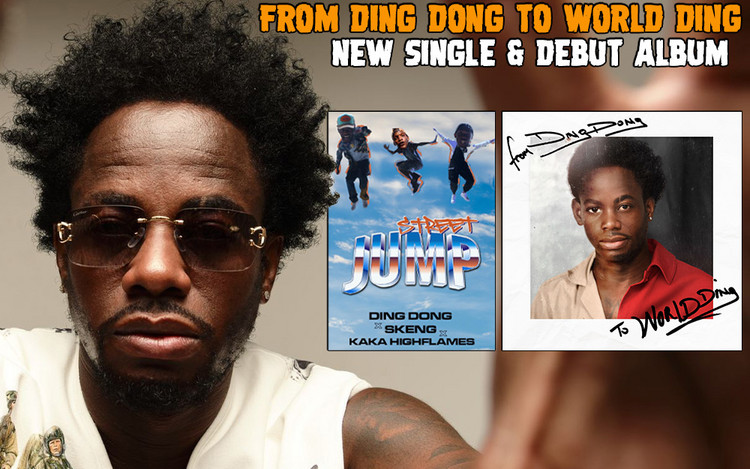

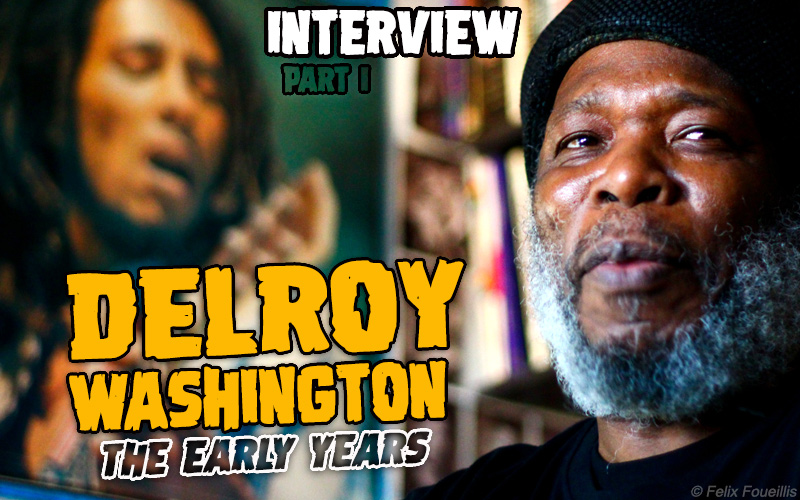

Delroy Washington Interview (2012) Part I - The Early Years

05/04/2020 by Angus Taylor

The passing of Delroy Washington from coronavirus on March 27th, 2020 robbed reggae music of one of its most distinctive and original singer-songwriters. It also removed, from an already crowded and competitive field, one of reggae’s biggest characters.

The Jamaican-born, London-based artist was known mainly for his two critically-acclaimed albums I Sus (1976) and Rasta (1977) on Virgin Records, and for his friendship with Bob Marley. But this only tells half the story. For as anyone on the London reggae scene will know, Delroy spent the decades after the 70s as a community activist and mentor to young people in his home borough of Brent.

Born in 1952 in Westmoreland, Jamaica, Delroy Washington relocated to London at the start of the 1960s. Regular sound system parties held by his uncles, and encouragement from his school music teacher led to him singing in soul and reggae bands.

Always at the heart of the action, Delroy was soon moving with Bob Andy and the Pioneers, for whom he recorded backing vocals. A chance meeting with Bob Marley sparked a close friendship when the Wailers were living in North West London. Delroy would contribute to - and claims to have helped write songs for - the Catch A Fire and Natty Dread albums. He would also be a key figure in the rise of another progressive reggae group, Aswad.

The mainstream interest in Bob’s wake, and Delroy’s own visionary singing and songwriting abilities, resulted in a record deal with Virgin. The two albums he cut for them are prized examples of the complex and cosmopolitan songcraft that defined “progessive” reggae music in London.

Although he never achieved international success again after leaving Virgin, on a local level Delroy was seldom out of the picture. He headed up the British arm of the Federation of Reggae Music and was involved in the UK Twelve Tribes of Israel. In the late 80s and 90s he was part of the team behind the One Love concerts in West London, and his mentoring programmes helped a variety of young talent, including Gappy Ranks. More recently, he sat on the Harlesden Working Group for the London Borough of Culture, whose No Bass Like Home 2020 project celebrates Brent’s musical legacy.

