Steel Pulse ADD

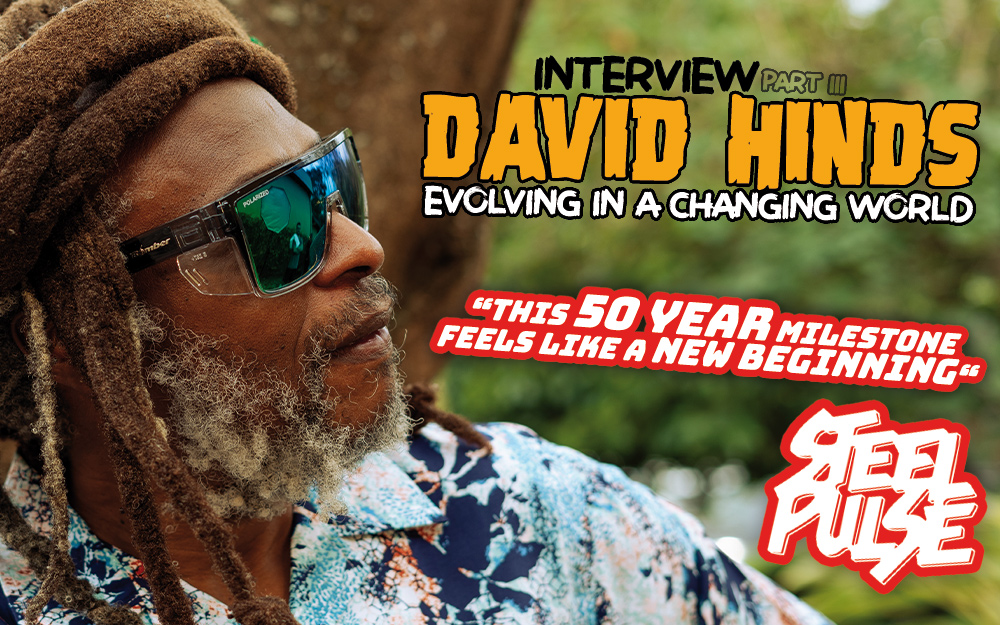

David Hinds Interview Part III - Evolving in a Changing World

07/30/2024 by Tomaz Jardim

In this final installment of the interview, David Hinds provides his insights into some of today’s most pressing social and cultural issues, and contemplates what the future has in store for Steel Pulse.

You tackle so many sensitive social and political issues in your songs. I wonder if there are ever things that you find are just too difficult to put into song? Like things that you think are important, but ultimately that you just find too challenging to adequately encapsulate?

