Linton Kwesi Johnson ADD

Linton Kwesi Johnson | Interview Part I

09/02/2024 by Tomaz Jardim

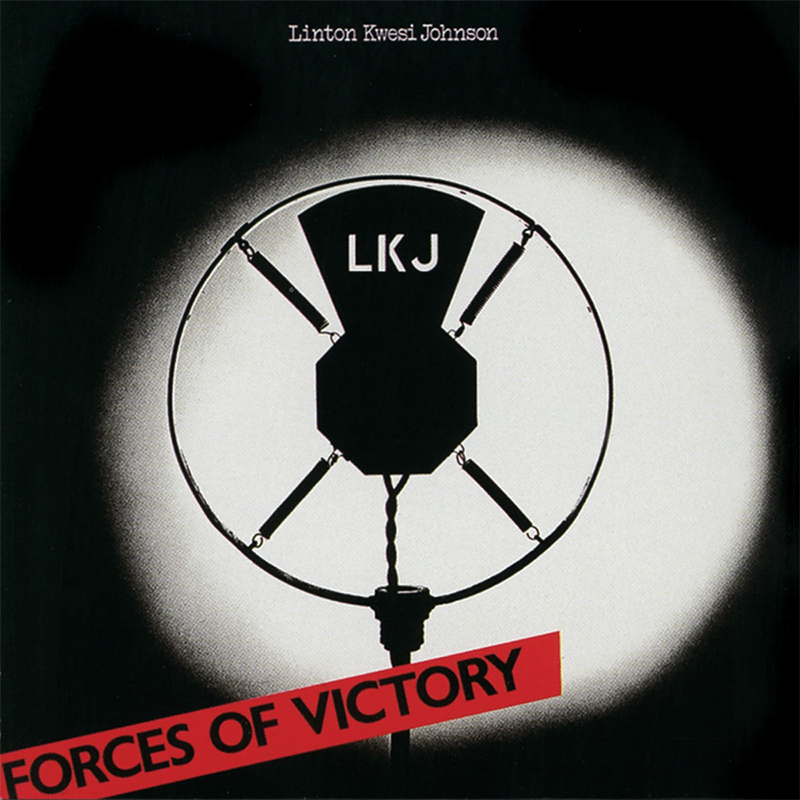

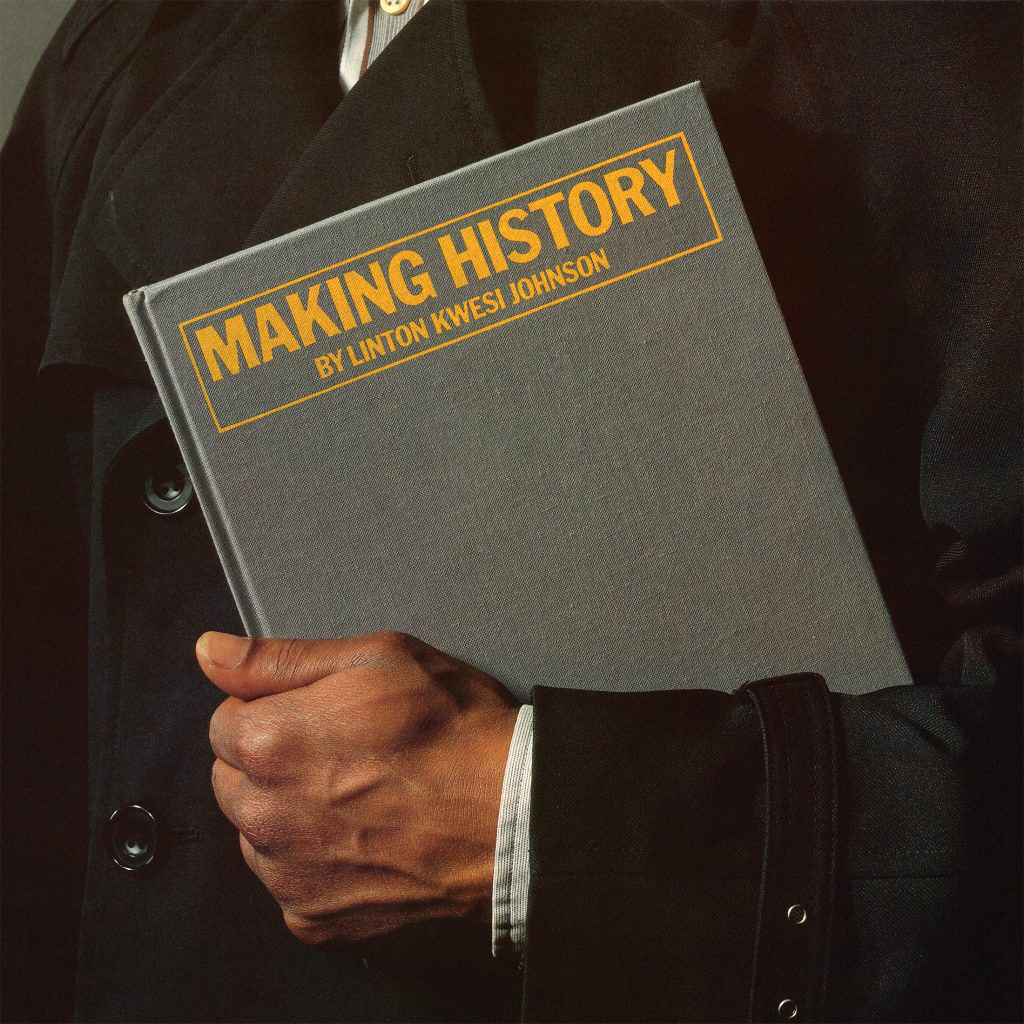

Few artists have the distinction of having their work define a genre. Yet Linton Kwesi Johnson’s name is synonymous with ‘Dub Poetry’, a term he himself coined to describe the new artform that emerged from the fusing of spoken word poetry with reggae music. Johnson, now 71, emigrated from Jamaica to the United Kingdom in 1963 and settled with his parents in the Brixton district of South London where he still resides. He has spent a career fearlessly chronicling the Black British experience and his generation’s fight against racism and social injustice. It has been fifty years since the 1974 publication of Johnson’s first collection of poetry, Voices of the Living and the Dead. Not long after, Johnson began experimenting with reciting his verse overtop of reggae rhythms in search of a wider audience for his poetry. With the assistance of Bajan-British master musician and producer Dennis Bovell, Johnson released his first album, Dread Beat an’ Blood, in 1978. This album heralded the arrival of something altogether new: a lyrically-centered, dub-infused and unabashedly political and poetic form of reggae music. Subsequent releases on Island Records, Forces of Victory, Bass Culture, and Making History, further developed this new style, with songs that were as lyrically rich as they were instrumentally compelling. The searing social commentary of songs such as Sonny’s Lettah, Street 66, Inglan is a Bitch and Di Great Insohreckshan came to define “Dub Poetry” and to inspire a whole generation of others who have sought to express themselves through this revolutionary new medium.