This four-part interview with Delroy is the result of 5 hours of audio, recorded on the phone and in person, in 2012. That year, Delroy had been left out of Kevin MacDonald’s film Marley, and, due to deadlines in relation to Delroy’s community projects, it was decided that only a small section on himself and Bob be published in United Reggae magazine. The remainder of the transcript has never been seen before.

Angus Taylor sat down with Delroy at his cluttered, historical treasure horde of a home in Harlesden. They were joined by an old friend and longtime fan Frank Payne, who interjected with the names of various contacts Delroy met on his adventures. At the time, Delroy was driving a successful initiative to affix blue plaques at the North West London dwelling places of reggae figures such as Bob Marley, Dennis Brown and the Cimarons. He was planning to write a book about these encounters - which sadly was never issued. This interview serves as a partial document, not just of Delroy’s life but also the cultural impact of, arguably, the centre of foundation Jamaican music in the UK.

Anyone who knew Delroy knows he loved to talk. And he held forth for an entire afternoon on his history: growing up with Peter Tosh, helping Bob Marley to make his lyrics sound less Jamaican, and how his experiences of racism, art college, Rastafari, Buddhism and martial arts shaped the man he became over the years.

The conversation went off on some marathon tangents and important parts of his time-line were missed. There is not enough discussion of his early reggae singles, or the business side of his dealings with Virgin. His opinions are those of 2012 - and may well have changed in the eight years that followed. But instead of being a pure narrative, the below text is a showcase of Delroy's holistic theories of music, philosophy, life, and how it all connects. His story is as much the story of the many names he pulls into it; the ever-changing cast of characters who made their industry happen.

Like fellow UK reggae trailblazers such as Dennis Bovell, Black Steel and Tan Tan Thornton, Delroy’s taste in music and culture was incredibly diverse. These myriad influences, amid the rich counterculture and political turmoil of the 60s and 70s, informed his songwriting to diverge from popular sound system trends in his new home.

There was an openness and a lack of pretence about Delroy. He thought expansively and would talk to - and include - anyone who shared his vision. He always had multiple simultaneous projects on the go. There were occasions where these qualities may have held him back in the ruthless, single-minded music business. Yet they also provided a fascinating window into a reggae artist's life during such an eventful time.

There have been many moving tributes to Delroy Washington in the last few weeks. This is a celebration of his life in his own words. Part I concerns his early years as a Jamaican adjusting to London. It includes his memories of another recently departed singer, Bob Andy, who first encouraged him to record.

Delroy’s family are currently trying raise funds for his funeral costs - you can donate @ GOFUNDME.com

Where were you born in Jamaica?

I was born in a place called Westmoreland in Jamaica. To be more precise I was told I was born in Savanna-la-Mar but in Jamaica we all call it “Sav la Mar”. I grew up around a place called Peggy Barry. In fact, my aunt Ruby in Swindon, a very articulate person, told me the place where I grew up was called Burnettville. My grandfather and his family owned the whole place where we lived. Most of my family were people of means. I grew up seeing my family having things like land. My grandfather owned two shops where local people would buy stuff like groceries. But he was also a preacher - or a minister as people call them now.

Which denomination of church?

I think it was Baptist. He was a Jamaican Baptist Preacher. But the funny thing about my family is they all had churches! My grand uncles all had churches. So I literally grew up in a church. It was like literally learning to read out of the Bible.

What was your first musical experience - was it in church?

My experience of music was that I was always singing! I've always known myself to be singing. My aunt Reenie said I was singing before I could talk. I can always remember myself singing going through the cane piece. I remember standing up on these Pepsi Cola boxes to sing. Pepsi was quite a popular drink back in the day at one point. Everybody preferred Pepsi-Cola to Coke in Jamaica. I think I was about 5 years old. They used to put me on those little boxes to sing and they used to give me money so I thought “Yep, singing for me!” (laughs)

But my first real experience was doing a concert in church. I think I got cold feet when I saw the amount of people that were there. It wasn't until they were ready to come and take me off that I started to sing! (laughs) I must have been about 5 or 6. I just couldn't believe there were so many people in the audience. I don't think I was frightened, I think I was just looking at who was there. Who I could recognise and who I could see. But I did pull it off eventually...

