Steel Pulse ADD

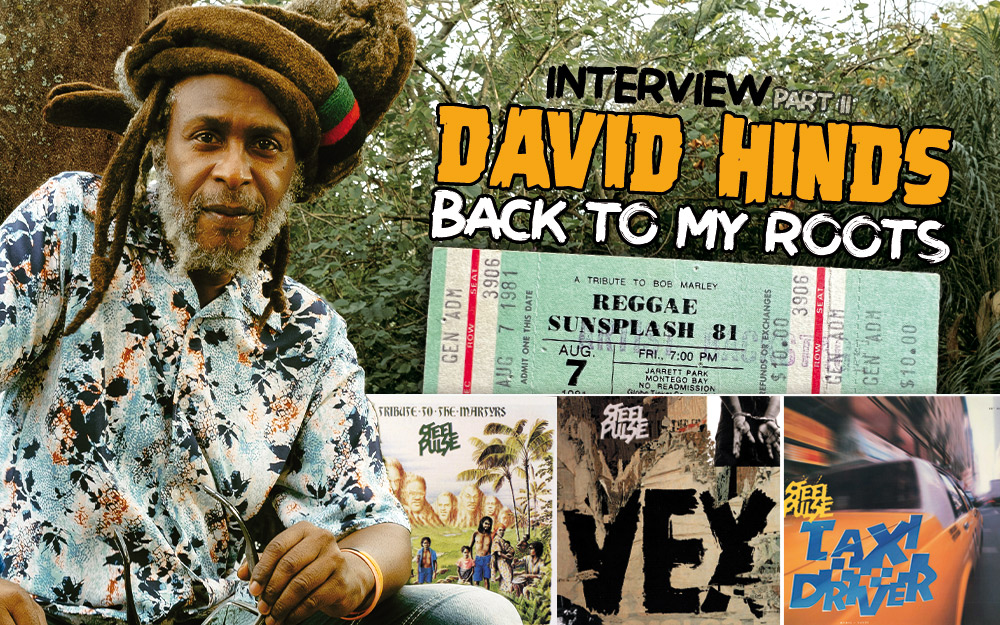

David Hinds Interview Part II - Back to My Roots

07/22/2024 by Tomaz Jardim

In this second installment of the interview [read PART I here], David Hinds reflects on the inspiration behind some of Steel Pulse’s greatest work, while also discussing the band’s perilous search for enduring international success - a search that temporarily drew Steel Pulse away from its roots and distanced it from some of its most loyal fans.

We tend to think of the exportation of reggae from Jamaica to England, but of course Steel Pulse did this in reverse, taking British reggae and playing it on numerous occasions in Jamaica, including at Sunsplash. What was the reception of the band like in Jamaica?

