Sly & Robbie ADD

Interview with Sly Dunbar

05/15/2014 by Angus Taylor

Drummer Sly Dunbar is one half of production duo Sly and Robbie. He's also the driving force behind some of reggae music's greatest innovations.

He's changed the beat of reggae more than once. Most famously with the mid 70s “rockers” double drumming pattern at Channel One studios. But there's a convincing argument to be made for him having a hand in the early 70s flyers and the late 70s steppers rhythms - although in both cases the gracious Sly credits senior sticksmen from the Studio 1 era - Lloyd Knibb and Fil Calender - respectively for their invention.

Because, as well as being one of the most important drummers in popular music, Sly is one of the nicest characters to interview. Angus Taylor spoke to him shortly after the release of Underwater Dub, his latest album with bassist partner Robbie Shakespeare, about reminiscences from his past and projects for the future. Throughout Sly made clear his musical philosophy of commitment to moving forward by tweaking the standard sound of the day just the right amount - anticipating what the people want to hear before they even know it yet.

UNDERWATER DUB

Your new album with Robbie Shakespeare, Underwater Dub, produced by your friend and touring engineer Alberto “Burur” Blackwood, sounds like a dub concept album – the way all the filters and bleeps create a deep sea atmosphere. Did the underwater concept come in at the start or the end?

I think it came in at the end when everything was sent in to the guys in Germany. Burur and myself mixed it and we were thinking of a name for the record. We came with a few different names, they mentioned “Underwater Dub” and I said “That’s fine with me”.

We were going by feeling, instinct and doing things. Like in the old days where you just go in and do it and then we’d think about it after! All these things that people go crazy about – nobody knew how it was to be done, we just did it and it came out great.

> From early in my career I always tried to do things a little bit different. <

This is your second dub album with Burur – so even if you didn’t think about it being underwater obviously you wanted it to sound different from the previous one, Blackwood Dub?  We wanted to make it, not totally different, but just where you could see the difference – not repeating ourselves.

We wanted to make it, not totally different, but just where you could see the difference – not repeating ourselves.

From early in my career I always tried to do things a little bit different. I like to go out of the box but not taking it too far so that one wouldn’t understand what is happening. We just put little things in that you probably wouldn’t hear today in a reggae song. We use all the things that are happening in the industry today and then we go outside and do other things that perhaps a lot of people are not using.

We didn’t just use old rhythms like how some people do and just remix it. We’re thinking of the listeners and they want to hear fresh things inside of reggae instead of hearing the same thing being repeated so we added the old Syndrum and others effects like that. We just do crazy things sometimes on the spot. Someone says “Hey, put that in” and we say “OK”.

Last year you put out albums by Stepper Briard, a second album with Bitty McLean and the long awaited Shaggy album. Where the Blackwood dub albums are tailor-made rhythms from scratch, for those you looped old rhythms.

That’s because sometimes we sit and say “OK if we don’t reuse the rhythm and loop it back then somebody is going to do it!” So I will go in and I’ll loop something and send it to Bitty McLean and then he’ll do something and send it to me and say “Listen to this”. It’s just how you feel at the moment.

So will there be more Blackwood albums? People seem to like them.

Yes. We’re planning a series and we’re going to do a third one. I think people are getting to like it because there’s a concept and the sound we use is not used on any other dub album.

We’ve started working on some things that we’re going to use – we don’t know exactly what we’re going to do but we’re just going to get crazy. (laughs)

SLY AND ROBBIE ON TOUR

In 2012 you toured with Ernest Ranglin and Monty Alexander – although Monty dropped out after the initial Blue Note shows and was replaced by Tyrone Downie. What was it like touring with Ernest?

That was a great tour for us because Mr Ranglin is a great icon of Jamaican music. I’ve played with him in the studio but this was one of the first times for me and Robbie being on stage touring with him and seeing how he really used the guitar. Whatever he thinks of, he takes the guitar and does it.