Was there anyone you grew up around, artist-wise, who is known now?

Yeah, Peter Tosh. One of my uncles who we called Man Man, his name was Winston and Peter's name was Winston also. So the two of them were the two Winstons and they were like really bosom brethren. Peter used to literally live in my grandfather's house down in Grange Hill. So Peter was the first person that I would have known and then Bob Andy also used to live in the same little area. I think the Jays as well.

What was Peter Tosh like as a youth?

Really nice. He was like an uncle or a bigger brother really. Nice person. I would say Peter was golden. That wasn't the Peter that people later came to know. Peter for me was a nice person who used to take me to school in the morning on his bicycle. I used to go to a school called Cashew Walk School and Peter and uncle Man Man used to go to a school called Mannings High School. So never let it be said that Peter wasn't educated because he was. But eventually he went off to Kingston and I would bump into him again in Kingston when we were staying in Trenchtown with an aunt of ours called Miss Clarke. That's where I used to live, down at West Street in Trench Town when I went there.

Was Peter influenced by Rasta before he went to Kingston?

I can't say because Rasta was not the thing that people did! (laughs) I know that as a child I used to be attracted to the green, gold and red colours. These kids at school had these little buckle belts that always had green, gold and red. I would always tell my grandfather that I wanted one and he would say “No! Cyaan get one of them!” I have another brother who is pretty much the same age as me with a different mother. He was interested [in Rasta] from ever since I can remember. He was probably my very first influence - my brother Sedley. He was always running away to Rasta camp and we would always wonder what was wrong with him! Because Westmoreland has probably got one of the biggest Rasta communities in Jamaica. And obviously down at Orange Hill is where they grow the best sensimilla.

So tell me a bit about your experiences in Trenchtown.

It was while we were trying to come to England that I ended up in Trenchtown. We always had to go back and forth to get our papers in Kingston, that's what people did. I think the journeys were just too much for me so I ended up staying there for a little while. I was going back and forth but I was there most of the time. I kind of liked it because one of my cousins, Lloydie Clarke who became a singer as well back in the days, was a big influence on me as well. So I basically ended up staying there because I was trying to get my papers to come to England. Eventually we got our papers and my dad came from Kingston to England.

What I can remember about Trenchtown was the youths were very ingenious. Because we used to make some things called “skate”. When I came to England I saw that they had a similar thing but they were called scooters. But we called them “skate” in Trenchtown. That was my thing, riding on skates. That is my lasting impression about Trenchtown.

How did they make them?

They used to make them with a piece of wood that formed the body of the skate and then you had ball bearings for the wheels. Very simple to put together. And bicycle racing down the road. I remember the kids riding backwards on their bicycles. I thought it was a big thing to ride a bike and they were riding it backwards and I thought "How do they do that?” And people were into their music. I remember every Saturday night they would talk about going to Duke Reid and Coxsone. I remember them talking about their crinoline dresses. Getting their “Crino” to go to the dance. I remember those musical things happening around Trenchtown. It was quite vibrant as far as I can remember.

Why did your family want to go to England?

Some of them were over here already. I was having problems because I must have missed my mum and my aunt. I grew up with them and they were all over here. As a matter of fact some of my family went to America. My uncles went to America before they came to England. It was like everybody seemed to be coming to England and they thought I was quite bright and my aunt was saying that it would be good to come over here to get education. So that was primarily about the education thing. Because they said they had better education and opportunities over here. I came here about 1961. I was quite young at the time. Maybe about 8, 9 or 10.

How did you find London? What is your memory of what it was like when you first arrived?

When I came to London I remember we were coming from the airport and I thought it was going to almost look like Jamaica. I remember I came into Paddington and I thought the houses didn't look right! (laughs) I didn't even know that they were houses to be quite honest because even in Trenchtown the houses were ok at that time. My grandfather's house that I grew up in was a proper house with books, electricity and everything. We had all the mods and cons people at that level could afford. It wasn't like my grandfather was a really rich person but he wasn't badly off. So I had a nice room in my grandfather's house and then I came to England and I thought “Is this it?” And it wasn't that I was being rude or anything like that but I wanted to go back home!