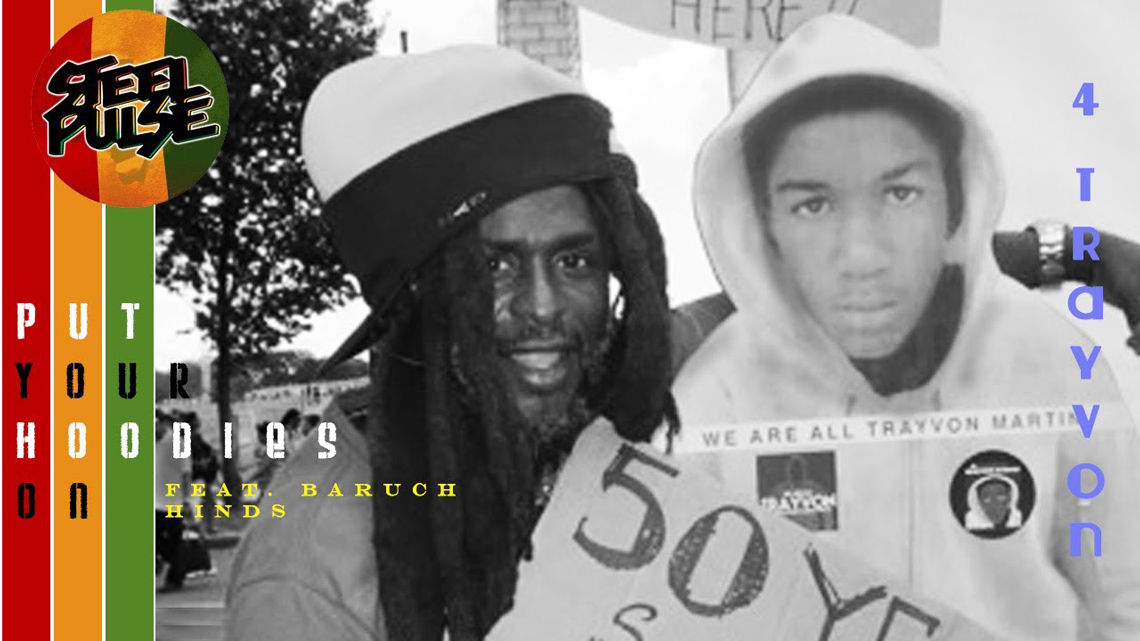

That's a very good question! I like to know that I'm current when it comes to issues. And what I've learned over the years is that there's certain things you just don't talk about, or if you do, you do it on a superficial level, or you just simply skip the subject altogether and hope that it never comes up. We've done songs that address racism in the United States, which as you know is sort of our stomping grounds. And I remember writing a song called Put Your Hoodies On, which was about the Trayvon Martin incident, and then we went back and wrote Don’t Shoot which was based on the Michael Brown incident in Ferguson, Missouri. And we'd be checking our mail and our social media platform and saw the odd piece of hate mail. You know, ‘don’t come to Charleston, South Carolina or else!’ and we'd say, wait a minute, what’s this going on? And apparently there's a lot of people amongst our fan base that we thought, as lovers of reggae, would be all behind obliterating racial tensions and about unifying the world. But we find that, a lot of times, it's just as far as it goes. ‘We like the music, but stick to what you do. Don't start coming to our politics,’ and all that kind of stuff.

So I had to be watching what I had to say on a racial level and although I still delve in and try to use the clever art of songwriting and playing on words to make it happen. Religion is another thing that I’d really like to drive home, which I’ve realized I've got to be iffy about. For me, it's a sucker’s game. I look around and all the preachers have all got Rolls Royces on their front lawn. So where's that collection box going every Sunday? So I've got this thing about religion, but it's a very touchy subject. The sun shines out of the preacher man's ass, if you see what I'm saying. I was in Ghana just last week, and I've seen what religion has done to Africa. At the very end of the day the truth be known as far as I'm concerned: it's the church that's making the money and the people that don't have the money. They think that they're all forgiven if they keep donating. I'm saying, wake up! And someone said to me, "Dave, you go tell anybody what you want to say about religion, you might not live to see tomorrow!" Because there's people that are so hell bent in their approach and the way they've been steered in the direction of religion that it's taboo to have it as a discussion.

There's another situation as well, where as a Rastafarian, I've evolved. When we started out as Rastafarians, its philosophy had a lot of facts to it. But as I grew into the whole movement and dissected each aspect of it, I've learned that not everything went the way I was initially taught. Therefore, I have to be careful with whom I discuss those kind of conversational pieces with, because you've got some people that are regimental in how they were raised as Rastafarians, and have not really seen the world on an international scale in the way that I have. I mean, I've come from a period of time where guys were burning the Bible. I've come from a period of time where if I'm having lunch with someone, they dare not be there cutting into meat, especially pork, in my presence. This is what I'm saying. That's how it all initially was back in the day. ‘What? And you're going to eat that in front of me? Who do you think you are?’ Like I said, I've grown. I've gone to certain countries where people could eat an insect because it's going to be their only meal for the day. And I said, there you are, criticizing someone or pointing the finger at someone because they ate the slice of pork in your presence. What difference does it make, Dave? You're not eating it. It's not your thing. So I've sort of learned how to evolve.

Can I ask you about something that may be even more controversial? What do make of the increasingly contentious issue of homophobia in the context of Jamaican music and dancehall? Does that count among those topics too difficult to address?