Ernest would often use his guitar like percussion, tapping the fretboard.

Yeah sometimes myself and him would do that. I’d play the drums and he would play the guitar and we’d answer back to one another. He’d just use the guitar to do anything.

It was really good playing with those people. It’s a relaxing kind of reggae but at the same time it’s reggae and they are playing jazz overtones and whatever they want– that’s what makes it so creative. They don’t just burrow down into one area but everyone knows it is reggae.

> When we were young we were timid to play Jamaican music because we didn’t know if the people would accept it <

This year you’re in North America playing at Reggae On The River, Sierra Nevada World Music Festival and the Montreal Jazz festival.

A friend of mine just asked me if I was playing Montreal because he lives there and he remembered when I came there in 1975 playing with Jimmy Cliff when he did his first American tour! So a lot of people are looking forward to it because we don’t go to Canada a lot. I think we played a concert there the first time we went on the road with Cherine [Anderson] because Horace Andy couldn’t make it, so we took her and it was good.

I want to go there and just play how we play. Because long ago when we were young we were timid to play Jamaican music because we didn’t know if the people would accept it. But the reggae has grown and got popular and when you go on stage now you feel “I can play because people will listen and know the songs and the beats and everything”.

Burning Spear is also playing there – any chance of a collaboration?

I don’t know if we are playing on the same day. The last time I did anything with Burning Spear was when we did a show in New York with Sinéad O’Connor. Burning Spear came on and played percussion right through the whole set. It was fantastic man. And when we did the tour with Mr Ranglin and went to Dublin, Sinéad came up on stage because she wanted to sing some songs and we jammed three songs for her. It was wicked.

THE STATE OF REGGAE MUSIC

The Reggae industry is very concerned that album sales are down – albums top the Billboard Reggae charts having only sold a few thousand copies. You are a forward thinking person, so what is the future? Streaming? Live shows? Is the album dead?

I don’t think the buying public can keep up with the amount of records that are being released. Music is too easy to put together now. One time you would go inside a studio and you had to be six people inside the studio to make a record. Now a guy sits there and he gets a loop and boom he burns a CD and takes it to a guy at a radio station to play. I think for the future of the music people are going to listen and buy what they like and if they don’t like it they’re going to leave it alone.

But I think what is happening to Jamaican music is on the writing side we need some good songs. I think that has dropped off a bit with our music. If we could get some good songs and good production on them – not to over produce but to make it so it could go into any mainstream market - just like in the days of Desmond Dekker, Jimmy Cliff and Bob Marley, then it could be like that again. Then again the technology is moving so fast and kids have these things that can make music, so I don’t know if it’s going to work out but I think it’s just a cycle and it will come back around.

It’s interesting you mention cycles as there has been a lot of media interest in what some have controversially called the Reggae Revival.

I don’t use that word because that has always been there. What happened is the radio stations are funny sometimes. Sometimes they will play a lot of dancehall stuff. Then they go back and start playing some roots rock and one drop. But I don’t look at the reggae revival because it’s always been there. Luciano’s been singing it but they just weren’t playing it. People can give any name they want to something but the people who are in it will know that it’s not a reggae revival. It hasn’t gone anywhere.

