IJahman Levi ADD

Ijahman Levi Interview | 1946 - 1976 (Part One)

04/14/2025 by Angus Taylor

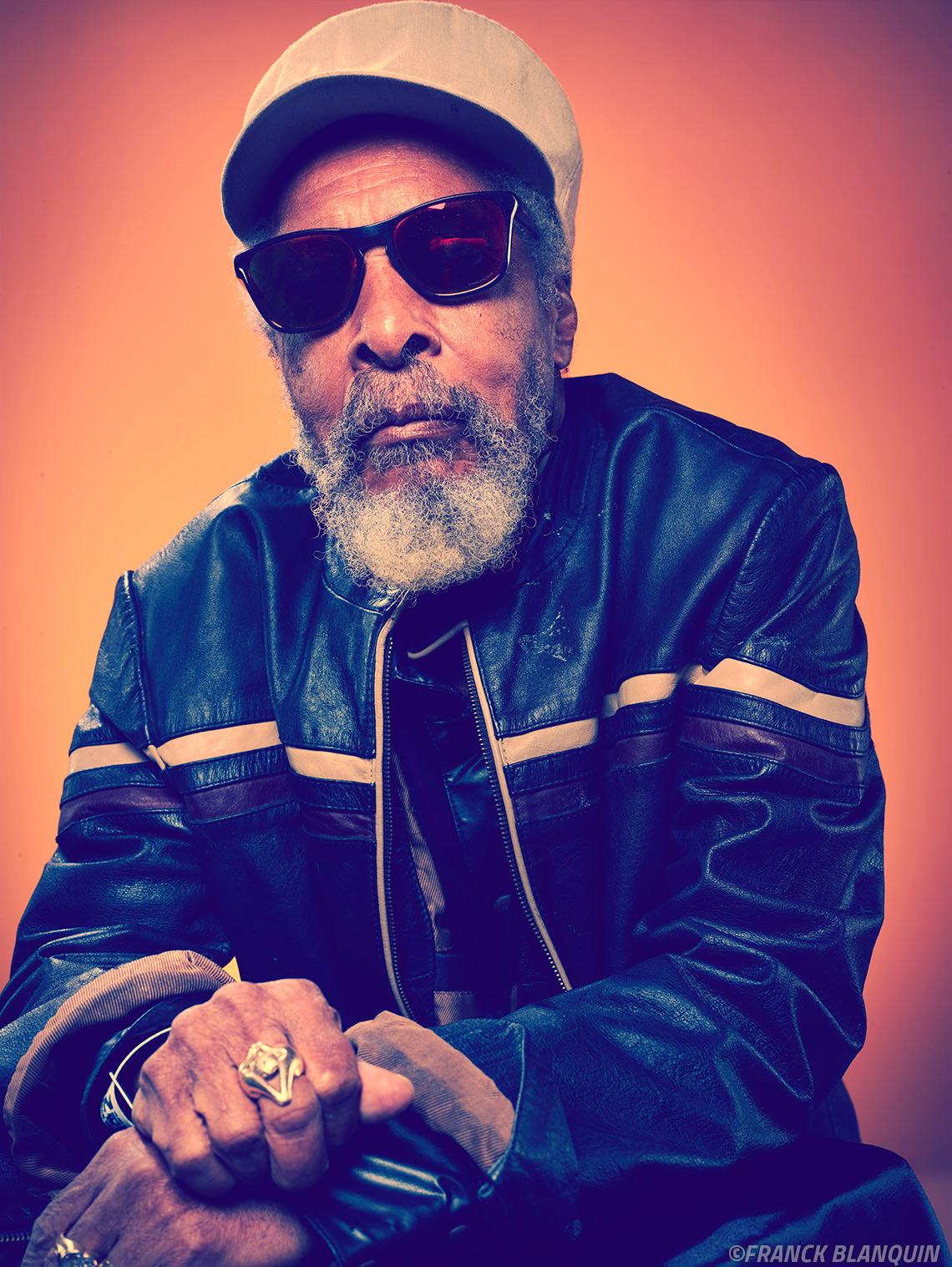

Of all the reggae singers signed to Island Records in the wake of Bob Marley, none were quite like Ijahman Levi. A deeply spiritual Rastaman who played a 12-string guitar and sang mystical songs that exceeded ten minutes in length, he couldn't have been further from the rough-voiced deejays riding classic riddims that appealed to London's punks in the late 70s. His music had more in common with Fela Kuti’s marathon workouts, Isaac Hayes’ opulent Walk On By, or Jah Shaka’s all night dub sessions.

His story is one of perseverance, resilience, great loss and a determination to do things his way. Born Trevor Sutherland in Christiana, Manchester, Jamaica in 1946, he grew to his teens in Trenchtown around Bob, Alton Ellis, Stranger Cole and Joe Higgs. After an unsuccessful audition for future Island founder Chris Blackwell, and an unreleased single for Duke Reid, he left for England where he performed soul and cut soulful reggae as The Youth.

Tragedy struck in the early 70s when he was sent to prison following an altercation. There, with little to do but write songs and read his Bible, he experienced a profound spiritual awakening. Estranged from his wife and children, having served his sentence, he began recording as Ijahman Levi for producer Dennis Harris. His initial singles, including the poignant reflection on his losses, Jah Heavy Load, and the 12 Tribes inspired I’m A Levi, came to the attention of Chris Blackwell who signed him to Island to remake them.