What was it that made you want to go back? That it was very grey? These Victorian terraced houses all in a row?

Yeah it was grey. It wasn't nice at all. Although I came here in the summer. I think it was August so it wasn't that bad. I remember going round some places and eventually I got settled into it. When I came to England, I don't know what it was, but it just was not what I expected. I wanted to go back to grandfather. I remember really and truly telling them that I didn't want to stay here that long. Because I've always been a bit conscious of things and I always used to speak my mind.

But it was a long stay man. And to me it was like being in prison. That was the first thing I learnt about England. Where I was free to roam about in Jamaica, it was like I couldn't go anywhere here. I always felt like I was stuck in the house. Apart from I made friends with these two white kids. I think they were called Michael and Ian Ritchie. They used to live a couple of doors away from me, nice kids, so I used to play with them. I knew how to play cricket because it was what people did in the Caribbean in those times but I didn't really know about football too much.

The only thing I did like about England was television. I liked television because it had music on. I remember Cliff Richard. People will not believe it but that is how me and Johnny Rotten became friends. Because he and I like music and we had a similar taste. Because I knew something about music, he and I hit it off.

Which TV shows did you watch?

Saturday Night At The London Palladium. I used to like all the pop programmes. Ready Steady Go was the big programme at the time before Top Of The Pops. Then Top Of The Pops came in and I liked Top Of The Pops! Anything to do with music on television. Trust me, all the pop acts from the 60s I can tell you all about them because I was a pop music fan.

When I was kid I loved The Beatles. I loved the Kinks. I could tell you all about Waterloo Sunset and Dead End Street. I'm not going to hide it because I want to pander to some people's sentiments. Black music was always in my house. People like Dinah Washington and Brook Benton. But the funny thing is there were people like the Yardbirds in my house. People say “What do you know about the Yardbirds?” and I say “They had this song called For Your Love which was a big tune in the black community”. Maybe some people might not understand that some of the older black people used to have pop music as well. My aunt used to love Mick Jagger. She was one of the most prudent people and she just liked Mick Jagger. She thought Mick Jagger was comical. How he used to dance.

As a little kid I used to love listening to Elvis Presley because he was like Michael Jackson back in the day. If there was no racism we wouldn't have had some of the problems that were associated with Elvis.

Where did you first live?

We lived in Paddington. I lived with my aunt. My dad went to live somewhere else because it was very difficult to find housing at the time. He lived with my uncle down in Kensal Green. I lived at Fernhead Road in Paddington. Eventually after another year or so so we moved to Harlesden. I remember they bought a house because we were always keeping dances. They had a sound system and I think people who kept dances saved up their money and bought a house.

I'm always telling people about this white Jewish man. He was like my Uncle Mike. Uncle Mike played a very important part of my life. It was Uncle Mike who taught me to speak English. He got these encyclopaedias and I remember him really getting behind me in music. He was always giving us little things to help me along. He was very helpful to my family and I think it was him that helped them get the house back in the day.

How did your family know him?

(laughs) I can't say! I think he used to sell insurance or he used to sell things anyway. I think because my uncle-in-law was into music and Mike was into music they had that commonality. And Uncle Mike was a very helpful person to my family. Because even when we moved out of Harlesden and went to Kingsbury he was always still around us.

What was your first experience of racism in London?

My first experience of racism happened here in Harlesden. Paddington seemed to be more integrated. The kids tended to get on together - the black kids, white kids and everybody we all seemed to get on alright. Harlesden was where I had my first experience of racism, going to Oldfield Road School, being confronted by some white kids in a playground and their dogs. There was a kid called Philip Roach and his youths them, his brethren. Backed me up against this wall and it was a brethren, a black kid called Lloydie Walker that came and saved me. And Lloydie Walker and I ended up being really tight because they lived around Dalmeyer Road and Church Road and I lived at Brownlow Road.

That was my first experience and then having running battles with them in the evening. I remember making what they used to call a catapult, like a slingshot. I used to hide my slingshot round by Curzon Crescent and make sure I had some stones. I was really good with my slingshot because I used to shoot birds in Jamaica. Every evening I raced around there. It was like a nightmare situation. Every evening I got scared and wanted to go home and those kids were always on my case. So I used to fling stones after them and they got really mad when I started using my slingshot. I started a craze where I started making slingshots and selling them to other little black kids around the area. That was before guns came in!