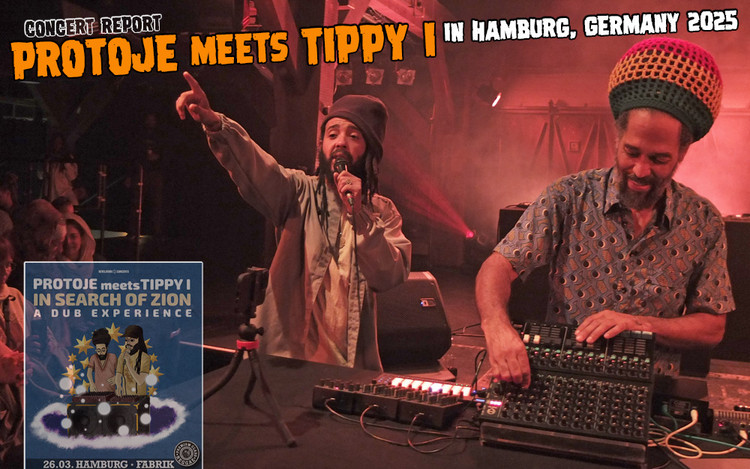

Leaving aside the name, it’s clear that artists like Protoje and Chronixx are drawing on your work with Black Uhuru and Ini Kamoze. You’ve recently played with Jesse Royal. Are you an architect of this so called revival?

(laughs) I don’t know… I remember Protoje came to check me because I knew his mother Lorna Bennett very well. He told me he used to listen to Black Uhuru a lot. For me it’s good that they listened to what we were doing and they like it very much.

But when you do something you have to decide how to move it forward and make it grow so it doesn’t get boring or like you are repeating yourself. This is where the trick is going to come in. So you have to always know the next step you’re going to make and what you’re going to do to keep people listening to your thing and make them want to check your next record because the next record is hot.

Whenever we were doing a Black Uhuru album I used to say to Chris Blackwell “What should we do next?” and he would say “Just keep it same way but alter something”. The album that won the first Grammy for Black Uhuru was the first album where we put horns in on a Black Uhuru album track. So you have to think “How are we going to upgrade it to the next move”. If they can do something like that and keep it then it will be good but we will have to see the next step. The other side of what you were saying about the internet is that it gives young musicians and producers access to so much great old music and archive footage on YouTube. Perhaps it’s harder to make something new when you could revive good music from generations before?

The other side of what you were saying about the internet is that it gives young musicians and producers access to so much great old music and archive footage on YouTube. Perhaps it’s harder to make something new when you could revive good music from generations before?

I think it makes it easier because when we were growing up we used to see things on television like James Brown or a foreign group and say “Wow, that’s great” but they can just log on to YouTube and pick up anything anytime. Sometimes go on YouTube and listen to some old R&B artists. It’s really like a school or university where you go and log on where once you never had that freedom to see. I think it helps them to learn and see.

But before the internet, a young artist might hear something, try to copy it from memory and because they didn’t remember it exactly they’d inadvertently create something new. Whereas now young musicians and producers can learn how to play the music you created with Black Uhuru exactly. And if they can play it well and it sounds good – why should they move it forward?

Yes! We used to listen and we probably didn’t hear it exactly and we’d recreate something around what we heard. As you say, they might take it for granted that this is good and they know exactly what they are doing because they’ve seen it. You’re right!

You popularised the Pollard Syndrum in reggae with Black Uhuru. They are all over the music of Alborosie and his live show is full of Syndrum – tell me the story of how you started using it.

I was looking at the transition when all these electronic things and keyboards were coming and when they went to this electronic drum I thought “Wow this is interesting. I want to get involved. I want to play a part in the whole transition.” So I brought in the Syndrum and said “I’m going to find a way to use it inside of reggae”. We used it a lot in Black Uhuru and then sometimes it can get a little bit too much so you have to use it a way that audience won’t say “I’m tired of hearing that”.

I thought “Everybody is doing the [imitates laser gun effect] so I wonder if that’s the only sound I’m going to get from it from it”. I started putting a lot of effects through it and playing with it until I thought “Wow I can do much more than that with it”. If you listen to a lot of Black Uhuru songs there is a [imitates helicopter sound from Black Uhuru] and that is a Syndrum playing. I recreated that sound in the Syndrum and put it in Black Uhuru and gave them that percussion kind of riff in the music and really make it in the groove. And on Grace Jones Pull Up To The Bumper that [imitates distinctive puk puk puk] that is the Syndrum playing. A lot of people don’t even know this is the Syndrum.

PROJECTS FOR THE FUTURE

Guitarist Earl Chinna Smith is a similar figure to you in Jamaican music – and you’ve been playing on his new project Binghistra.

