Bob Marley & The Wailers ADD

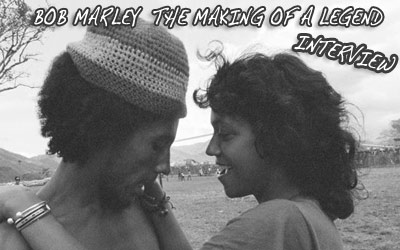

Interview: Esther Anderson - Bob Marley Making Of A Legend

08/11/2012 by Larson Sutton

Independent filmmaker Esther Anderson is known to many for her work in the spotlight; as a dancer, model, and award-winning actress alongside Sidney Poitier in 1972’s A Warm December. Yet, the Jamaican-born star’s role behind the scenes developing Island Records was pivotal in bringing many of the nation’s musical acts to international prominence, including the casting of Jimmy Cliff in The Harder They Come, and, as the subject of her new documentary, collaborating with a young Bob Marley just prior to the meteoric rise of the reggae superstar. Ms. Anderson, 66, spoke to us from her London home a few weeks before the worldwide online launch [August 6th] of the film Bob Marley: The Making of a Legend.

Your film is Bob Marley: The Making of a Legend. What is the significance of that title?

A long time ago I was collaborating with a Time Life reporter and she came up with the title. She said, ‘It’s the making of a legend, what happened to the legend, and what is a legend.’ The word legend is used for something that doesn’t really exist; it’s a myth or cult that you can create, like the Loch Ness Monster, or Bigfoot, or Buddha’s Tooth. Why we use the word is because, in fact, of all the work that went into putting together Rasta reggae, this image, to put this music out. Within the legend of say, the Loch Ness Monster, tourism comes to Scotland. People come to India to see Buddha’s Tooth, though they never get to see the bloody tooth. The community makes a living from that. In Jamaica, unfortunately, that is not what has happened. The legend has moved into the tax-free havens of record company owners. We hope to bring back a discussion, a discourse over this word legend. It’s all well and good to call someone a legend, but is it real? Next week, they’ll just call him God. And he (Marley) would’ve been sick to his stomach, would’ve kicked a football in your face if you called him a prophet.

Was partly your aim, then, to de-mystify Bob Marley?

I want to show you Bob Marley and Peter (Tosh) and the other Wailers as the young rebels they were, as we grew up together, living and working to do something for our country. We all came out of that revolutionary mold. We are in the same age group, and the same educational system. I happened to go a little further, having gone to finishing school in England to study drama, and I was very pretty. I was not exactly black, and I was allowed through the door, and got to make movies.

What motivated you to tell your side now?

Jonathan Demme said to me, ‘Esther, you were there at the very beginning. Make your own film.’ And he’s not the only one that said that to me. Even Chris Blackwell said, ‘If you gave it to anyone else, they would water it down.’ Yet, later on, when they (the Marley documentary filmmakers) didn’t have enough stuff in their archive they still had to come and infringe on me. They have about six of my photographs, my clips, in their trailers. Here’s Ziggy Marley on TV talking about unseen footage, and it’s my stuff. You’re referring to the parts of your movie used in Kevin Macdonald’s Marley documentary?

You’re referring to the parts of your movie used in Kevin Macdonald’s Marley documentary?

Everybody has wanted to use my tapes, tell their version of the story, often taking it out of context to tell it the way they want to. I said, ‘Enough is enough.’ When Kevin Macdonald came to me, asking to use my footage, I said, ‘No, they can’t have it.’ Yet, they still went and pirated my stuff in their film. That I will deal with later on.

How did the tapes fall out of your possession?

There was a boy that I had with me in Jamaica, essentially a groupie that begged and begged to come along, who operated the camera from time to time. And I have a feeling about him and the tapes and camera disappearing. I was told about ten years ago that the tapes were found in a garage in Canada. I got just a little bit back. There is still a lot missing.

At Island Records you joined with Chris Blackwell as a way of exposing the music of Jamaica to the world. What are your thoughts today about him?