The two albums that followed were unlike any roots reggae releases at the time. Born of one set of sessions at Joe Gibbs Studio in Kingston and produced by Geoffrey Chung, the 11 tracks, several of epic duration, were divided into two parts. 1978’s Haile I Hymn Chapter 1 (containing extended renditions of Jah Heavy Load and I’m A Levi) and 1979’s follow up Are We A Warrior, eschewed traditional radio or sound system friendly formats, for lavish, majestic arrangements and messages that refused to be condensed.

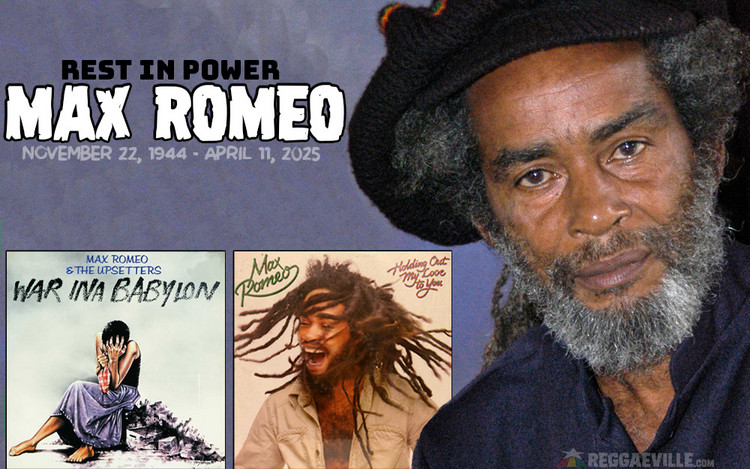

The LPs have become enduring favourites for reggae collectors. But as Lee Perry, Max Romeo, Bunny Wailer and Burning Spear also found, the relationship with Island did not last. Ijahman retains a bittersweet memory of Chris Blackwell, acknowledging his importance, while feeling he did not get sufficient financial reward for his best known works.

In the 1980s and 90s Ijahman threw himself into a flurry of self-produced albums. He scored a lovers rock hit in 1985 with I Do, a duet with his second wife Madge, recut Jah Heavy Load over a digital dancehall riddim for 1993’s Gemini Man, and paid tribute to his friend Bob with 1995’s covers set Ijahman Sings Bob Marley. Having been canny in retaining earnings from his publishing, and feeling the mystical urge to record subsiding, he moved back to Jamaica at the start of the new century. He has since recorded one album, Versatile Life in 2006, via his French booking agency Mediacom.