Chinna is doing fantastic things down there. I go at 2 o’clock in the morning and say “Chinna I really feel good about what you’re doing with the Binghi Orchestra”. It’s a great vibration when they are jamming - as you walk down the street and you hear them playing you fall in a trance immediately. It just takes you in. It’s a wicked idea and the congregation of musicians down there is just fantastic. Every time I see Chinna I say “Man, that Inna De Yard thing you know, I’m glad you never migrated and you’re still here”.

The rest of Soul Syndicate went to California but Chinna stayed behind.

Yeah, I said “Chinna, trust me, God sent you especially to do this because you could have gone but you stay and just try to hold a little younger musicians together in the Binghi yard Inna De Yard thing”.

Your album with Aswad’s Brinsley Forde has been in the pipeline for many years - when is it coming out?

I don’t know. When I saw him the other day when we did this thing in London for Save the Children we were talking about it so I think he’s working on it. But I don’t like it when we stay on things too long. I like to boom boom boom and keep moving.

What else are you working on that you are really excited about?

I’m working with a female deejay called Danielle and with a group called No-Maddz. We have a record which is going to come out for them called Romance. I think they have a great image and everything but a lot of people don’t know that they can sing. So we’re trying to put together a little EP with 7 songs just to showcase their talent. We’ll still do stuff with Cherine and I’m helping out Fatis’ son Kareem on some of the productions. Sometimes Chinna will call a session and we’ll go down there and record in the yard. It’s just a bunch of us who are trying to think in the same way and create that kind of music and keep it alive.

There’s this album we’re working on called Taxi Gang and it’s slightly different – it’s dancehall and reggae but the sound we’re using is different from this dub that you heard. We just listen to a lot of records and see the direction the global world is going in and we try to mix a lot of things together – like take Latin and take Arabian sounds and mix them with Jamaican dancehall. We’re really making the music not for ourselves to enjoy – we’re trying to make the people enjoy and say “Let’s backtrack on the history of the music and the journey that it’s been on to come into this style”.

Tell me a bit more about this new Taxi Gang Project.

There is an instrumental we put out last year called Coronation Market where we used an accordion to play the lead. It reminded me of a mento situation where you’re in the country in Jamaica and you can see the woman coming through the field with the basket of fruit on her head. We named it Coronation Market which is a popular market in Jamaica where everybody from where I was born goes to sell their products. Even today people still go there to get good cheap food.

We started listening to what is happening globally around the Top 40 radio and I said “We can make some kind of dancehall dub and take it to a different stage”. So Lenky Marsden came in and helped do some keyboards and Robbie Lyn is coming in to do a Nyabinghi thing with Nambo Robinson. We did a version of Rockfort Rock which is El Cumanchero, a slow version like a Latin type of version. It’s really empty and kind of dubbish.

It’s almost ready. I’m just going to do one more track with Nambo. It’s a Nyabinghi track and he’s going to play a vibraphone kind of sound. I don’t know if you know the work of Lennie Hibbert?

Yes from Alpha Boys School.

Well we are looking back at something like that. Putting a lot of things back into the music that we grew up listening to which are not there now. A lot of people have been crying out and saying the music is not as soulful and real as it used to be so we’re trying to put back some of that element.

I think it’s going to work. People who have been following our career how we move along with the music and our development will probably enjoy it. Because we haven’t gone far away – we’re just putting new sounds and elements inside reggae. If it’s dancehall, it’s a dancehall beat with new sounds or it’s reggae with different things on top.

MEMORIES OF THE PAST

You’ve brought back elements of mento and folk music into the dancehall before. How big a part of your upbringing was that tradition?

I grew up listening to mento and calypso and all these kinds of beat like Kumina. When I made Murder She Wrote I was looking at the Kumina people and I started to make the rhythm around their body movements. I like to sit down sometimes and watch because this is where the original thing is coming from – from the movements of their bodywork. I still do listen to it at times and try to take elements to put into modern reggae.