But funnily enough, I was befriended by a little white kid called Lesley Salter who kind of changed my whole attitude. Because some of the white kids were ok but the kids that had the problem were the kids that lived in the council houses. Lesley lived up the top of my street. Near Church Road Post Office. It was Lesley that taught me to play football, billiards and snooker because I think his father was a snooker champion. So I moved with Lesley and became really tight. He was a Man United supporter. I remember this always.

How old were you then?

This was when I was about 11 or 12. I remember Lesley's mum, a really nice white lady, persuaded my aunt not to send me to Pound Lane school because “as far as we were concerned it was the pits”. And Gibbons Road School which was round the corner - “a lot of bad, really rude kids go to that school!” So she got me to go to John Kelly school in Neasden and that was like another experience. For me going to John Kelly was the business. Trust me, it was a nice modern school, a nice environment.

John Kelly had this really good music teacher. I never forgot him as long as I live. His name was Mr Fordham. Another Jewish man. He put me in the school choir. He said to me “Come and sing” and he would look at me and say “You're quite good”. Mr Fordham kind of took me under his wing and started to teach me all kinds of things. His thing was classical music so it was from Mr Fordham that I learnt about classical music. Even during lunchtime he was always in the music room. I used to go in there and sit down with him and we used to listen to Holst’s The Planets Suite and Peter And The Wolf. He was very good at explaining how the things were moving.

And he encouraged us to play pop music which was really odd for a classical music teacher. That was where all the bands started from in our school. In the music class. I wasn't in the bands initially. I was a singer. But we had some really good musicians coming out of our school. There was one guy who eventually ended up being the leader for the Philharmonic Orchestra or something like that.

John Kelly had some really good reggae musicians. Junior English went to John Kelly and some of the others like the Dawkins’. George Dawkins was someone who as soon as school finished had to go home and get his music lessons. He could play trumpet, he could play the flugelhorn, the saxophone. He was into all the wind instruments. But eventually he taught himself to play bass and all those other things as well. So George was a very outstanding young musician around us. And then the bands started. My brethren Mario Grant got his guitar, the Beckford family - who I think I'm related to! - I remember all the guys started their little bands. And there was one Pakistani guy whose name was Parvez Kayani, a good boxer as well.

Because the other thing I was into at school was sport. I was on most of the sports teams. I was on the cricket team, I was on the football team, played table tennis and then basketball became my thing. I fell in love with basketball and learned to play by watching 8-mm movies. They had an 8-mm [projector] so I used to get all the films with my pocket money and show them at lunchtime.

Most people that went to school with me will tell you a very strange thing about me at John Kelly school. I was a little kid that had a key. Keys to the gym, I had keys to the art room, Mr Fordham left me his key to the music room. Even the geography room at the top of the school where I used to show the basketball films. It was kind of funny because the teachers trusted me. I wasn't the head kid but I was pretty reliable when it came to athletics and stuff. I even had keys to the store rooms. Even the dinner ladies! They all liked me for some strange reason. (laughs) Because I learnt a thing about making myself useful. So people eventually trusted me with stuff. I always ended up getting more lunch at school than all the other kids!

Which other subjects did you enjoy at school?

Art and English. Those were always my two top subjects. History as well and then Technical Drawing, I was quite good at that. I got GCEs and A-levels in some of those subjects.

How did sound system figure in your teens?

Sound system started way before my teens because of my uncle-in-law and his brother. Daddy Ernie’s uncle was my uncle-in-law. And they had two sound systems. I don't want to tell you what the names of the sound systems are because I feel embarrassed that two black people had two sound systems called Tarzan! Tarzan The Invincible they were called! Number 1 and number 2. But they were big sounds back in the day here. Ernie's dad was one of the big sound system owners around here and he was a builder and had his own company. He was one of those black people who was really quite independent because when I came to England, if you had a house as a black person you had to have a really decent job. His dad had a house and I think they had another house that they rented out.

So I grew up around sound systems over here. I knew people like Duke Vin and Count Clarence - all the sound system men. Chris Blackwell used to sell those records too so I knew Chris Blackwell. I knew him from way back in the days when my uncle Duncan used to cut dubplates or what they used to call “wax” at this place up at Cambridge Gardens. The man that is known as Orbitone today - Sonny Roberts - used to run that place. So I was around that whole scene from when I came to England.