Angus Taylor spoke to Ijahman via video call as he was preparing for his 2025 European tour. The journey begins with six dates on the Reggaeville Easter Special in Germany and Amsterdam, alongside Culture ft Kenyatta Hill, Romain Virgo and Mortimer. Despite the tribulations his career, Ijahman was in good spirits and full of laughter as he recounted his history.

The resulting, typically monumental two-part discussion touches on information already documented in excellent interviews by Ray Hurford, Carter Van Pelt and David Katz, but also contains some interesting anecdotal details. One is that Ijahman recorded an early pre-Island version of Are We A Warrior in Jamaica for 1000 Volts Of Holt producer Tony Ashfield, never completed due to a disagreement with Peter Tosh over the correct guitar part. On a similar guitar theme, is the revelation that Eric Clapton played on the Haile I Hymn overdubs and was deemed not the right vibe for release. Ijahman also addresses suggestions that the length of the songs on his Island albums were Chris Blackwell’s concept.

How are you? How are things in Jamaica?

Well, as usual the sun is shining. Everything is beautiful. And I'm smoking a big spliff. So I'm alright! (laughs)

So you're from Manchester parish originally?

Yeah, same place, right here.

Where you are now?

Yeah, I'm in Christiana. Christiana is my birthplace.

Are your parents from that parish?

I think I was told as a child coming up that my mum was from Clarendon. Clarendon is almost next door to Manchester. Borderline. And my father is from Manchester, so you can say they are almost together.

Was there any music in your family before you?

No, I'm original. I'm the original one. Let me say this to you, I've never heard my father sing a song. Same thing goes for my mother. So all this original thing is really I starting it as IJahman Levi.

So how did music start for you in Jamaica? Was it radio or sound system?

In my young days you did have sound system but I think I was too young to be going to that. So we do a lot of listening on the radio. We listen to a lot of American music on the radio, like Jerry Butler, Sam Cooke. But I just find that Jah giving I the gift which is my voice, I've been trying to sing from as a young child growing up. 13-14, everybody wanted to do something. Not thinking about a career because I was too young for that. But as time goes on you start mixing with, as you know, Joe Higgs. I said he's my tutor but he's not really my tutor. He has never taught me how to sing. I was just among them and I love his personality because in those days Joe Higgs was a dreadlocks Rastaman. And I really love the way he did harmony. And I was singing at the same time with my little partner. Nobody knows about him but his name is Potsy. He did the lead and I did the harmony. And I learned a lot by just listening to Joe Higgs singing harmony. That's where everything developed little by little from Trenchtown because you had so many artists. Or should I say so many singers.

It was the real singers’ place.

Yeah, yeah, it was just natural. Out of that now you become an artist. But it was just a thing that is in me and I just love it. The further I go I always get greatness coming towards me, I never get no disappointment. Even when I sang for Chris Blackwell the first time I never felt disappointed. I was just glad that I did sing a song for a white man. Because I didn't know it was a white man I was going to sing a song for. And the song that I sang to him is titled Why? And I still end up after 30 or 40 years still create a song by asking him Why? Because if you watch my show on Rototom I sing about Dear Mr Chriss Blackwell.

You released the song Dear Mr Chriss Blackwell Why as a single in 2016.

So it's a long, long story. But nevertheless in Jamaica while I was there, my mother and father decide to go to foreign. First of all, my father went to London. Then he sent for my mother and then together they sent for me in 1963. So it's when I came to England now I start feeling musically. A musical vibe. And so I bought myself a guitar and just little by little I start my first band in England by the name of the Vibrations. Yes, well, we were all learners. Nobody knew the difference from A or B. Just a lot of noise but we were together. And practice, like they say, becomes perfect. And little by little here I am. So I give thanks.