In his book Reggae Going International, Bunny Lee said you were the first Jamaican to drum the flying cymbals with Skin Flesh & Bones. When I asked Chinna about the flying cymbals he said the first instance was Lloyd Knibb Moonlight Lover?

Yeah, he’s right. A lot of people didn’t know where it comes from. I heard Moonlight Lover when I was a youth before I even started playing drums. It had this sshhh sshhh and I was asking everybody “Who played that?” I was doing a session a couple of years ago with Jackie Jackson who played bass for Treasure Isle so I said “Jackie, Moonlight Lover has a flying cymbal. Who’s playing?” and he said “Lloyd Knibbs” and I said “Lloyd Knibbs played it? Wow”. Jackie said to me when he was playing it everybody said “What is that he’s playing?”

And when Ansell Collins called me to do Double Barrel I told him about it because Ansell played a little drums too. So when it came to working on Double Barrel I started playing sshh sshh and if you listen to Double Barrel you can hear that flying cymbal from when I was 15 years old. I didn’t use it again until it came to prominence with Here I Am Baby for Skin Flesh and Bones and then I used it again at Channel One for It’s A Shame for Delroy Wilson. But Bunny Lee was the person who really made it popular and called it the Flying Cymbal on all the Johnny Clarke stuff.

You played with Ansell on Double Barrel – some people say the song has its genesis in Ramsey Lewis’ Party Time – what do you think?

No no no. He just came up with it and said “Listen to this” and I said “Wow this is great”. Then we had a rehearsal, just me and him for one week straight setting all the parts.

You once told me you’d drummed on hundreds of Dennis Brown – especially Joe Gibbs stuff. You played on both versions of Money in My Pocket.  I did the first one for Joe Gibbs and then the second one when they wanted to recut it. I said if I was going to recut it I was going to play it differently because I couldn’t just go back and record the same thing. So I played straight four cong-cong cong-cong. It’s funny because last night we were at the studio playing around two o’clock in the morning and when we listened back to the drum pattern I played somebody asked me if I can put back the roll I did in the Dennis new one! I went cong-cong cong-cong and everybody went “Yeah this is tough”. Then I explained to them that there are two versions – a one drop that was done earlier and this one that was cut later that went into the charts.

I did the first one for Joe Gibbs and then the second one when they wanted to recut it. I said if I was going to recut it I was going to play it differently because I couldn’t just go back and record the same thing. So I played straight four cong-cong cong-cong. It’s funny because last night we were at the studio playing around two o’clock in the morning and when we listened back to the drum pattern I played somebody asked me if I can put back the roll I did in the Dennis new one! I went cong-cong cong-cong and everybody went “Yeah this is tough”. Then I explained to them that there are two versions – a one drop that was done earlier and this one that was cut later that went into the charts.

Niney has said it was him doing the actual production at Gibbs – can you corroborate?

To tell you the truth I can’t remember exactly. We did the first one when Joe Gibbs had the studio in Duhaney Park. I know it was myself and Lloyd Parks and Touter Harvey from Inner Circle did the first version. The second version was me and Lloyd Parks, Bubbler playing keyboards and I think Bo Pee played guitar. Sometimes there are so many people in the studio you don’t know what happens after once you lay the rhythm track. You lay the rhythm and you’re gone.

Just like when I was doing Punky Reggae Party. We’d always leave one studio and check through because everybody is friends and Flick said “Lee Scratch is looking for you. He has this song Punk Reggae Party and he’s trying to get it done but it just won’t come out right. Everybody has tried a lot of different drummers on it”. So I said “What am I going to do if all these don’t? I don’t know what to do!” So I went straight in to record and then I listened to Bob’s voice because on the tape it was only Bob singing. When I did it Flick called Lee Perry and said “Sly did it and he’s gone” and Scratch said “What??” and Flick said “Sly done and him gone up the road”.