I can tell you about all the sound men that were around at that time. Because my people knew most of them. Duke Vin was the main man, you had Count Suckle, you had Count Clarence and you had Lenny The Lion, who ended up living in one of our houses downstairs. So I grew up around the music. But pop music was also something that was going to have a major impact on my life.

By what route did you enter the music business?

It's kind of funny because I started off as an R&B singer. We moved from Harlesden to Kingsbury around 1966 or ’67. I had a friend called Wayne Francis who came from Grenada. Wayne was also a fairly radical youth. Wayne thought he was kind of my manager. He was into groups like the Temptations and Smokey Robinson and the Miracles and he had all the records. I was always around his house on Lavender Avenue because he had some different records from the ones I had in my house in Deanscroft. I used to like his sister as well! (laughs) She's my good friend still.

In fact there was a time when everybody thought that I came from “small island” as they used to say because I used to be moving around with all the Grenadians and the Bajan kids. I was one of those kids who did not have those hang-ups about “small island, big island” thing. I think it was because of how my grandfather grew me up. I didn't have problems with calling people names.

I started off with a group called the Mayfields. It was Wayne's group. Wayne put them together because he really loved Curtis Mayfield and we were all into the Impressions and Temptations and those groups.

So did you do a three-part harmony?

It was a five-piece group like the Temptations. But trust me we were good. I'm not joking. We used to go to a club called the Railway Club in Harrow. And I met up with the Pioneers and I told them that we had a group as well. I said “Do you want to hear us sing?” I was always kind of forward. So I met up with Luddy Pioneers. We went to his house over in Leytonstone one Sunday evening and I think they were quite impressed. They said they wanted us to come and open up for them on tour. It never happened because the rest of the man were never that serious! From when I got the bug I thought “This is something I could do”. Because as far as everybody was concerned I could sing.

So I started taking it more seriously. It was them that entered me into talent contests at the London Apollo club. And I always used to be winning! Hands down every week I won it. Everybody ‘round here can tell you that every week, every heat, I won right up to the finals. And there was an African brother called William Edozie, who was known as William Brown. He made some good records back in the day as well. William was really a good showman, trust me. He was like James Brown on stage. He could sing really well and could play the harmonica like nobody's business. But he always used to stay too long on stage. You were supposed to go on for 5 minutes and he thought he was doing a big show, so that was how I beat him! Because I just got up there, did what I did and came off. People had to go and take Willie off the stage!

He and I were friends from school because he went to John Kelly as well. He was in the same class as me. But trust me if everything had been a certain way William could have been one of the biggest artists in this country because he was a showman. And he looked the part as well. Everyday you saw him he was always dressed up like some American guy. He used to look like one of the Jacksons.

Do you remember writing your first song?

My first song that I ever wrote was a song that we did with Bob Andy. Because Bob Andy was the first Jamaican artist to take me to studio. Him and a guy called Joe Sinclair - who as his claim to fame used to work with The Police. He was the one that started helping them up the ladder. So Sting and I have something in common in that way.

I remember I always used to write poetry. Because we were encouraged by the teacher Mr Bailey to write poems. I really like to read a lot of Shakespeare. We did Lord of the blooming Flies. We did Greek mythology. I've always been reading madly ever since . So poetry was something kind of natural. William Wordsworth. We used to have a teacher called Mr Edwards at my junior school who used to be a Wordsworth specialist.

In fact what happened was I started out singing in an R&B group but I used to have these books that I used to write poetry in. I remember Bob commenting and asking if it was me that wrote all that stuff because I think I was writing some really funny kind of poetry! It was very surreal what I was writing.

That was how I got this deal at Trojan Records, well it was B&C that eventually signed me. But I remember Webster Shrowder, who used to be one of the directors of Trojan, saying to me “Delroy you should try and write some different kinds of things man” because I was writing some really radical stuff. Because I had the experience of going to art school as well. Being in that kind of environment and all this Vietnam war stuff was going on ‘round about 1969. A lot of kids that I was going to art school with were very up on some of this stuff.

Tell me a bit more about your experiences at art college...