Going back to Jamaica, how did your family move from Manchester to Trenchtown?

All right, that's a history. First of all, I was born in Christiana. And to my knowledge, even though I live in the country now because I live in the same parish that I was born in, Christiana, I don't know any country life. I was born in the country but then when I reached around one year, a year and a half, I went to Kingston. The first home in Kingston I don't really remember. But when it comes to my knowledge that I have common sense and I can say ‘that is that’ we're stopping at Albert Street in Denham Town. And then growing up I end up in Trenchtown. And it was Third Street. And at the time Trenchtown was Trenchtown because it was not like now.

It has changed since then.

So that's where everything developed. People you meet, artists, you meet everybody. And little by little as a youth you just find your spirit trodding on the same line. Like for instance in Trenchtown everybody wants to make a record. Everyone. So the outlet was you go to Coxsone Studio, Sir Coxsone, or you go to Duke Reid or you go to Buster.

Or Beverley's.

Ah right. Many producers in those times. So I end up living on Third Street and there was also, God bless him, Stranger Cole. And I was in the same home with him and somehow he just said to me “Want to sing?” And I said “Yes, I'm singing”. And he said “Okay, I'll take you on a session one day”. Then the day did come and he took me to Duke Reid's studio on Bond Street. And he said “Sing” so I just sing. I wasn't surprised, I just sing. And then Stranger said to me “Come to the studio tomorrow”. So this studio at the time was Federal studio or West Indies Records. So I went in there and all the musicians were there. Roland Alphonso, Tommy McCook, Don Drummond, name it. But at the time I didn't know who they were. But now I know they were all there because it was the Skatalites band at the time.

This was ska time. The ska was just starting.

That's right. So I sing and I make my first record. A song named Red Eyes People. And the only time I've heard that song in my life was when it was played back in the studio.

It never released?

I've never heard the song. That's the only time. The first time I ever heard my voice is when it was played back Red Eyes People and I listen to it and I left the studio. And Mr Duke Reid came to me and he gave me £5. In those times £5 was a lot of money for a young man like me. So I can say I'm gifted by the first song I ever recorded in my life around the mic I've been paid. I got £5 so God bless Mr Duke Reid wherever he is. And also respect to Stranger Cole because he's the one that took me there. God bless him. So that's where it all started.

What about this audition that you mentioned for Chris Blackwell before you left Jamaica?

Well, that goes on before I did that session for Duke Reid. I was coming from school one evening and there was a musical session at Lyndhurst Road, they call it Champion House. It's a corner. Champion House and Maxfield Avenue. I heard music playing as a little boy coming from school and you say “Let me have a look and see what's happening”. And when I went in, they were auditioning artists. Jackie Edwards, he was the one that was auditioning whoever is to be auditioned. He was playing the piano. So I went in and he said “What are you here for?” I said “I'd like to sing a song”. So he said “Okay, sing”. He started playing his piano and I sang to it and he said “Okay, you're alright. Tomorrow I'm sending you up to see a man. His name is Chris Blackwell”.

At the time he was having his office in Halfway Tree. Right before JBC TV. All that is now changed but it was on South Odeon Avenue. So the next day instead of going to school I went to see this person. I don't know who I'm going to see but I'm going to see this person. So I went up to South Odeon Avenue and knocked on the door. Someone said “Come in” and when I went in, it's the first white man I've ever seen. (laughs) And he said "What are you here for?” And I said “Yesterday I was singing at the blah blah blah and I'm coming to see you today”. So he said “Okay, sing”. And I start singing my song “Why Why Why Why Why Why" and I continue. And then he said to me “You're not really ready yet. But one day you will sing. Go home and practise and when you feel you are good enough, you're ready, come and see me again”. I said “Okay sir”. Because of course in those times you say “Sir" because you're a big man and respect.