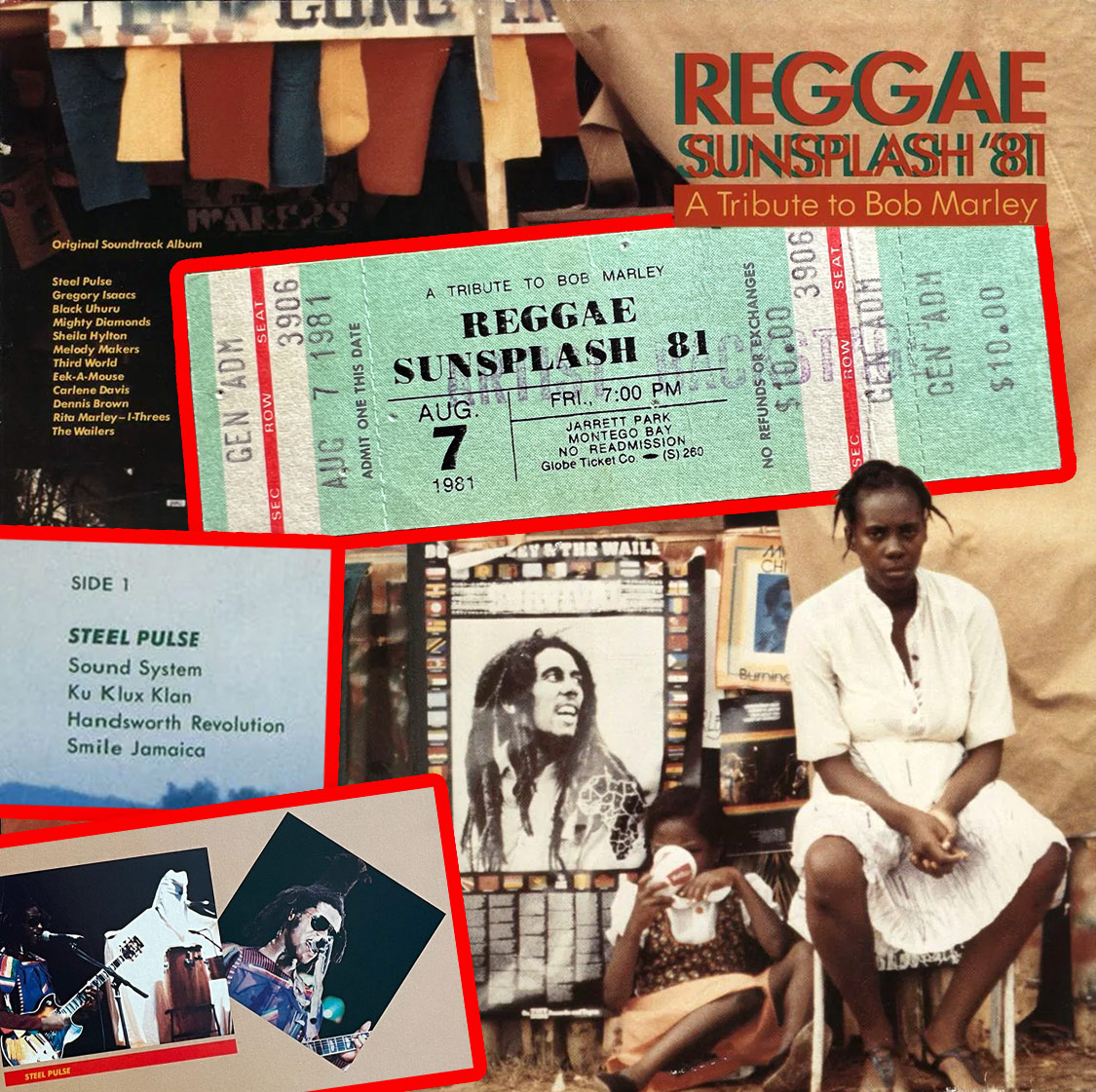

Well our feeling the very first time we played in Jamaica was that of apprehension and nervousness because of how we were treated back in our own hometown where our peers never thought reggae from Britain was credible. So we said, "If they’re thinking that, and most of them were born here like ourselves, what are the Jamaicans living in Jamaica, where the music originated from, going to feel about it then? Are we going to be booed? Are there going to be bottles thrown at us? What's going to happen? Are they going to just walk out?" We didn’t know what to expect. So we did our first Sunsplash at a place called Jarrett Park in 1981. Bob Marley was in his grave for about two months, if that. And we did the show and the reception was tremendous. And we said, well, why is that? And the sense among the people was, "You're the first reggae band from England that came here and sounded like yourselves. You weren't trying to copy us. You weren't trying to sound like us; you guys sound so different and we like the way you're sounding; everybody else comes trying to sound like us."