It's a very good question. Yeah, right now, when it comes to homosexuality, when it comes to the black race, whether you're in Jamaica, or your community in England, or among the billion-strong populace of Africa, homosexuality is a no-no. Right? And it's based off religion. Our religion has been taught where people say, well, ‘Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve.’ So that is what religion has done. So, generally speaking, they have that kind of a mindset. So you'll find your Bounty Killers, your Beenie Mans, your Buju Bantons, you name them, and when it comes to homosexuality they can’t tolerate it at all. When it comes to me now, I'm more of a realist as far as the way the world is going. Now, not everything in the world I'm going to be in favor of, but I've got to understand that the world is changing around me. I remember growing up as a kid where you could not announce to anybody that you're illegitimate. In England they would say, ‘oh, he’s a bastard’. Because being a bastard in England was like a no-no when I was a kid growing up. Now, nobody gives a toss if you're illegitimate or not. So it's telling me that the world is growing, so learn to grow with it.

So I see more important issues in this world than someone's sexual preference. If it’s the wrong thing to do, or the right thing to do, at the end of the day it’s going to be God’s decision. I'm here to address issues that I think that are important to me, and to where I think my people need to be. So, I've learned to see where the world's going and ask, where does it really affect me? I mean, I've got a friend within the industry whose daughter decided to have a sex change and he didn’t know what to do. He's bewildered. "What do I now David?" I says, "Well, you know, call him by his new name." That's what I was suggesting, you know, and years went by, and he says, "Well, David, it’s working, you know, I've got to get used to it." So yeah, I'm not saying I'm accepting everything; all I'm saying is that the world is changing.

A year or two ago, I paid a visit to the Dr. Martin Luther King museum in Memphis, Tennessee. And I went there with a worker that I had with me. And on the way out, it was all about buying memorabilia and souvenirs and all that kind of stuff. And all of a sudden, he sees all these LGBTQ little trinkets and stickers and souvenirs for sale, and this is in the Dr. Martin Luther King museum. And he was livid! So he said, "Martin Luther King would never have stood for all this stuff!" I'm saying, "Hold on, how much do you know about Dr. Martin Luther King?" And he didn't know that much - just that the civil rights movement came to liberate the people. But what he didn't seem to realize was that Martin Luther King wasn't about just liberating black people. He was about liberating people, period. So I said to him, my hunch is that if King was alive today, he would have tolerated that and moved on because it's a victimization of other people. And he opposes all forms of victimization. So although he's a preacher man that says 'Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve', I truly believe that he would have embraced the fact that there's such a reality out there and moved forward. Because like me, he had bigger fishes to fry when it comes to human harmony. Because at the end of the day, that’s the most important thing. We're looking at wars right now. If you look at the paper, there's ongoing wars all the time, for ridiculous reasons. Israel and the Gaza Strip, Russia and Ukraine; in certain parts of Africa there's militias and you name it, it's everywhere. So that's my take when it comes to that issue.

I was reading a recent Linton Kwesi Johnson interview, and he was asked whether he thought things had improved in Britain with regards to race since he first emerged as an artist, and he immediately said, “of course they're better!” Steel Pulse has also been commenting on race and racism in Britain for 50 years – how do you see it now? And do we risk losing our vigilance if we say that it's better in some ways?

No, because there's so many ways it is better. In my neck of the woods when I was young, there were certain streets that I would not be brave enough to walk on at certain times of the day, or certain times of the night, on certain days of the week. You know, like for example, the Villa ground was a football ground a half mile from where I lived. And I always made it a rule of thumb not to be around on the streets when these guys were attending the match or leaving the match, especially if the team lost. Because you don't know what's going to happen if they see a black dude walking on the street. Their team just lost, and here is someone saying "I can't park my car because of you living here, blah blah blah." So there was a tendency, to ask, "What day is it, Saturday? Is the Villa playing today?" Yep, okay, I won't take that road. But these days, I don't even have to think about it now, you see what I'm saying. Well, not as much, because everybody's sort of integrated socially to an extent. I grew up in a period of time where black soccer players were few and far between on the football pitches and every time they made an indentation within that industry they had toilet paper thrown on the pitch while they kicked the ball or banana skin thrown on it. And it was their way of saying, "Hey, we don't care what team you're with – even if you're with our team, you're still what we call a nignog." And that went on for quite some time. That's not so prevalent anymore. It raises its ugly head once in a while, but nowhere near the magnitude as it was.