So I went and I wasn't feeling disappointed because I just know that I sing. But what amazes me is that it's the first white man. It's strange because Jackie Edwards didn't tell me what colour or who I'm going to sing to. He just said “A gentleman up there, sing to him”. I went home feeling good within myself and I started practising. I started singing a lot more in my home. Until the time came that I met Stranger Cole. I was around Joe Higgs. At that time you had Higgs and Wilson, Paragons, all these groups and singers. Oh my God, Jamaica's Trenchtown, it's a blessing. And as time goes on my father, as I said to you, went to England and sent for me and everything really started in England.

Did Joe Higgs teach you anything about the business side of music? Did he show you how to register your songs or learn about publishing? Because I know you successfully held on to your publishing throughout your career.

How can he teach me what he doesn't know? He himself didn't know in those times! (laughs) In those times, nobody thinks about publishing. I'm not judging a man for what he does. But in those times nobody was thinking about that. We weren't even thinking about money. You just know you want to sing a song. And for you to get the chance to sing a song.

So was it in England that you learned about these things?

Yeah, all my knowledge and everything regarding music was in England. England is the college. (laughs)

Some people have said that Joe Higgs was the one that taught Bob Marley about publishing. Maybe that was later, after you left?

Maybe that came a bit later because you're talking about 1972 now when Chris Blackwell met Bob. In my time with Joe Higgs it was the 60s. So maybe from that time until Bob Marley time, maybe Joe Higgs had some knowledge about publishing and all that. In my time we didn't talk about those things. We just knew that we wanted to do a song and hopefully you'd get the chance to do a song. And I did get the chance to do a song for Duke Reid. I got paid £5, wonderful in those times. It was a bag of money that was for a young man. Age 12 or 13. So I give thanks.

So when you went to England, was it Harlesden in Northwest London that you settled in?

Yeah, I arrived in London in Harlesden. Harlesden is my homegrown. (laughs)

Was it much of a music place in those days? It definitely became a reggae music capital later.

In that time I wouldn't say it was a musical place because when I reached there I was 15-16 something like that. It was blasted cold and you had to go get a work now. It's a different environment and coming out of the sunshine country to this cold place here, so you don't have the time to be going around and thinking about music. But as time goes on things change. Because after a while, I think, here comes Trojan. And from there you get Pama.

Mr Palmer and his brothers.

Right Mr Palmer. So little by little as it goes on in the 70s things developed musically.

You mentioned your first group, the Vibrations. How did they form and what kind of music did you play?

What kind of music was Vibrations? You know I said we didn't know A from B? So we just buy instruments. Each individual person bought their instruments and start making a lot of noise. And as time goes on, little by little you get to know what you're doing. So for instance, I bought a guitar. I've never played a guitar before so of course you have to practise and it takes time to practise to hold the chord C, to move from C to G. All those things there, it's like you're in a different world but it's a musical world. And we're all together. But we didn't do much working-wise. My group the Vibrations, I can remember we did work at a club in London named the Q Club. Count Suckle.

A famous place.

Right. That man. I can remember one night with my band, I can't believe it. I sing a song, Wide Awake In A Dream. I think at this time we played maybe 15-20 songs because we're a young group coming up. You don't even know what you're playing for because we didn't even talk about money. But I definitely remember that they booked us back the following night and it was because I sang this one song named Wide Awake In A Dream. And Count Suckle shouted out to the crowd and said “One more time! Come back tomorrow and do the song again!” (laughs) So that was my first introduction with that band. But we didn't stay together, not because of any differences but we just didn't get together because we were young and branching out. And then little by little step by step I made one record for Polydor. And Deram label, I think I did. I did do two songs, one for Polydor and one for Deram label [Meadow of My Love]. Something like that. But that was way back in the 60s.

This was a solo singer?

As a solo singer, yes. I think I had the name The Youth.

As Long As There Is Love is the song on Polydor?