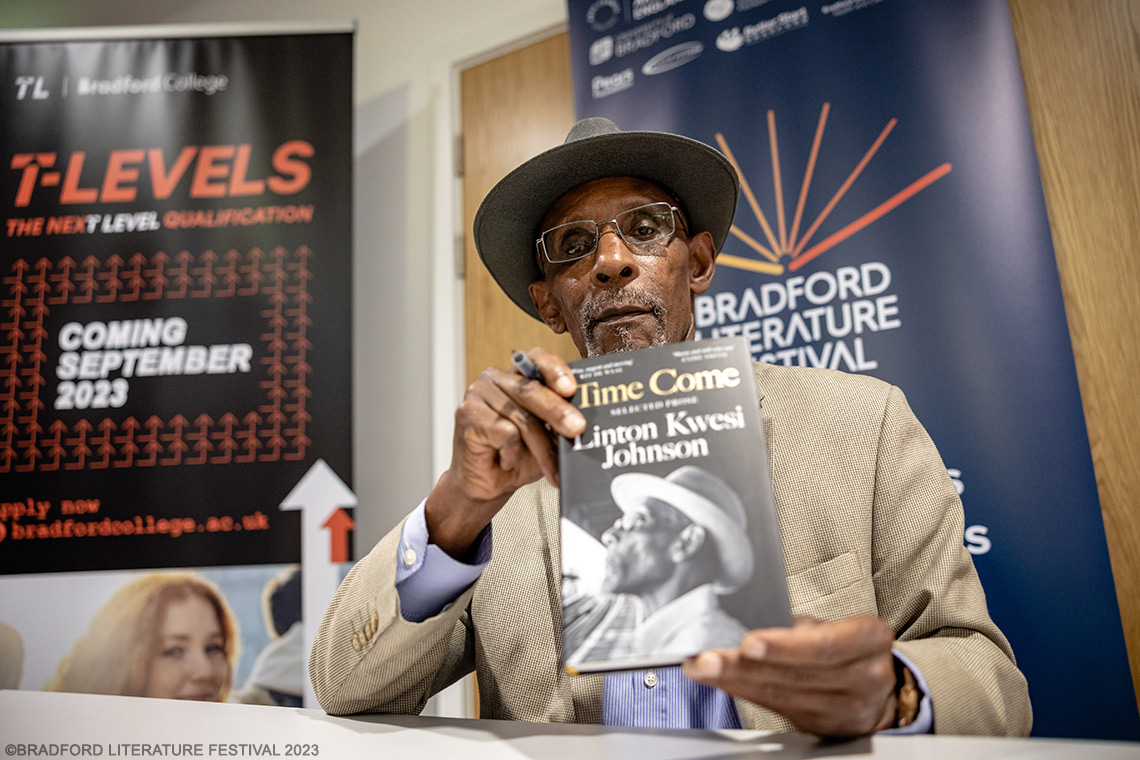

Though Johnson rose to fame through his music, his 2002 anthology of written poetry, Mi Revalueshanary Fren, earned him far-reaching acclaim and numerous formal honors. Indeed, the book made Johnson one of only two living poets – and the only black poet - to have his work published as part of Penguin’s Modern Classics series. In 2023, Johnson published his first book of prose, Time Come. The book, which draws together various writings on social, cultural and political issues over the last five decades, begins with a series of revelatory articles and reviews that Johnson wrote in the seventies about reggae music and its social significance. A paperback edition of the book appeared in April 2024.

In Part I of my interview, Johnson recalls his early experiments with reggae music, the process by which he both wrote and recorded some of his most famous work, and how that music was received both in the United Kingdom and in Jamaica.

You have spoken about the influence that the great DJs like U-Roy, I-Roy and Big Youth had on you, especially in helping you find your poetic voice. I'm curious to what degree the British sound systems may also have been important to your musical upbringing?

Sound systems were absolutely important, insofar as they provided the nexus for youth culture amongst second generation black youth from the Caribbean. Sound systems provided the nexus for the nurturing of a culture of resistance, because we were basically growing up in a racially hostile environment and the music afforded us an independent sense of identity. It was the only means through which we could socialize amongst each other and to assert our Caribbean-ness, our Jamaican-ness, to assert our roots, and to evolve an identity which gave us something to fall back onto, in the face of hostility. Town halls, youth clubs, house parties - - these were the venues until later on when sound systems got into clubs and so on.

Through your veneration of people like U-Roy, I-Roy, Prince Jazzbo, and other DJs, did you yourself ever attempt that type of performance, like toasting over records at a dance?

No, no, I don't think I was quick-witted enough!

I wanted to ask you about the circumstances that had you first put music behind your poetry, and about your working relationship with Dennis Bovell. What was it about Dennis that left you presumably feeling like he had the kind of insight to build the music to match your words? And how did this work? Did you present him with poetry and have him create music around it, or did you bring him something that was already fundamentally musical that he then finessed in the studio with you?

Well Dennis Bovell is a consummate musician. He lives, walks, talks, sleeps, eats music. I met him when I went to interview his band, Matumbi. They were playing at some club in London, and I was a freelance reggae journalist, or freelance journalist, full stop. And I'd known about him through the sound system world because he was the operator of Sufferer's Hi-Fi sound system. And they were based in Battersea. I'm from Brixton. But I think I heard him play at the Metro Youth Club up in West London. And then, when I was thinking of making a record, I talked to my friend from school, Vivian Weathers, who played bass on a couple of the albums. And it was he who said: "Well, of course you've got to use Dennis Bovell as the sound engineer, because these English sound engineers don't know how to record drum and bass properly to get that kind of Jamaican sound." Because in those days, British reggae was looked upon as being inferior to the real thing from Jamaica. So I got in touch with him when I got a deal with Virgin Records to do an album. And to be frank with you, I didn't know what I was doing! I had an idea of how I wanted the thing to sound. The basis of what I had was basically a beat and a bassline. And for the first couple of albums I did, I more or less sung or hummed the bassline to Vivian Weathers and then he played it.