So Linton Kwesi Johnson is absolutely correct in what he's saying. Plus, other types of minorities have come into the country. So England is now very much a metropolitan melting pot when it comes to society. So in that sense, it's grown. I think the problem back in the day when World War II kicked in, was that Britain never came back to the population and said, well guess what? All that sugar that we have coming in depends on the backs of those laboring in the Caribbean and other Third World countries colonized by Britain. All those bananas you're eating in the shops came from the Caribbean. All those pineapples that you have there came from the Caribbean or came from South Africa. They never sat down and explained to the population that all those beloved goods come through the hard-working exploitations of Third World people. It was never explained to them. And so the Caribbean population was resented.

And so you hear negative comments like, ‘why was Jesus born in a manger?’ Answer: ‘Because the wogs got all the houses.’ You see what I'm saying? So that was the kind of thing we were exposed to. Now if you mentioned that to someone now, they wouldn't have a clue. So, Linton Kwesi Johnson is 110% correct in saying there has been an improvement. Has it improved to the level we want it to? Hell no. But it's much better than what it was 50 years ago.

Now beyond England and Jamaica, repatriation to Africa has been a consistent theme for Steel Pulse. In “Stop Your Coming and Come,” you talk about Lalibela and Addis Ababa and Shashemene; in “Rally Round,” you sing about repatriation as a must. What is repatriation for you?

Well, repatriation stemmed out of us as blacks born in Britain not knowing ourselves. A couple of decades went by where, you know, people were making it clear that you don't belong here. So with all those things thrown at us at that time, we didn't think England belonged to us, so we didn't belong in England. So repatriation, especially with the words of Marcus Garvey which reggae artists like Burning Spear and the Mighty Diamonds echoed in their lyrics, became like a big thing now - guess what, we're all going to go back to Africa. So it was a central principle of being a Rastafarian. So we all adapted this kind of mindset, but we adapted it for the reason that we were tired of the West and the treatment we were getting. We looked at all the people throughout history who got lynched, shot, jailed for many years, your Mandelas, your George Jacksons, your Malcolm Xs, and it's like Marcus Garvey prophesied that we're not going to know ourselves until we go back to it. So we all said we get it and we're all heading back. Now over the years, I’ve grown to realize that sometimes it doesn’t have to be a physical activity – it’s more of a mindset. But physically, I still do believe there needs to be some kind of establishment in Africa. But that doesn't necessarily mean that I need to be there forever, because I'm international, and I believe that the world is international. If I was a multi-millionaire, the first thing I'd want to do is have property on every continent. So that's how I look at it now.

In Africa, there's a lot of potential there. It has a growing economy. Those who literally got up and went there never made full usage of that piece of land at Shashemene, that commodity, because those who actually went there were not business-orientated. They just had a goal, ‘I'm going back to Africa, I don't give a damn. I'm tired of living in England, paying taxes, I'm tired of being locked up by the police, I'm tired. At least I'm in Africa, you know, if I'm going to get anybody locking me up, it's got to be my own color locking me up.’ And so that was the mindset. What education do you have? ‘Little.’ How much money do you have? ‘None.’ What ideas do you have to develop? ‘I don't have any ideas.’ And that's what happened. Now I think the Rastaman should be able to set up shop or have some foundation there in Africa at some point in their life.

But let me tell you something. This time a year ago, I was in the Australias, but there was a lot of island hopping. And I got to an island called Fiji and we were there stranded for two days because there was a storm going on in New Zealand and we couldn't fly. In Fiji I had to keep pinching myself that I was on the planet. There wasn’t any hostility of any kind. Everybody's courteous. Everything was just beautiful. And I wish the world was like that everywhere. So I've learned that there's certain parts of the world where all the tension that the West has to offer simply isn't there.