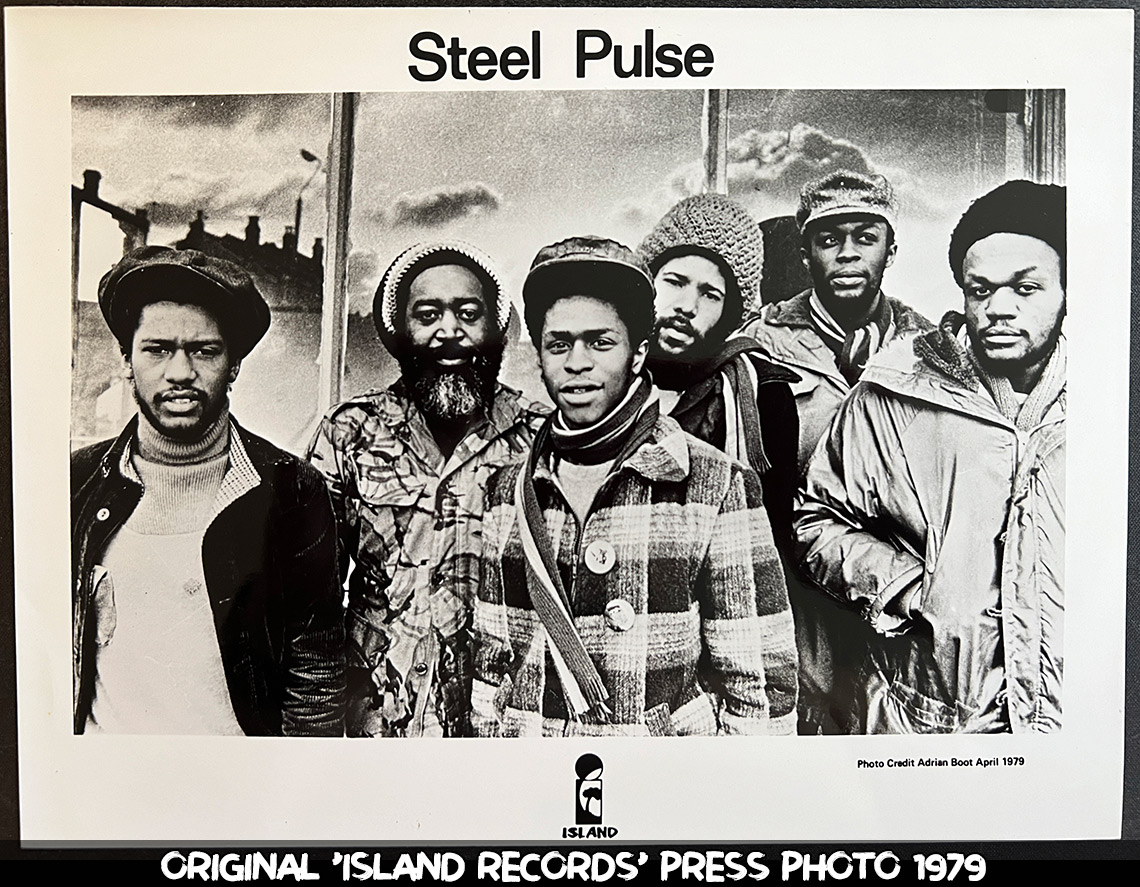

And really, a lot of British bands went to Jamaica and didn't get the reception we did, because they went there trying to emulate what a Jamaican band should sound like. And back in Britain, that was the thing to do: The closer you were to the Jamaican sound, the more you get accepted in your community. I mean, that was one of the reasons why Aswad opened for Burning Spear and why they backed him when he first came to England in 1977. The feeling was that the closer you can get to being affiliated with someone who people would see as the ‘dapper don,’ the more you’re going to get accepted. And in all honesty, if we had the opportunity, we would have done the same thing, but we didn't have the opportunity, and I'm glad we didn't. Because for a few years right after that, Aswad weren't recognized for quite some time because they were then seen as a backing band. So it really didn't do them any favors in the end. And at the same time, people were starting to ask after us, "Who are these guys?" So it was like a double whammy for Aswad. All of a sudden, we're getting recognized, and everyone was turning up at our shows, and we got signed to Island Records in 1978 with our first single Ku Klux Klan. So that is how quickly things were happening back in those days.

I want to ask you about your songwriting and the things that strike me as unique about it. Your songs address a lot of immediate political events and injustices, be it Trayvon Martin or George Jackson or the KKK or climate change. And one thing I’ve noticed is that you often insert yourself in them and write from the first person, which helps to give them an emotional depth and power. In ‘Biko’s Kindred Lament,’ for instance, it’s not just about Biko’s murder, but how “the night Steve Biko died I cried;’ in ‘Ku Klux Klan,’ we also see things through your eyes: “walking along just kicking stones and minding my own business,” or more recently in the song “Don’t Shoot,” we look out from your eyes, as you sing “I’m choking, I can’t breathe”. Does placing yourself at the center of these songs lend them greater power?