I had a friend of mine called Keith Drewitt. It was really funny an artist having a name like Drewitt! But he was just absolutely brilliant from day one. I just knew he was gifted. He used to live down the road here as well in what is now Church End. Keith and another friend called Pratchett. They were well up on things because I remember Keith being into John Mayall. A really interesting musician. And he was into people like Cream and groups like that. He was into all the progressive stuff that was going on in London at the time. It was kind of funny that a white guy introduced me to people like John Mayall and through John Mayall I started getting into all the bluesy stuff.

And I was into acting as well. A lot of people don't know that. I did a lot of theatre acting when I was a kid. Around that environment there were a lot of people who were into some radical stuff. Jean Paul Satre and people like that. I remember sitting down and listening to all my big white acting friends talking about all these radical people. So I got into a situation where I started learning more about people like Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. But funnily enough when I buck up with Peter [Tosh] he was the one who was really into all these radical people. But Peter was not stupid. A lot of people think that Peter was just radical and he was really mad. He wasn't. He was a very brainy person. He knew quite a lot about a lot of stuff. He might not have talked about it ordinarily but he knew a lot.

Which studio did Bob Andy take you to?

A studio called Chalk Farm. Chalk Farm was where everybody went to. That's where most of the reggae recordings were done for Trojan Records. It was their main studio, [run by] a brother called Vic Keary. In Camden Town, near the Roundhouse. I was about 17 or 18.

So I did the stuff with Bob Andy. That was some R&B pop stuff because they thought that the songs I had written were good enough and were saying it was an international type sound. Joe Sinclair thought he had really found something seriously. And when I hear that song now I hear the same progression in a million and one songs nowadays. But they never released it. I did a version of it for Virgin Records but it never came out. It was called People. And Bob Andy sang on my song called We Used To Meet In The Morning. I don't know what happened to that song because when Bob sang I thought “Whoa. That was my song!” (laughs) I have to check Bob Andy about that because he really made that sound like a proper song.

What was your first released recording?

My first recording was when I used to do a lot of backing vocals stuff. I started moving with Pioneers, so one day Luddy Crooks took me to the studio to do some backing vocals. The first tune I actually did was called Long Island - singing backing vocals. It was on a Tony Brevett tune called I'm Sorry (released as So Ashamed). They thought the harmonies were so good that Mr Palmer released it with just the harmonies. I thought it was kind of weird because I could have done something to it. But they just liked the harmony so they released it as Long Island in about 1972.

But my first song that I was going to release was a song called Jah Man A Come, because by that time I was moving with the Wailers. That was me and Clem Bushay now. People talk all kinds of things but Clem Bushay was someone that I brought into the business. You know Clem Bushay?

Yeah, he recorded the first album by Tapper Zukie...

Right. Tapper Zukie, it was me that first took him to the studio. He will tell you that. Because Tapper Zukie used to be a bad boy back in the day. He got himself into some trouble and it was me that got him out of it and took him up to stay at my family's house in Kingsbury. He told me he did some deejaying and he would like to make a record. He started doing some deejaying stuff to me and I thought “Hold on a second, he don't sound like U Roy or Dennis Alcapone and he don't sound like Big Youth. He sounds like himself!”

Me and Clem found the studio called EFM up in Clerkenwell. Clem found the studio but I was the one that had all the links to the business. He can tell you all kinds but it was me that introduced him to Alton Ellis and me that introduced him to the Pioneers because I knew both of them. Clem used to drive the prettiest Capri in Harlesden - that's what we used to call him “Capri”. A red and blue Capri. He was a good looking guy as well so most of the girls liked him.

We got these records, American imports. This was me moving out of Pama records. I got these imports from this guy who used to bring them over, so I started going around selling these import records to different people. He told me that he liked music and by this time I'd been learning to play the guitar moving around Bob Marley and people so I started showing him a few chords. I learnt them not just from the Wailers, it was from a brother called Ranny Bop. You know Ranny Bop?

Yeah the guitarist. Was in the Upsetters.

Ranny Bop first started teaching me certain things, my first few chords on the guitar. And then I started showing Clem. Then Clem came and told me that he found EFM in Clerkenwell and wanted me and him to go into business. Then we got the Cimarons to work with Clem to do all the backing tracks and stuff. The Cimarons played a very important role in my life. I can't leave them out. They weren't really doing anything so they had nothing to lose by coming into the studio and doing something, giving them a few pounds.