That's right. As Long As There Is Love. But I can't remember all these things. All I can remember about that time is that there was this lady. And I hope that she is alive. Her name is Claire Francis. I can remember she said to me once at that time when I was in Polydor “You are not a great singer but you're a great songwriter”. And it never left my mind. “You're not a great singer but you're a great songwriter”. And I bear that in mind. She worked at Polydor.

But weren't you also in a group Youth, Rudie and the Shell Shock?

Right. You're really getting into my history! Give thanks! (laughs) So when Vibrations broke up and I'm out there getting into my career… I didn't see it as a career because I was still working in the factory doing machinery and all these kinds of things. I love music and it's in my blood. My partner, his name is Rudie. I don't know if he's still alive now. If this article should reach him one day, I hope he knows that I don't forget him. His name was Carl Simmons and he was working in the Q Club.

In those times you had Sam & Dave, you had Wilson Pickett, Otis Redding, the Supremes. Those were the soul days. In my time I went to perform in a place in Europe where I could only play soul music. Because they didn't even know ska music. So if you went and played ska they'd be like “Foolishness”. So nevertheless it ended up that this gentleman wanted to sing with me. I would like to put it that way. He wanted to sing with me. Because I was a singer at the time. Performing. And we decided to sing together.

There was a gentleman who used to be a promoter. He was also a boxer. For many years I've been trying to remember his name. But he was a boxer and he liked music. He put a band together and it was 13 pieces. 13 white man. But when I say white man I mean young people like myself. And at the time I decided to join the band. And myself and my partner Rudie, we loved to sing Sam & Dave and Knock On Wood and whatever it is, in those times. So they put us together and made Youth and Rudie and the Shell Shock show. And that is where I really like to say I get my experience performing as an artist. Because we start going on the road and we went to Italy and France. Not a lot of shows but we travelled. That was my experience of being on the road, on tour, doing your thing.

So we got along, but what stopped it was when my partner's mother got sick and she was in America. He decided to go to America to stay with his mother. And that's where everything broke down. There was no Youth and Rudie and the Shell Shock show. And when that happened, as you know, I got myself involved in trouble. And I went to prison. And that was 1970. That was the time when I was making music for Jetstar, Mr Palmer.

Did you do any music for Trojan?

No, I never got the opportunity to work with Trojan. Because Trojan was just down the road from me. I was in Harlesden and Trojan was in Willesden. So you move among people, you get to know them, they know you, but I never get to work with Trojan. But Mr Palmer is where I did my first recording there.

And by this time you were recording reggae?

Yeah, because reggae was there in those times before, when I was with my partner. But after he went away and didn't come back to London, I'm still involved of course with reggae. So I did my two songs for Pama. One is Fire Fire and Jesus In My Soul. And it's a learning process and you're in a college. You're in college, A, B. C and continue until you reach your maturity. So as I was saying I went to prison. And while I was in prison, I think I've sing it already and I say it to the world, the Spirit of Jah Rastafari came within me, came within I. I feel the vibes and I get my vision from Jah saying I must change my name. And I did all this around me because of my visions. I give thanks and praise and I remember I said to myself one day while I was in prison, “I would like to create a name that when someone calls me, they mention Jah in their mouth”. Not that I am taking on the personality of God or anything like that but it's just what's in me at the time. I'd like to have a name that when someone addresses me I'm hearing that they address God spiritually.

And I think about it and I can remember reading my Bible and the first letter in the Bible is I which is “in the beginning”. And I liked the idea and I said “Jah, I Jah, I Jah Son, I Jah Singer”. And I said “No, don't call me a son because I'm getting older in my life, so I won't be a son, I'm going to be a man”. So I put the words together I Jah Man. And I came out with the intention of singing in that name as I Jah Man. And then I reach the opportunity because there was this gentleman who was the first white man that move around black people and local people in Harlesden. But he had a Rolls-Royce. And he also had his sound system. He recorded the album with John Holt, 1000 Volts Of Holt.