I've never really looked at it like that, but you're absolutely correct as far as not seeing it from a third person's perspective. I think my upbringing has something to do with that. I was exposed to the news a lot with my father and exposed to all kinds of scenarios when it came to movies. And one common thread with me watching these movies, me reading the newspapers, me watching what's going on TV, was always imagining, well, wow, what if that was me? As a kid growing up, for example, we'd switch the TV on and we'd see black folks fire-hosed in America during the civil rights movement, and dogs. As you know, in England, none of that was going on, where dogs were biting at you and being hit with truncheons - none of that was going on in Britain. There were animosities, but not at that kind of capacity. And so as a result, I was saying, well wow, what if that could have been me? And I remember things my father said that have stayed in my head, like the day Malcolm X got assassinated when I was eight going on nine. And I remember him clearly saying he knew that was going to happen. He felt it. He felt they were going to get this guy. Because as far as my father was concerned, your Muhammad Alis and your Malcolm Xs, your Martin Luther Kings did no wrong. They were seen as the way to go to get our liberation as a people. So I sort of held on to the shirt tails of that kind of sentiment, you see what I'm saying? So I didn't really look at it the way you did just now, where I sort of did away with the third party perspective and had me within the mix of things, walking around minding my own business, “don't shoot”, all that. I never really looked at it like that. But I can only believe that's where it stemmed from: Me always feeling, well, that could have been me.

I remember this one movie that really made an everlasting impression on me: Imitation Of Life. It was about a black woman who was a maid, and she had a child who came out so light, she passed as white. And the kid loved her mother very much, but as she got older and saw what society was like, she decided to distance herself, and the mother couldn't understand why. In the end, the mother started to accept that her kid was recognizing that she was more a part of the white world than she was of the black world, and that she was getting more favors being a white person and was more accepted as white than black. And years later she was working as an actress in a play and the mother came to visit her after a long period of time not seeing her. And when she knocked on the door, the people that were working with the daughter said, "there’s a woman out here, a black woman that's come to see you." And she didn't know what to do, because, what's a black woman come to see her for? And she had to introduce the mother to her coworkers - revealing that she was just a maid who had raised her when she was a little girl. And the mother saw what was going on and accepted that that's how her kid saw her. The mother sort of played along with it just to let the kid feel, you know, comfortable. In the end the mother dies, and she's in the black community and her coffin is drawn through the streets by a horse and a cart. And this is when the girl breaks down and regrets everything and all the ways she treated her mother over those years. These are the movies that played on my mind.

