Helmut Philipps ADD

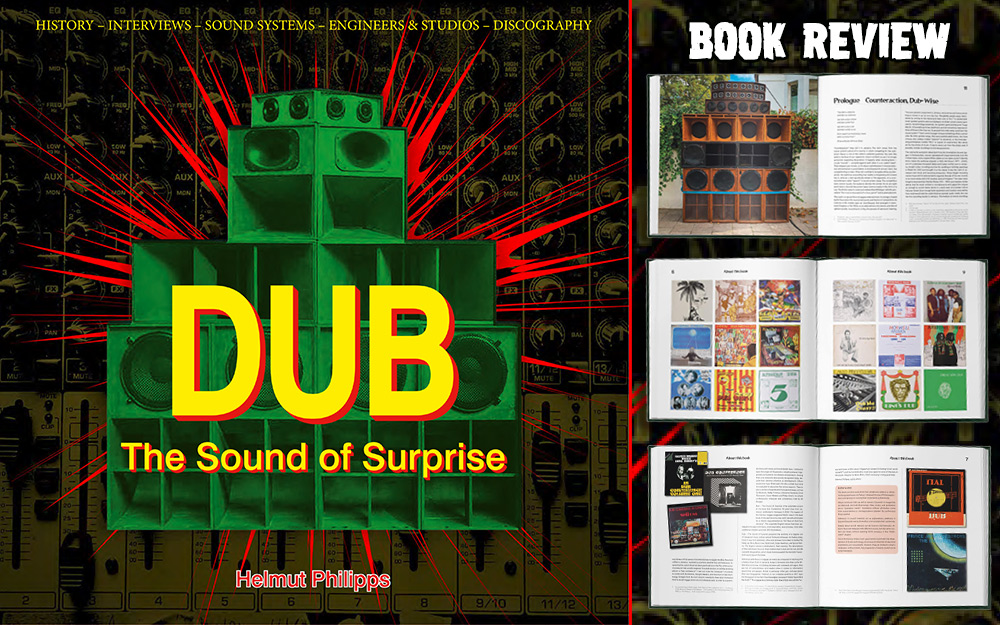

Book Review: Dub - The Sound of Surprise

11/16/2024 by Angus Taylor

For over ten years, German music writer and engineer Helmut Philipps quietly and diligently assembled his book on dub. He could often be found backstage at shows and festivals in Germany and the Netherlands, or visiting Jamaica, chasing down interview subjects, gathering the strands of his ambitious history of the most influential music form ever to sit on the B side of a single.