And I think about it and I can remember reading my Bible and the first letter in the Bible is I which is “in the beginning”. And I liked the idea and I said “Jah, I Jah, I Jah Son, I Jah Singer”. And I said “No, don't call me a son because I'm getting older in my life, so I won't be a son, I'm going to be a man”. So I put the words together I Jah Man. And I came out with the intention of singing in that name as I Jah Man. And then I reach the opportunity because there was this gentleman who was the first white man that move around black people and local people in Harlesden. But he had a Rolls-Royce. And he also had his sound system. He recorded the album with John Holt, 1000 Volts Of Holt.

Tony Ashfield was the producer.

Tony Ashfield. He just loved to be around we as black people. And he had his Rolls-Royce and he was in music. So everything was manifesting at the time. And he did record 1000 Volts Of Holt when I was around him. And he wanted to record me also. So he took me to Jamaica and that's the first time I'm going to meet Mr Peter Tosh (laughs). Because it's strange, very strange. Listen man, you're taking me right back into my history. I went to Jamaica with Tony Ashfield, that gentleman there took me to Jamaica and he also was recording Gladdy, Gladstone Anderson. The one who played piano.

And we went to the studio and I can't forget this (laughs) I was in the studio and there's this musician who comes to play on the session. And the wonderful musician was Peter Tosh. And I'm young, I'm very young and I'm there with them and it's time for me to do my recording. So I start to sing the song Are We A Warrior. But if you listen there's a certain change in Are We A Warrior where it must change to that chord. If you don't change to that chord at that time it can't work. So I was singing and Peter Tosh was building his ganja spliff in what they call it corntrash. Doing this thing.

So I start singing and he starts to play his guitar and I said to him “The chord there is an F. You must go to that F. If you don't go to that F it can't make”. And I have to laugh when I think about these things but he said “Which foreign man come tell Rastaman about go to the F!” And the song was Are We A Warrior. And you know what Peter Tosh is like. At the time he was young and it's Peter Tosh and just free and just talk “This Englishman come from foreign and tell me to go to an F”. Him no quarrel but him talk about it and I said “Okay, alright, alright, alright”.

And I surprised him. I said “Give me a minute”. And I went to the car and I picked out my 12 string guitar. And I went back to the studio and I start playing my 12 string guitar and singing Are We A Warrior. And I show him “You see that F? You must go to that F!” (laughs) And he sits down and he looks surprised at me because imagine I come with a 12 string guitar, you know? I don't even know if he ever saw a 12 string guitar before. So anyhow the recording was done. But of course that session, the recording never released.

I was going to ask if there was an early version of Are We A Warrior that never released?

Yeah, that was for Mr Tony Ashfield. But the main recording at the time was the John Holt 1,000 Volts Of Holt. So that's what we went to Jamaica to do and he got that done. My thing was like after but of course it never complete because Peter Tosh didn't get the F! So that was that. (laughs)

Amazing story.

You are the first person I ever speak to these things about. So you're taking me way back into my history. And it's quite amusing to me now to see my age that I reach now as an artist because I'm coming from a long, long way now.

When you went to prison, did you write your songs in prison?

I always write songs. Where the inside or outside. Listen. When I went in prison I've got a lot of songs that I've written before I went to prison. My first wife Miss Beverly, she destroy everything because I go to prison, so everything for me was thrown outside and disappeared. Many of my songs which I have were on tape. In those times you have cassette tapes. So it end up that everything destroyed. So when I came back from prison of course the system and including my wife didn't receive me back at home, so I have to take the street. So when I came from prison I didn't come back into her home. My wife Miss Beverly that I sing about later.

You wrote a song about her that appeared on the Are We A Warrior album.

(laughs) Right, right. So I continue and I trod like the prodigal son, trod trod Earth creation and step by step.