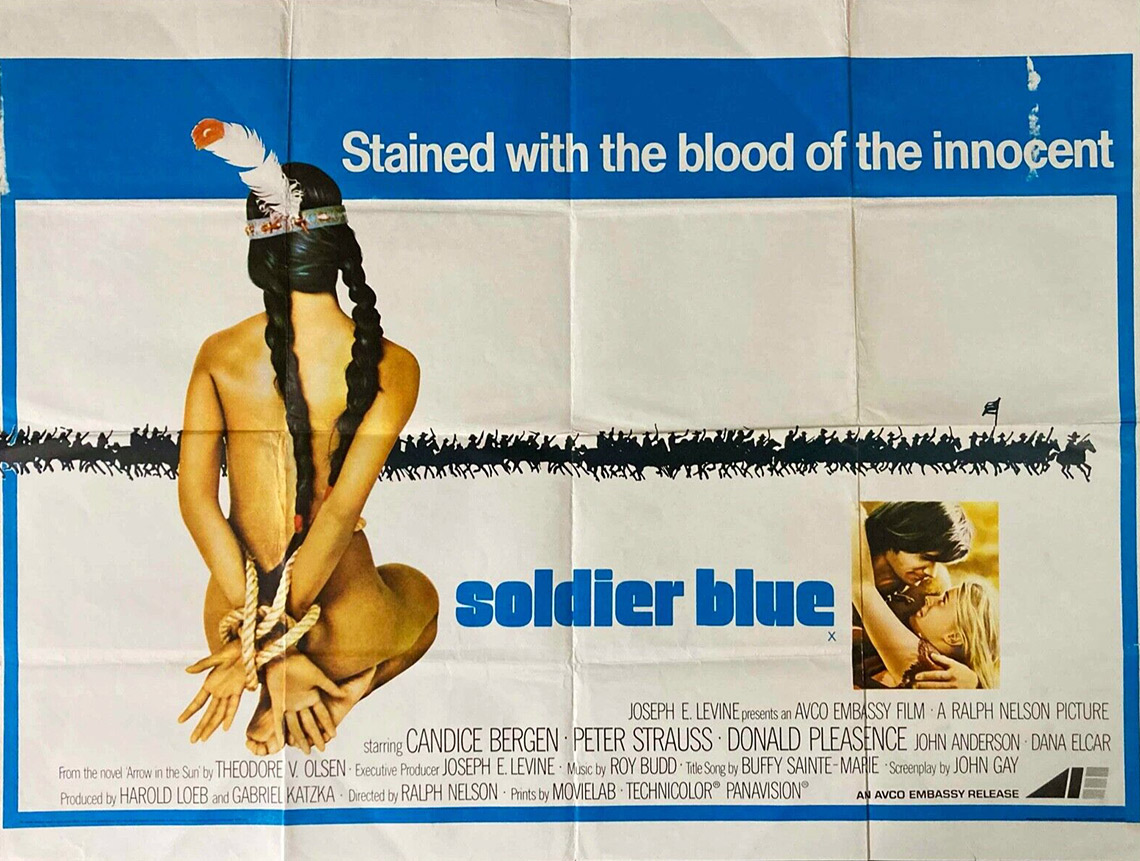

Another movie that played on my mind as I was growing up was called Soldier Blue, starring Candice Bergen. And that movie had such an overwhelming effect on my mind that it was the key reason why I wrote the song Soldiers. It was all about the American US Cavalry slaughtering a whole shebang of Native Americans. And Candice Bergen, throughout the film, was trying to tell the soldier, who was all for the slaughtering of these Indians, that it was the wrong thing to do. And towards the end of the film, he started to catch on to what she was trying to say. And that's how songs like Soldiers came into play. So the answer is yes, I have this tendency to go about writing based on things I've experienced and kept saying to myself, well, what the f---, that could have been me! Steve Biko, that could have been me! You know, so that's how I sort of looked at things and still do as a matter of fact.

There's a complexity to the sound of Steel Pulse that one often doesn't find in reggae, especially in terms of the arrangements. I think, for instance, of “True Democracy” or of “Tribute to the Martyrs,” and the layers of sounds, right down to the little percussions. And the production is so gleaming and bright. To what extent were those recordings the product of the band’s vision versus perhaps the vision of a producer? Because to my ear, there are not many records that you can put on that level. They really exist in a world unto themselves.

Well, it's a bit of a juxtaposition, really, and a conglomerate of things happening at the same time. And I could say this: if I turned the clock back, half that stuff you're talking about, I wouldn't do it anymore. I wouldn't do it! The percussion layers, the chordal complexity. I think as times go by, the only way I can give you an example of what I'm talking about is this: I remember attending the Grammy Awards back in the 80s where there was Mark Knopfler from Dire Straits, another guy called Hank Williams Jr., and a number of other guitar players all jamming on stage at once. And it was just a wall of noise. I couldn't see the leaves for the trees. I couldn't hear, it was just a wall of noise to me. Then I heard something, and I said, “that's BB King!” And I recognized him straight away. And I says, damn, all BB King played was one note. And you felt the seasoning of it, you felt the energy of it, and everybody else was just like a wall of noise. ‘Look at me, watch how fast I am, watch how many notes I can play in a second.’ And then this guy comes and plays just a few notes, and that stuck with me.

So I've got this thing where I believe things could have been done a lot more simply, but we were trying to impress ourselves and impress the world with a new and a different approach. I also at the time attended art college for a few years, where the kind of guys I was hanging out with were all exposed to jazz rock. So there was acts like Stanley Clarke, Lenny White, Al Di Meola, John McLaughlin, on the drums Billy Cobham, Jerry Brown on drums as well, Eddie Martinez on guitar, and all these guys were playing their instruments at a million notes a second. So it became like sophistication, it became like that's where it's at. The chords that came in as well, they weren't regular chords, they weren't regular B major, go to D minor and all that kind of stuff. It was all about, you know, B7b5, and D6m5, and all those kind of chords. And we were saying, ‘damn, so if I could figure this kind of chord and put it into reggae, it'll give reggae a different approach to what I normally hear and see.’ But not realizing, ‘but wait a minute, David, you haven't really gone through all the rudiments of what basic reggae is about. Why are you taking it to the level where you're taking it, where you want to add all these weird chords, seven flat and fifth chords, and 11th chords, and augmented ninth chords. What are you going to do all that for when reggae is not about that?’ We just thought the music needed to have that kind of approach, and hoped that our message got into the equation at the same time.