> Peter Tosh was the one who really took myself and Robbie international <

You recently contributed to a new book on Peter Tosh, Remembering Peter Tosh – what is your enduring memory of him?

Peter Tosh was the one who really took myself and Robbie international – out there so people could actually see us on a stage playing and not just in the studio. I’ll never forget that. He also gave us a lot of freedom to play the music with him. He didn’t say “You have to play like this” or “You have to go like that” and we thank him for that because this is where me and Robbie developed a lot of ideas from the freedom we got.

Let’s talk about Ini Kamoze - should he have stayed with you and will you work with him again?

Ini Kamoze was a great artist and sometimes you have to move on. But we would work with him again because he is a great songwriter and he has great melody and there is something about him. When I heard the tape Jimmy Cliff gave me to listen to and I heard his voice and the song he was singing I gave it to Robbie and said “Don’t listen to it until I get home”.

Immediately when we started working we cut the six songs same day. All six were cut and voiced in one day and one take. Just his mannerisms and how he writes I really liked. There was a magic that came out of both of us working together. Not to say he shouldn’t have gone on but you know, sometimes, people want to go into different avenues and you have to give them the freedom to try things.

People still talk about his record – even in Jamaica. That reggae revival that you were talking about – it’s him and Black Uhuru they are listening to. Because those are the two mainstream artists that we gave a definite sound and shape so you could go back and put on your record and be blown away that you’d never heard this before. We’d done work the Tamlins and Peter Tosh but this sound was different. Everybody had a distinctive sound.

SLY’S TOP DRUMMERS

You were recently named as number one in LargeUp.com’s list of the top ten reggae drummers. Who are your top ten reggae drummers?

Really? Where was that? I think sometimes most people don’t go back far enough and check around. If I am going to talk about drummers I will tell you the greatest drummers for me.

- Lloyd Knibbs is the godfather, right?

- There is a drummer called Joe Isaacs, a lot of people don’t talk about him. He was good because he played on a lot of songs that people didn’t even know he played on like Johnny Nash Hole Me Tight and a lot of songs at Studio 1

- Fill Callender

- A drummer by the name of Bunny Williams who played for Studio 1 – he’s wicked

- Horsemouth – Leroy Wallace

- Carlton Barrett is wicked

- Hugh Malcolm is wicked

- Drumbago is wicked

- Paul Douglas who used to play for Tommy McCook and the Supersonics and is a wicked drummer

- You have Winston Grennan he is wicked

- And there is also Tin Leg he is in there

- And there are one or two drummers who didn’t play a lot of sessions like Mikey Boo – great drummer

That’s 12!

All of these people I respect so much and I learned so much from all of them. When I was coming in to play I used to ask myself “What can I do?” because these are some great drummers and they have done everything.

But what I started doing was listening to a lot of African music and looking at people’s body language and I started playing the drums like what I would think of. I would always look at beats from when I was little and I used to look at my mother. I’d sit down and look at the creative dancing thing. They would play and people would move their body and I thought “This is the key”.

But all the drummers I’ve mentioned – all of them are number one for me in my book. I respect them so much.

Fill Callender recently received the Order of Distinction. Would you like to receive such an award?

(laughs) If I get an award I’ll take it but I’m just about the music going into people’s houses and them enjoying it. Getting a hit record in the charts in America or somewhere and the music moving forward and people outside in other countries playing reggae.The award? It’s all right. If I get it I’ll take it but that is not on my mind. Because anybody could get an award and they’re still not moving the music so I prefer to be a part of that movement of the music. Moving it into different areas and developing it so people could say “That’s nice. I like that”. I feel better sometimes when someone says “I like that”.

Like this Taxi Gang album we are putting out – it’s so different. But it’s simple and straight forward and anybody could get into it. Because everything is the people and what they like. If they don’t like it… well you have to go and try again. (laughs)

Thanks

Thanks so much for doing this interview. I enjoyed it so much it didn’t come like an interview – it was like we were just sitting and reasoning about the music.