So you went to Jamaica for a while and recorded with Tony Ashfield. But let's talk about the first singles you recorded and released as I Jahman. The original single version of Jah Heavy Load, I'm a Levi and the song Chariot Of Love. They recorded in England?

In England because it was in England that I create the name IJahman in prison. I'm telling you man, I'm really on a mission you know. I'm telling you, it's strange. When I look back at it now I just know it's the works of the Father. The Father is working with me. And working in we. Because when I came out of prison, the same year that I came out. It's the same year that they say my father went away. 1974. And the following year ’75 January I got a vision about Psalms number three. And I receive some message from a gentleman by the name of Mr Harris. At the time I didn't have I Jah Man as a name yet, I think they know me as The Youth still. And he said “I would like you to do a song for me”. And I said, “okay you just come from prison 1974, so you're free now, so you're getting into life”.

Because my wife, I was married she had four, five children - four children for me. At the time I came out and there was no one, so like I said, I was like the prodigal son taking to the road. And I got the message from this gentleman, Mr Harris and his label was DIP label. And he said “Okay, I'd like you to sing a song for me”. So the day I went in to do the song was the same night I get my vision, the night before I get my vision of the number three, if I can remember right. So when I went to the studio. I can’t remember the area.

In South London or Central London?

South London, yeah. Believe you me, I pass through it two weeks ago. I was in the studio and I decided to make the song. But I just couldn't remember no melody for the time while I was there. For 2 or 3 hours I couldn't remember no melody. And I'm a writer. I had many songs that I'd written when I was with Beverly and I had many more songs while I was in prison because I write songs, same way. But my brother, I understand now but at the time I couldn't understand. I just couldn't sing no other melody for the time when I was there but Jah Heavy Load. (sings) I've Got To Carry Jah Heavy Load. I said “What's happening?” It was very mysterious.

Now after so many years I understand it. Because it's the works of the almighty God. That had to be the first song that I had to sing. When I finished Jah Heavy Load, here comes Chariot Of Love, here comes I'm A Levi. I said “What?” It's like they talk about the genie in the bottle. The genie is locked in this bottle and if you don't pull the bottle he won't be freed. At the time I thought “My God, how come I wrote so many songs and I can't remember no other melody?” Even Mr Dennis Harris, he wasn't upset but he started to get a bit annoyed because I'm taking too long. “What happened? You don't want to sing a song?”

But after I see the spirit move within me it's like I could feel the almighty God stand up in me and say “Okay, do you want to sing?” I said “Yes, I want to sing”. “Sing Jah Heavy Load”. So I open my mouth and start play my guitar Jah Heavy Load. And oh my God, I can't believe after I finished Jah Heavy Load my brother, the spirit, just all I can remember is Chariot Of Love, I'm A Levi. I did get I'm a Levi before I met him because when I went to Jamaica, in 12 Tribes in Jamaica… even though I wasn't in 12 Tribes too long… I get to realise or discover that I'm a Levi. That's when I come from prison, go to Jamaica, 12 Tribes and they say “You're a Levi”. That's where a chapter a day, I get to “I'm born in the month of June” so that's who I am.

So that's when I went to the studio to do the song for Mr Harris, I'm A Levi. I did three songs. Jah Heavy Load, Chariot Of Love, I'm A Levi. And then I leave and I make my way. We didn't talk about money because like I said in those times we don't talk about money. We're just glad to get the opportunity to do a song and that is that. I have never been paid. It's just that in those times you don't talk about money and of course after a while he died. He died a couple of months after. But what it has done for me is it created me a name as IJahman Levi and I make a damn good song, Jah Heavy Load which started my career internationally.

On the original single of I'm A Levi with Dennis Harris there is a very loud sound like a drill on the dub on the B side. Was that one of your ideas?

No! Not my idea. All that came as a surprise to me. That is Dennis Harris idea! (laughs)

Read Part 2 of this interview about the making of Ijahman’s two albums for Island, becoming a prolific independent artist, and his upcoming European tour.