Did you compose those basslines with an instrument in hand?

No, in the beginning, just in my head. Later on I would do it on the bass and simply play it for Dennis until he would say, okay, I got that. But before I even acquired a bass I would simply hum the bassline because it came into my head with the words. My first album, Dread Beat an’ Blood, I happened to listen back to the other day and I found that it was a disaster! There were places where my delivery was out of sync with the beat, but it was a learning process and Dennis gave us certain ideas about how to embellish the basic drum and bass track. And later on, he recommended musicians from his own band like the keyboard player Webster Johnson who played on Forces of Victory and Bass Culture. He was the Matumbi keyboard player. And he played stuff himself, like little intros, licks on his guitar, and a bit of keyboard as well. And we made Dread Beat an’ Blood, but that was a learning process. I mean, that was like being thrown into the deep end of the river and told to swim. By the time I came around to making Forces of Victory, I knew I had a better idea of what I was doing.

With regards to embellishment, I think of a record like Making History, for instance, as a pinnacle of a record with such an incredible level of musicianship. Can you say something about the vision for making that record, and how you went about it?

Well, the music is built around the poetry. Everything is built around the basslines. That's the basis of my musical compositions, the bassline. Everything is constructed around that. And I think by then, I was able to play a little bit of the basslines myself. And of course, Dennis played them competently. And we would sit down and discuss, once we'd laid down the basic drum and bass, piano, organ and guitar tracks. Dennis and I would discuss what kind of arrangement we would put with it. I'd make suggestions about horn lines and stuff like that, and Dennis would say, "Well, instead of that, why don't you do this?" And so it was a collaboration, the arrangements.

Another record to ask you about is LKJ in Dub, because there’s almost a subtle irony to the critical acclaim it received, in that your words are actually stripped away. To what extent was that your project? Are you somebody who actually gets behind a mixing board?

I sit with Dennis. He does most of it really. "You like this? You like that?" I'd say yes or no. By then I'd worked up enough courage to actually touch the desk, to put in a bit of delay here, take it out there and so on. But it's mostly Dennis's work with a little bit of input from me really. It's mostly Dennis's ideas.

Thinking about the composition of your songs and poetry, do you tend to have an audience in mind when you write or when you made those records?

Me! If it sounds good to me, then you know, I think I can go with that. It has to satisfy me. With regards to the composition of those poems that became songs, I saw myself as a poet trying to work within an oral tradition and at the same time trying to find a bridge to the reader. I basically saw myself as a Caribbean poet working in a Caribbean tradition that drew from orality. You know, Louise Bennett was the mother of Jamaican poetry. So from the very beginning, I think I had the authority or the confidence to use the Jamaican language as the vehicle for my poetic discourses. So a Caribbean audience or a Caribbean readership or a Caribbean listenership would have been my focus.

That being the case, were you therefore surprised by how far your poetry has reached?

Absolutely! Absolutely surprised!

What do you think accounts for that?

The music! The power of reggae music. We wouldn't be having this conversation if it were not for reggae music. It's all about reggae music. In the beginning, with the inspiration I got from the reggae deejays, I thought that in combining my verse with reggae, maybe I would be able to reach a wider audience with my verse, instead of just writing poems and trying to get people to read publications or to see them in literary journals or magazines or the odd poetry reading in a community centre or a youth club. I thought, yeah, if I could put my voice with some reggae music, I would reach a bigger audience especially if the music sounded good and it was danceable, you know? I was just trying a thing, so to speak. And it worked!

I know in those early days you also opened for various punk acts, presumably playing for an almost exclusively white audience. How did they perceive you and what provided that apparent link between the punks and the British reggae scene?