So this is where we started to butt heads with the producers now. And it was Karl Pitterson who recorded our first album. And that was butt heads galore. It's like, "What? Who are you all the way from Jamaica trying to change our sound? We know we've got a sound here." And he's saying, "Guys, I'm not trying to change your sound. I'm trying to improve on it. You don't have to do it like that. Do it like this." And we're going, "This is how we want it." And after a few weeks, we had to compromise with Karl on who did what, who's supposed to do this and that and the other. And we ended up with the album Handsworth Revolution. And it took a few years after that to realize, well, wow, had we listened to Karl, and simplified that part of the song, or this part of the song, it would have been a stronger song than what it is now. And it took a few years of seasoning, a few years of being more experienced working in a recording studio, a few years of learning how to communicate with other people that see your thing different - and a few years of also learning your ability to really perform as an artist - that made me look back now and say, ‘hey, wait a minute.’ So when I look back on my career and those albums that you mentioned, all I can think of is shoulda, coulda, woulda.

Wow, I don’t think “True Democracy” and “Tribute to the Martyrs” could get any better!

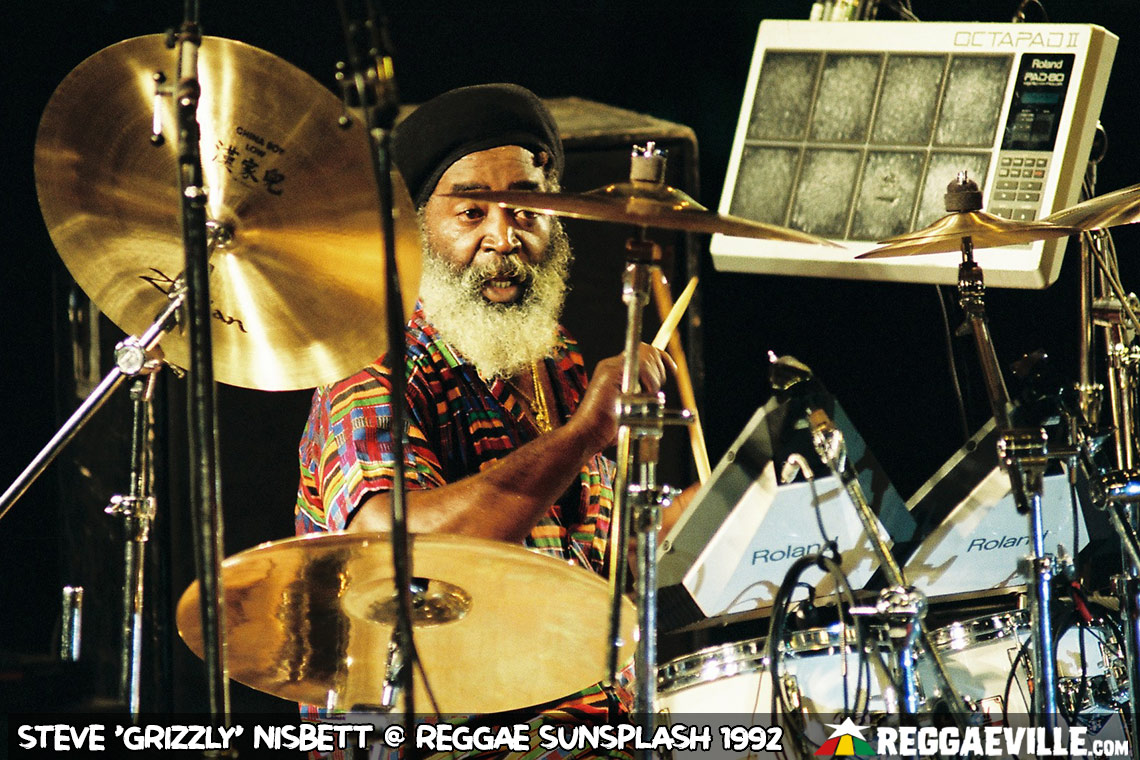

Well it’s funny you should say that, because Grizzly, our drummer that passed away six years ago, felt that. Out of all the albums we did back then, Grizzly's favourite album was Tribute To The Martyrs. And it's the one that, every time I hear it, I sort of cough during the conversation or something like that, or you know, excuse myself to go to the bathroom, that kind of thing. Yeah. And it was all because it had all the bells and whistles of what you said you sort of like about the Steel Pulse sound at the time. And Grizzly, every time they asked him, "Which is your favorite album?", he pointed to that one every time. And after a while, I started to accept it. Because what you have got to remember as well, when Grizzly started out as a musician, he was not in the reggae genre at all. So he was simply looking at music from music's perspective, as opposed to whether I like reggae or not. It was like, is it good music? Is it bad music? Do I like this music? And that's how he was looking at it. So put it this way: I've grown and seasoned myself and am still in the process of seasoning, where I sort of look back on the old school way that we did things and still try and take a bit from it and see what we can still use and still formulate for the Steel Pulse that's growing as far as creativity. Because that's important to me at the end of the day. Where we're not stuck in a rut, but we still have the ability to hold on to our fans based on what they liked, you know, from the days of yesteryear.