Clem did a tune called Summertime sung by Domino Johnson, who was also another John Kelly boy. That was the first big song that Clem had. Delroy, being entrepreneurial as a kid, I set up this youth club thing in Bet Berl Hall [in Willesden], a regular Monday night thing where you had talent shows going on sound system. Big Mikey Campbell and I were running this sound system with a guy called George. Everybody used to come, and that was where we first started playing all these tunes and people thought they were good. It's a cult tune up until this day - the reggae version of Summertime.

Then Junior English also did a couple of tunes with Clem as well. Remember, we said that Junior was the first one amongst us who really started to sound professional. That was where I first met Leon and those people that set up that group The Blackstones. I was involved with the group at Pama Records. I was involved with Denzil Dennis setting up a group called the Classics, who did a big tune called History Of Africa. I was always around people like Ijahman in Brixton. The group that became Greyhound, which was the Rudies. So because I got around, because I really wanted to do it, I knew all those people.

Moving around Chalk Farm and Trojan, you must have known Dandy Livingstone?

Dandy Livingstone was like a big brother to me. He gave me a lot of help back in the day. He was somebody else that was really down to earth and always helping people. He's a really good human being. There are a lot of these people in reggae music and I think that's what makes reggae special. Yes, you've also got lots of people who want to come and push up their chest but those are the people that don't really have any talents, so they've got to really flaunt their ego! (laughs)

How did Rasta come to you?

Bob Andy was the first person where he and I really started to reason. People wanted to be conscious back in the days. I mean, I met Max Romeo and Max did a tune called Let The Power Fall For I, but I don't know if that was a real Rasta tune. Because everybody kind of had “soul head” Afros in those days. I used to reason with Bob Andy. Because Bob Andy was the first person that was a Rasta person who had Rasta views. I met Bob Andy before I met Bob Marley because Bob had the Young Gifted And Black hit. They used to live near where I used to stay down at St John's Avenue side. Bob Andy was the first person that I started talking to about Rasta.

But when I met Bob Marley now, he was fully kind of there. You could hear it in his music because they were that way. The Wailers were really a big influence even before I met Bob. And I didn't know that Peter Tosh was the same Winston that I knew back in the day. Because it was me that actually told Bob to go and get them [the other Wailers to come over to London]. Bob Andy was an influence, there were all the elements of Clancy Eccles and people like that who used to make some Rasta music. The group called the Ethiopians were one of the first groups that I ever heard singing about Rastafari. Songs like Know For I - you've got to come right over [Bongo, Les and Bunny] - good tune.

But the Rasta thing was always there in the music somewhere. Because Count Ossie was way back in the day. And my uncle Duncan, although he always had a Christian thing about him he always used to talk about Haile Selassie and Marcus Garvey in the house. He was somebody who was always talking about that pan-African thing. Because they used to smoke weed back in the days with the sound. Lenny The Lion, my brethren David who used to own Lenny’s sound. But those people were kind of what we used to call “Beard Man”. Because before Rasta you had Beard Man. I don't know if you heard of Beard Man?

From tunes like Beard Man Feast by Max Romeo.

And Beard Man Shuffle. Those people with the sound system, a lot of them were Beard Man. A lot of people that came from Jamaica during the 60s had a kind of Beard Man mentality. It was a very upfull Haile Selassie, looking tight people who were very dignified. Rasta people have a certain amount of respect and awe and the Beard Man had awe. The Beard Man was kind of a rude boy but he wasn't really a bad man. He always looked dignified but he would always have his ratchet or his weapon you understand? (laughs)

So we need to look at that whole development because I'm going to feature a lot of this stuff in my book. We have to know the whole evolution of Rastafari and why it was that you had people like Count Ossie at his place over at Wareika Hill. I went back to Jamaica in the 1970s and because [thanks to the Virgin deal] I had the money, I could go everywhere and I did! (laughs) I used to go all over the place and go and link up with some of these people.

Read Part II of this interview where Delroy Washington talks about getting to know Bob Marley, Aswad and Dennis Brown...

PHOTO CREDITS: Felix Foueillis - United Reggae (news graphic), Leslie Ford/1st View Entertainments (photo in gofundme screenshot)