Well, we have to look at it in the context of youth culture and black and white youth socializing together, and solidarity amongst the unemployed black youth and working class white youth, and marginalized white youth and so on. At the time, during the punk rock era, there was more possibility, or a democratization, if you like, of creativity amongst youth. Everybody was trying to make a record. At that time, it seemed as though you didn't have to be like The Beatles to make a record or the Rolling Stones to make a record. And punk was a medium for self-expression for a whole a whole generation of alienated youth, black and white. And it was also a time of anti-racist struggles, and there was solidarity between black youths and white youths. I think the punk era provided me with a space to have my own voice within that whole thing. And it wasn't just me. I mean, bands like Steel Pulse were around playing the same kind of venues, and Misty in Roots, for example. They did a lot of work with Rock Against Racism. I think Rock Against Racism, with the benefit of hindsight, played a very big part in bringing punk and reggae together.

Would you say, therefore, when you talk about British bands like Steel Pulse, Misty in Roots, and of course you're among them, that there was a common sentiment that you shared, which perhaps sprang from your collective experiences at that particularly unique moment in time?

Well, reggae music for our generation was the basis of our cultural identity and a way of connecting to our roots. Reggae music for people like me was the umbilical cord that connected us to our roots, to our ancestry, and to our families and so on. And the music that inspired us was rebel music, the rebel music coming out of Jamaica, music of protest and so on. And we could relate the sentiments that we were hearing in the reggae tunes coming from Jamaica to our own situation here in this country. So there was a sense of continuity and we all shared that, whether it was Aswad or Steel Pulse or whatever. And even though when lover’s rock emerged, bringing forth a more ‘romantic reggae’ focused on boy/girl stuff and matters of the heart, the sound was still our sound, it was the Jamaican sound.

We have been speaking here primarily about Britain, but I'm curious what your reception has been like in Jamaica. Was your music distributed there? And did you perform there?

No, I wasn’t really distributed there, it was a kind of word of mouth. Few people had ever heard of Linton Kwesi Johnson. And then when Forces of Victory came out, I got some airplay on JBC, the Jamaican Broadcasting Corporation, but not much. So amongst a few people in the music world, and in broadcasting, and some literary people – only they would have heard of me. But I mean, I never had a big following in Jamaica.

I know you read your poetry there, but did you perform there musically at any point?

Yeah, in 1979 or 1980 I did a couple of shows for Peter Tosh. Peter Tosh used to have a thing called Youth Consciousness every year. And I did one with him at the Ranny Williams Centre in Kingston and one at Hellshire Beach in St. Catherine.

How was that experience?

It was absolutely terrifying! I mean, the people were just standing there sort of looking at me, and I'm thinking that they must be wondering, "Who is this guy, what's he on about?’"[Laughs]. Herbie Miller, who was responsible for spreading my name around in Jamaica and who was managing Peter Tosh had invited me, and he said to me, "Do six tunes." And so at the Ranny Williams Centre, I think I might have done three from Dread Beat an’ Blood and three from Forces of Victory. And by the time I got to the fourth number, a well-known JBC DJ called Baga Brown – I think he was murdered some years ago - he said, "Come off the stage now, man! Come off now!" But he was the only heckler in the audience, so I just stood my ground and I just got through my set. Back in those days, I didn't have a band, it was backing tapes. And I just put my words to the backing. And they weren’t used to stuff like that in Jamaica, it was like a new thing, but which later on became called “playback”, with people performing without bands. But it must have seemed weird to them at the time. Anyway, I got through the set, and I got kind of muted applause at the end of it. I survived! The second gig at Hellshire Beach, I was very well received. I did the same set and people liked it and I felt good about it. But that first show was… I mean, I was absolutely terrified! I mean, if they don't start pelting you with beer bottles and stuff, you know you've done an alright gig in Jamaica.

Forgive me if this question seems a bit tangential, but to me it relates to what we've been discussing and gets at the relationship between poetry and music that your work has straddled more explicitly than perhaps any other artist: What did you make of Bob Dylan winning the Nobel Prize for literature?

I thought it was wonderful because there are many people in the world of popular music who are great lyricists, whose lyrics can stand as poetry and stand very well. Because the division between the written and the spoken is artificial; poetry only comes alive when you hear it, whether you're hearing it in your head or you're hearing it spoken. It's the hearing of the poem that makes it live and breathe. So I was pleased that someone like Bob Dylan, who wrote great lyrics, and whose songs captured the zeitgeist and that addressed the human condition in ways which were accessible, was recognized in this way.

READ HERE: LINTON KWESI JOHNSON - INTERVIEW PART II

The interview appeared first in the FESTIVILLE 2024 magazine. Click here to download it as free PDF!