I wanted to ask you about a tune on the album “Vex,” called “Back to My Roots,” where you sing ‘searching for fame and gold/we gained the whole wide world/ and almost lost our souls/ got brainwashed by the system/what a heavy price we paid.’ And it seems to me this is a pretty remarkable piece of self-reflection about the journey of how you guys have evolved as a band but took some traumatic turns in the process?

Well, let me tell you why that song was written in the first place. Reggae and the artists involved weren't getting their fair dues within the industry, as far as popularity, record sales, the whole thing that it takes when it comes to being in the pop genre, R&B genre, rock genre, and we said, ‘hey, wait a minute, people turn up at our concerts, but ain’t nothing happening with us. We're still driving a bloody Toyota, where Joe Blow is driving a Range Rover. What's going on? So a lot of the reggae acts around that period of time, in the 80s, started commercializing music. We tried all kinds of ways to let the music be acceptable by the industry.

So that was a self-conscious desire?

Yes, it was a self-conscious decision. Don't let anybody fool you. It was the same with everybody. They're looking at it and they're saying, ‘look, there's money to be made, we're not making it. Why?’ And we sat down and we said, ‘well, this is the reason why. Well, who's going to want to listen to that? All you're talking about is Jah Rastafari all the time. Nobody else knows who Jah Rastafari is.’ So that, now, no longer became a subject matter if you want to make a commercial hit played on the radio, with everybody going dancing to it. So we saw at the same time that there were songs that were recognized the moment they were played, and the band became popular or commercialized. Bob Marley’s Could You Be Loved, for instance: you go to nightclubs, it's playing; Third World, Now That We've Found Love. So everybody's saying, ‘well, it seems as if every time these guys do songs like that, it's where it's at.’ So everybody tried to do little things to the best of their ability. Freddie McGregor did it. Aswad did it with Don't Turn Around and who else, Jimmy Cliff - you name it. The only two bands that never changed the way that they did their music were Israel Vibration and Burning Spear.