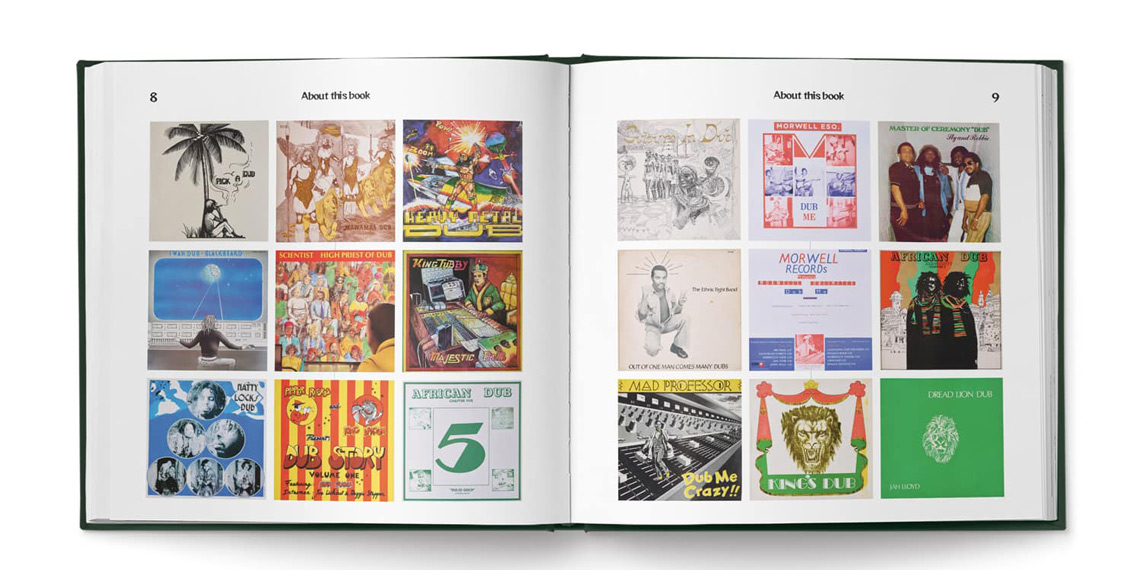

In October 2022, the book was self-published in German as Dub Konferenz, topping the Riddim magazine book poll twice, and getting an accompanying exhibition at Reggae Jam Festival 2023. This year, it has been translated into English by Reggaeville's Ursula ‘Munchy’ Münch, and published by Edition Olms under the new name Dub - The Sound Of Surprise (a phrase taken from a 1976 Melody Maker article by Richard Williams). It contains two new chapters, one on dub in the USA and another on Roots Radics’ drummer Style Scott. Thanks to the exhibition assets, it also has colour photos and a browsable coffee table format.

While the text is academic in its crediting of sources via footnotes, Philipps takes care that his language is as clear for the layperson as possible. As a trained engineer, he asks questions that solicit answers from his subjects beyond the scope of most reggae journalists. He is therefore able to chart the history of dub in terms of the technology available to its practitioners with a simplicity and clarity not seen before in a reggae book. Only the articles of Chris Lane have so deftly fused studio and writing craft.

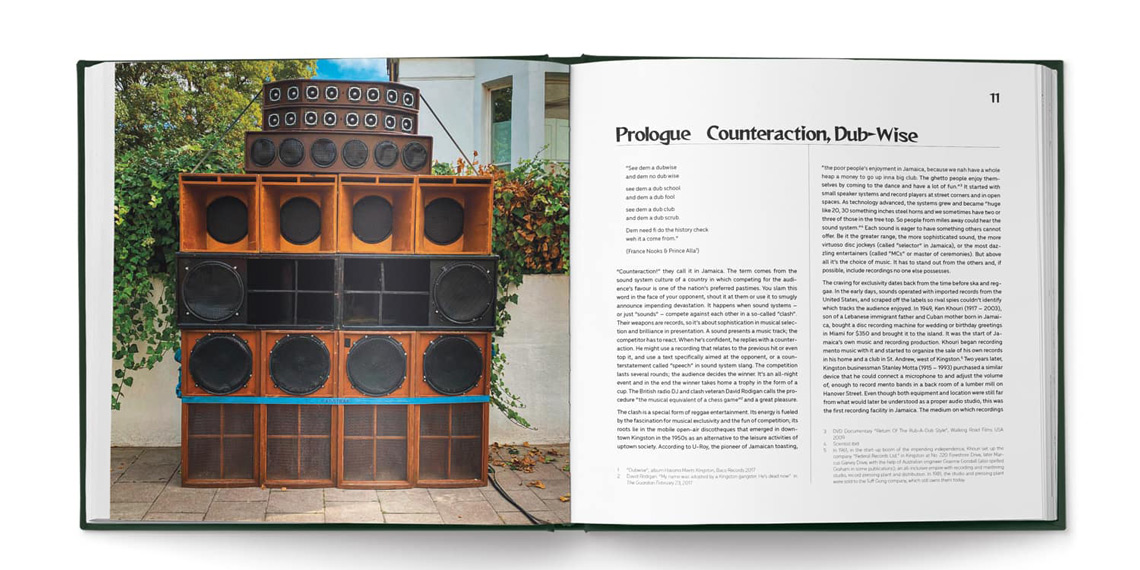

In studying dub, Philipps noticed that key Jamaican studio pioneers Coxsone Dodd and King Tubby were jazz aficionados. Dub, in its deconstruction and reconstruction of well-loved songs, focusing on individual instruments, is similar to jazz. The text is peppered with references linking the two forms. Even the structure of the book could be said to resemble a jazz tune: the opening few chapters being a conventional narrative history of the development of dub, the middle chapters zooming in on individual practitioners like soloists, then relaxing into some freeform riffs on the nature of dub itself.