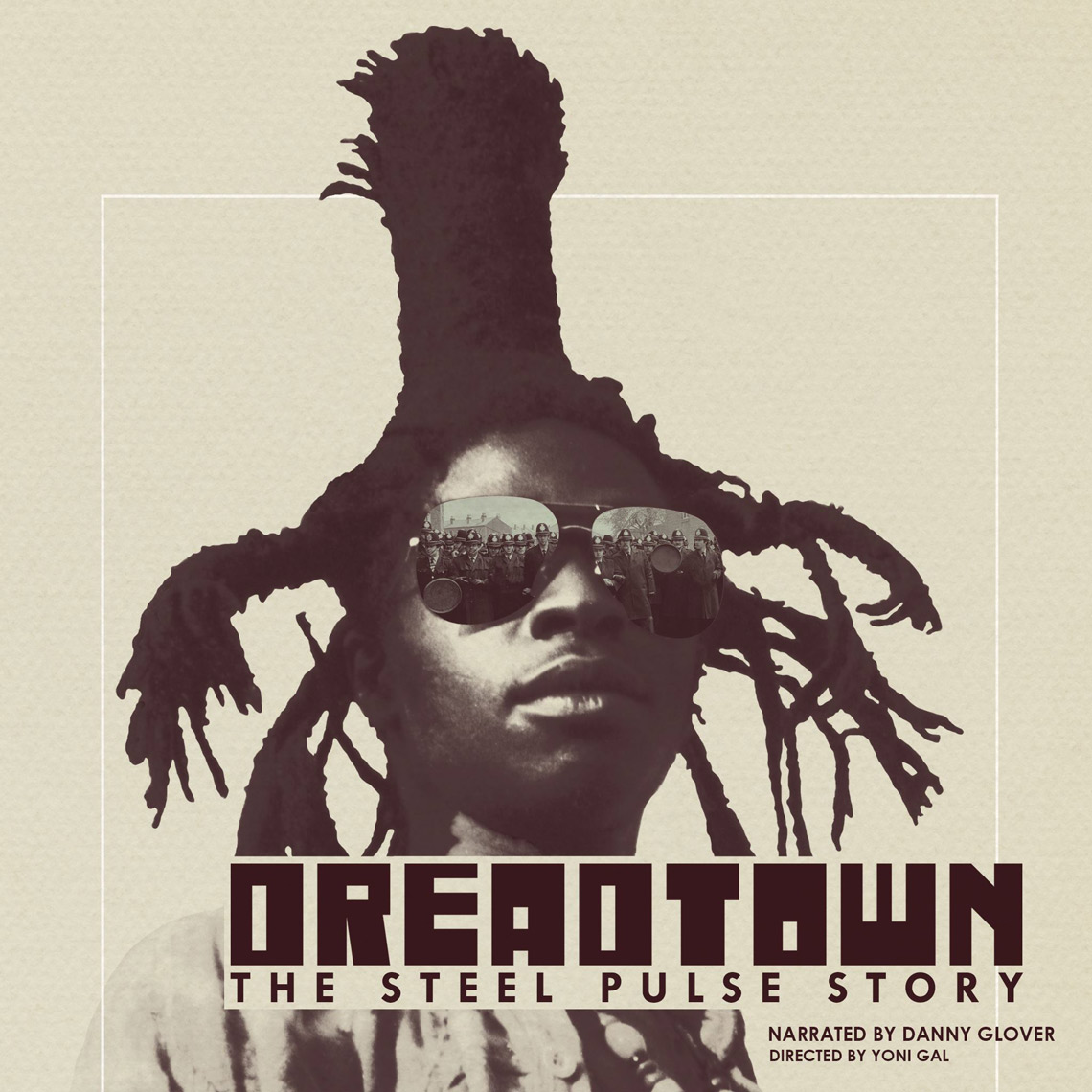

I heard rumblings of a Steel Pulse documentary some years ago – what became of that?

That's another touchy situation. We had a documentary that was supposed to come out a few years ago that was in the making for a good part of ten years on and off. And we had a promising film director that, in a nutshell, when it came to taking the film out there, needed the expertise of producers that could get the film out there, and gain that international acclaim. The problem we had with that director was that he didn't have that experience to complete the film, but he didn’t want to pass it on to someone else who did. And it became like a bit of a stalemate. So that's what basically happened and where it remains. But recently, they called me and want to come back and try and play ball. But my problem is that, hey, there's a lot of things that we said in the documentary there and then, that were relevant there and then, but that might not be relevant now because the world hasn't stopped. So they're saying that they don't think so. We say, well, let's see where it's at. So there might be talks of rekindling that fire and moving forward. We are pissed off because the directors were using our fan base for the GoFundMe aspect of it. So we feel as if we've failed the fans. None of the money came to us. Every dollar went into the film. And there's nothing we could have done with them holding on to it. We've gone into a legal battle in the last number of years, and who knows where it was going to take us. So that's what became of it. But we, as a band, still have a story to tell. And we will continue to do so when it comes to having a different production happening. So we beg the forgiveness from our fans who got engaged in that project - it was nothing of our doing that it hasn’t gotten any further. And if it's not going to satisfy the fans, we don't want to put anything out there. That's how we are. And our fans mean a lot to us.