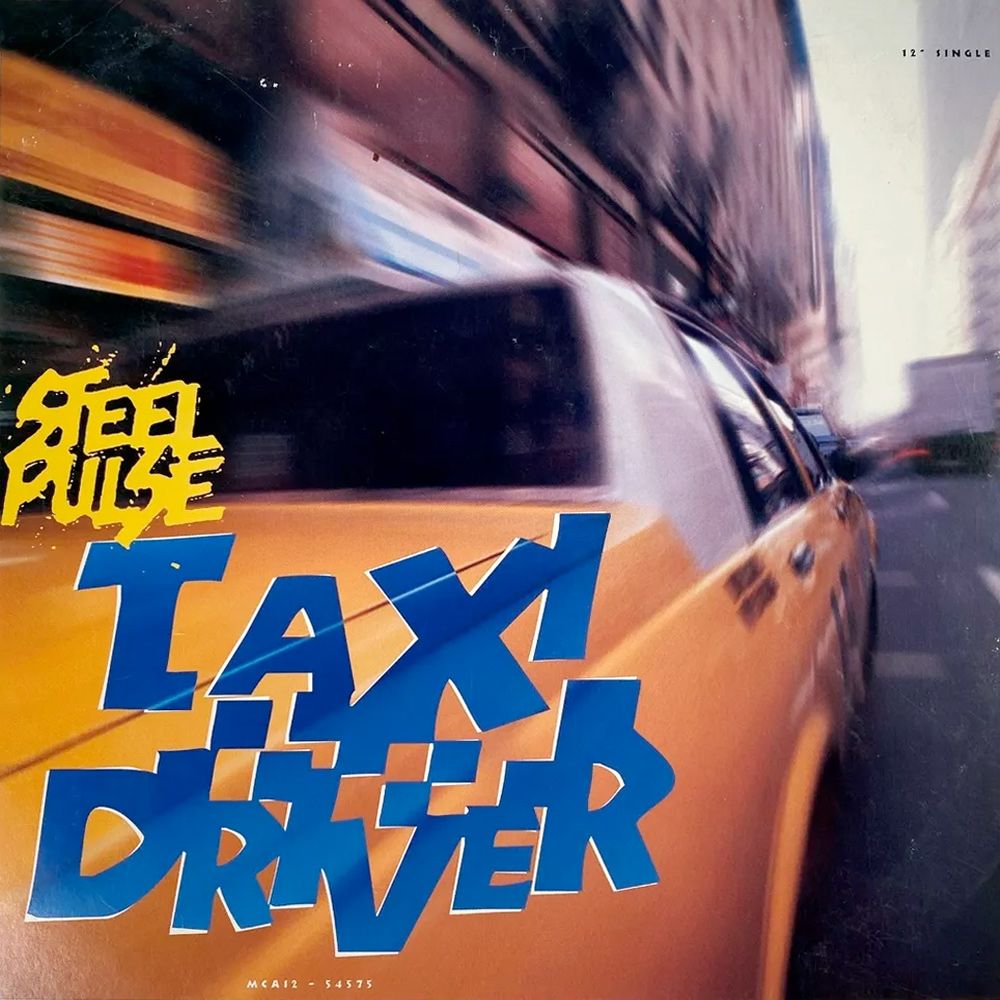

And we got crucified for doing it. All of us did. Our fans were dropping us like hot potatoes. Once we started, you know, tracks like Hijacking, Don’t Throw Me Out Of The Disco, what the hell is that? Steal A Kiss, Schoolboy's Crush, all these little songs I was starting to write, thinking maybe if I write this, some other R&B act could adapt to it, and it could find itself in a film. We were looking at it along those lines, but it never happened. And this is what the record label kept putting in the equation, as if the reggae music that we were doing was not going to cut it unless you had it sounding like this or sounding like that. So we went and we did an album called Victims, with Taxi Driver on it. And we had a track on it, Get You Out of My System, written with Stephen Bray, who was Madonna's producer at the time. And there was another song called Soul Of My Soul, which had Family Stand, a well-known R&B act on that. The record company wanted to give us producers - like ten of them, and asked who we could work with. And we said, well, we did like Ghetto Heaven by Family Stan didn't we? And Madonna was a success, and so we decided to go out there with Stephen Bray. And the record label advanced more money to us. And at that time, these producers were demanding a lot of money for their production. And then you've got guys that were mixing albums that were getting about seventy grand just to mix a track.

And after all of that, none of those songs gained us any traction, and instead, it was our production of our track Taxi Driver that made an impact. And people liked the political sentiment behind it - "Taxi driver won't stop for me.” And before you know it, the news media across the United States jumped on it, especially in New York. Cabs weren't stopping for black people. And we'd be getting interviews from journalists.

So after all of that, and once the dust settled, we're looking at what the hell happened in there. We lost our fan base, and we're out with all these lollipop type songs. What the hell's going on? I said, "You know what, no, this is the last time I'm doing any tracks to suit the record label. Screw you all, I’m not interested, I'm going to go my way." And that's how that song came into play.

Read PART III here: David Hinds provides his insights into some of today’s most pressing social and cultural issues, and contemplates what the future has in store for Steel Pulse.

Read PART I - THE BIRTH OF STEEL PULSE here!