Despite the book’s discographies being very album-focused, Philipps is consistent in highlighting dub’s connection to sound system in Jamaica. While a dub LP for its foreign devotees is a complete listening experience, even the busiest and most experimental dub was designed as a backdrop for a deejay or toaster to take the mic. He also clearly draws the line between UK dubmasters responding to the Jamaican tradition such as Mad Professor and Dennis Bovell, and what came after.

When assessing known dub legends like King Tubby, Philipps’ technical nous allows him to question some myths about the great man. His framing of Tubby as the populariser rather than the inventor of dub, could equally be applied to key players in his story (U Roy elevating the art of deejaying via Tubby’s sound system and drummer Santa Davis, whose work with Tubby ‘bust’ the already-existent ‘flying cymbals’ pattern). Philipps supplies a much-needed aerial view on the complex and volatile controversy involving Scientist, Linval Thompson, King Jammy and Greensleeves. He is similarly forensic on how Lee Perry got his Black Ark sound and why no engineers could operate it.

Crucially, he gives welcome focus to dub's lesser appreciated figures. He is enthralling on Errol Thompson, and moving on Sylvan Morris, whose reputations will be rightly elevated by his work. The same can be said of his interviews with Errol Brown, Pat Kelly and Barnabas. The chapter on Channel One, the result of Philipps’ most time-consuming and hard-won interview with Ernest Hookim, is dense but fascinating. As is the reason why ‘engineer’s engineer’ at that studio, Souljie Hamilton, isn't better known (he didn't want to be).

Philipps’ technical expertise means he is occasionally quite rigid in his arguments on more cultural matters. His assertion, influenced by Austrian musicologist Maximillian Hendler’s writings on jazz, that since pre-slavery African societies didn't have electricity, their influence on dub is negated, is a curious one. The very nature of ancient ancestral memories is that they are 'inborn' and unverifiable - certainly to someone from outside the culture - so little headway can be made here. This is one of several counteractions to US academic Michael Veal's 2007 book Dub - Soundscapes And Shattered Songs In Jamaican Reggae (recalling UK academic Brian Ward’s Just My Soul Responding critiques of Nelson George's The Death Of Rhythm & Blues). Likewise, Philipps’ dismissal of mento as a colonial pastime ignores Dr Carlos Malcolm's theories on its Cuban and Central African lineage in his book A Personal History of Postwar Jamaican Music.

More persuasive, if similarly ambitious, are Philipps' arguments in his freeform closing chapter, that much post-Shaka dub-influenced music is not really dub. His reasoning, that what passes for dub has departed from its Jamaican roots, will please Euro steppers’ vocal critics. But time is the master, and language evolves. The word “dubplate” no longer means what it did in the 70s. The word “ska” to foreign next-wave scenes encompasses a mish-mash of 60s Jamaican music. The word “singjay” has loosened considerably. Dub, like art, is what people say it is. Whether it's any good, is another question.

Yet these minor observations are ultimately peripheral to the main thrust of the book, which is the development of dub in Jamaica and its offshoots. The true test of its collective worth is whether it will be added to reggae’s historical canon and used as a resource by students and journalists to understand the music. The answer is a resounding, spring-reverberating ‘yes’.

Munchy's translation is everything you would expect from someone so fluent in English (although the deep-voiced Eddie Grant might take exception to the suggestion that he ‘whined’ when inspiring Bunny Lee to name his musicians the Aggrovators!). She also assisted with contextual content on one of the new chapters.

The book's layout, where its colour photographs and Q&A interviews break up the main text, recalls the format of the Rough Guide To Reggae by Peter Dalton and Steve Barrow (who is mentioned several times). Given its invaluable utility, Philipps' work could be described as The Smooth Guide To Dub.