So let me finish up by asking what’s down the road for you and for Steel Pulse?

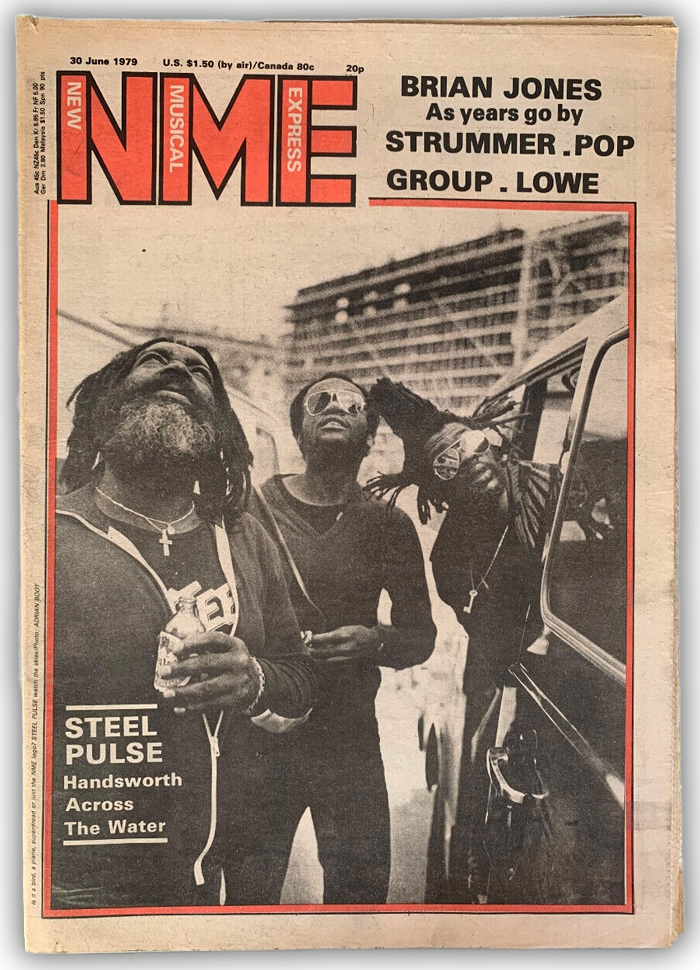

As you know, it's the 50th anniversary. So I can only say that we're going to try to prepare as much things as we can. So when the 50th anniversary actually does come in, there is a wonderful package for people to grab onto and have it as a milestone. A retrospective package as well as probably fresh product. For those people saying, hang on, here's a collection of a band that's been around so long and survived the storm. Ta-da! You know, not many of us can say we've survived 50 years, so that's a good thing.

And you continue to write?

Yeah, I continue to write. I wear different heads when it comes to writing. Sometimes I try and do something that's completely different. Sometimes I try and repeat something, but with a different approach to it. Because once it was written 40 years ago, a kid coming up now would never have heard it. I sort of bob and weave based on what I expect as an audience. I’ll give thanks that we've had several generations that have grown to love Steel Pulse and know Steel Pulse. You know, when someone who’s aged 70 comes along with his grandkids, and they say, "Grandpa used to play this all the time." That kind of thing. I sort of feel good about that. It shows me that we still have a career ahead of us that can last as long as we remain able-bodied. This fifty year milestone of ours feels like a new beginning.

Read PART I - THE BIRTH OF STEEL PULSE here!

Read PART II here, where Davis Hinds talks about the inspiration behind, and production of, some of the greatest records made by Steel Pulse.