I come from a very strong background in Jamaica, and I don’t buy into any of this myth-building. It’s all Chris Blackwell, my ex-partner. He has a team of people that has been creating the myth. The guy (Bob Marley) has cancer, and Chris Blackwell is going to appear in the film, the same film he is executive producing, and say he didn’t even remember that he had cancer? And Bob is supposed to be important to him? It’s unfortunate that people like Junior Braithwaite and Cherry (Smith) don’t get any credit. Simmer Down is Junior singing, not Bob Marley, though it sounds just like Bob. People like Lee Perry, who had such an impact, he’s huge in the history of reggae, but he’s been squashed by the one person who wants to take all the credit for Jamaican music and that is Chris Blackwell. Sorry, but that is the truth.

One of the revelations of your film is your encouragement of the Wailers to embrace the Rasta image. How did that come about?

I talked to the boys individually. Peter said to me, ‘I’ve tried so much, but my hair won’t grow.’ I told him to stop combing it, to wash it with a soft shampoo and conditioner, and the hair will grow out naturally. Well, you see how many years it to Peter to grow his locks. Family, Carly, Wire Lindo; none of them have it. Eventually they did, but it took some time. Bob is a half-white guy so his hair came easier.

How important was the Rasta image in the development of the band?

The first three albums definitely broke the mold. The live album crossed over. That’s when Al Anderson was taking guitar solos the way a rock audience was used to hearing in a rock band. We never had anything like that in Jamaica before. When I heard the Catch a Fire album, I fell in love with the guitar thinking it’s Peter Tosh, and Wire Lindo (on organ), when it was a white guy playing the organ, “Rabbit” (Bundrick) and a guy in America (Wayne Perkins, guitar) doing it. Catch a Fire was sitting on the shelf. People talk now after 40 years about the cigarette lighter (cover art), but what the hell does that have to do with a young voice, of a young band, coming out of Jamaica? It was an idiotic design. Eventually it was redesigned with my pictures, with Bob smoking a spliff. All of these things, the poster, the T-shirt, with his image on it, putting the Rasta, the smoking, the music all together were important. Also, getting Hope Road as a building where they could write together, practice together, just as the white groups did it here in London.

How did your personal feelings about Bob influence the film you shot?

Bob and I were in a relationship, but as an artist I was pursuing what I was doing in London. I started as a filmmaker, and I wanted to use the camera to get the blueprint for a good documentary. I never got to make it because Bob and I had broken up.

Ultimately, how do you feel about the way Bob’s life turned out?

I’m glad that he achieved his goal of getting his voice to the masses. He always said that the music will go on and on until it reaches the people. He believed in himself, and I believed in him. The ‘man and woman’ thing didn’t really come between us. In the movie I say I leave, but I couldn’t ever really leave. He was in my life until a year before he died. I wish that he was still alive. He had a lot of money, so there was no way he should have died from melanoma cancer in this day and age.

In the film, regardless of the personal connection, you imply a sense of civic pride or duty to use your celebrity at the time to help your fellow countrymen.

It’s the way I was brought up. I come from some incredible pedigree, and it’s a reinforcement of where my family came from. I’m not some Kingston ghetto girl. I was a friend of (Beatles manager) Brian Epstein and (Rolling Stones manager) Andrew Oldham. I grew up with these guys as a young dancer over here. Whenever there was a dance coming out of Jamaica to be demonstrated, it was me and my sister on English television; how to dance ska, rocksteady, all of that. The Wailers were the last part of my engagement with Chris Blackwell. Before that I was helping all of them. Millie Small was the first artist we brought to England. I did everything with her. Jimmy Cliff, I coached him right here in this flat where I later wrote I Shot the Sherriff with Bob.

Are you pleased with the reception of the film thus far?

It’s been one year of promotion I have done. A lot of major film festivals, won about three awards. All of the festivals have been by official selection. We have not paid to be in any of them. I’ve seen men cry, women cry. Young kids cry. To see how young he was. It’s touched a lot of people.

What impact do you hope from your film?

I’m happy to present it to the world and let them make up their own minds. A man from the Jamaican Ministry of Education came up to me after a screening in Miami and said, ‘This movie should be in every school. Then kids would see it is not easy to become Bob Marley. You’ve got to work hard for it.’ I want young people to know, with their video cameras and iPhones, it is content that matters. You can speak through this new art form; put it online, stream it to the world, and have your voice heard.