Steel Pulse ADD

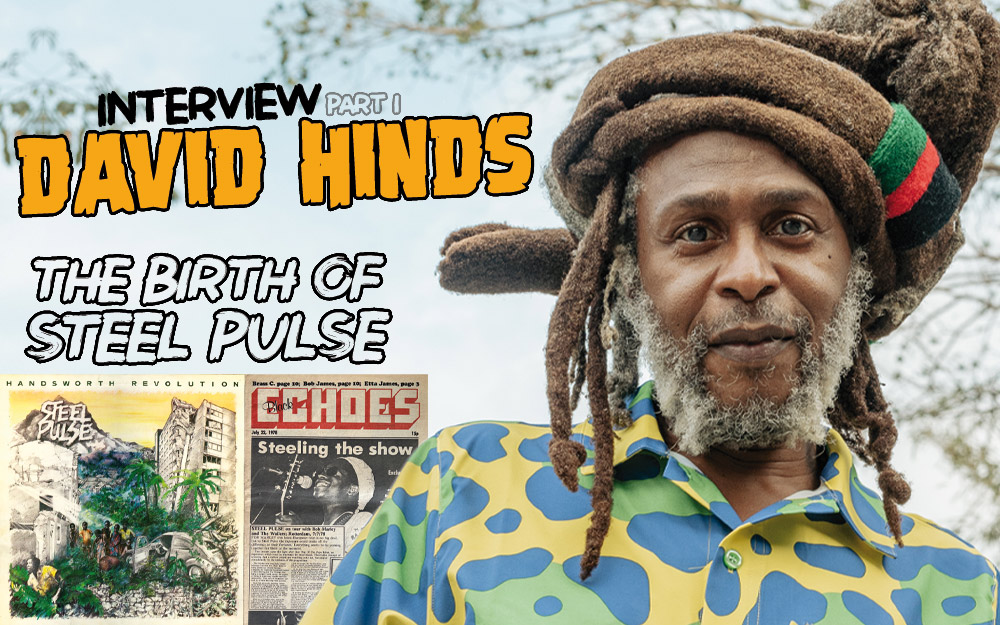

David Hinds Interview Part I - The Birth of Steel Pulse

07/15/2024 by Tomaz Jardim

2025 marks the 50th anniversary of the formation of Steel Pulse in Birmingham, England in 1975. Arguably the greatest reggae act to come out of the U.K., Steel Pulse continues to perform and record music that chronicles the Black British experience and the quest for social justice through the lens of Rastafari. David Hinds, its cofounder, lead singer and primary songwriter, was born in Birmingham to Jamaican parents who immigrated to the U.K. as part of the Windrush generation. Hinds founded Steel Pulse alongside Basil Gabbidon, after the two met as students at Handsworth Wood Boys School. As the band found its footing, it aligned itself with Rock Against Racism, an organization of artists determined to stand up to the racism of Britain’s growing far right political movement. As part of this camp, Steel Pulse gained popularity opening for punk acts such The Stranglers and The Clash who were similarly aligned.

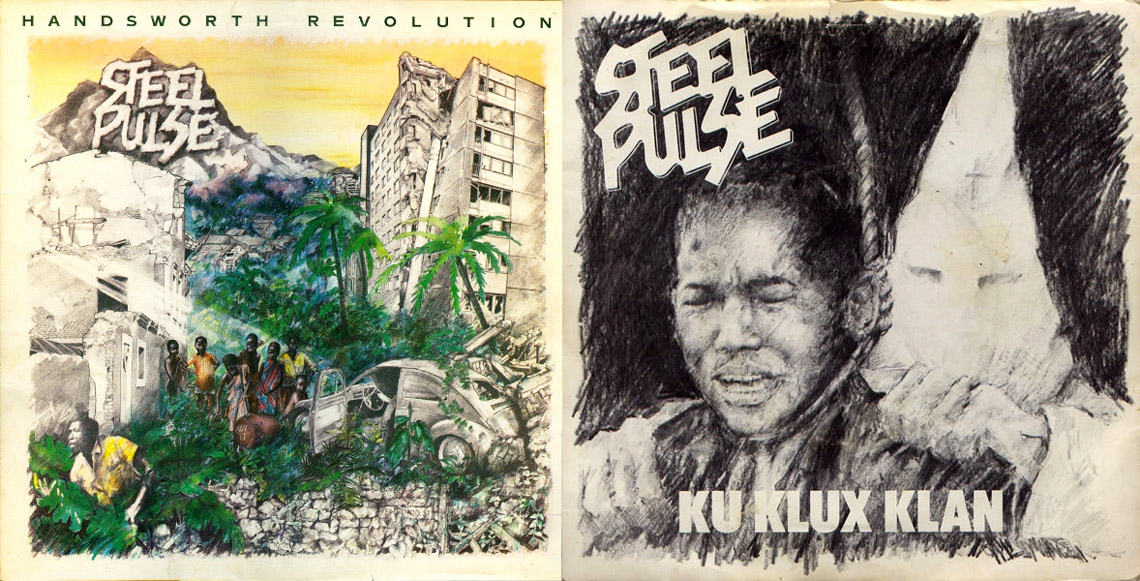

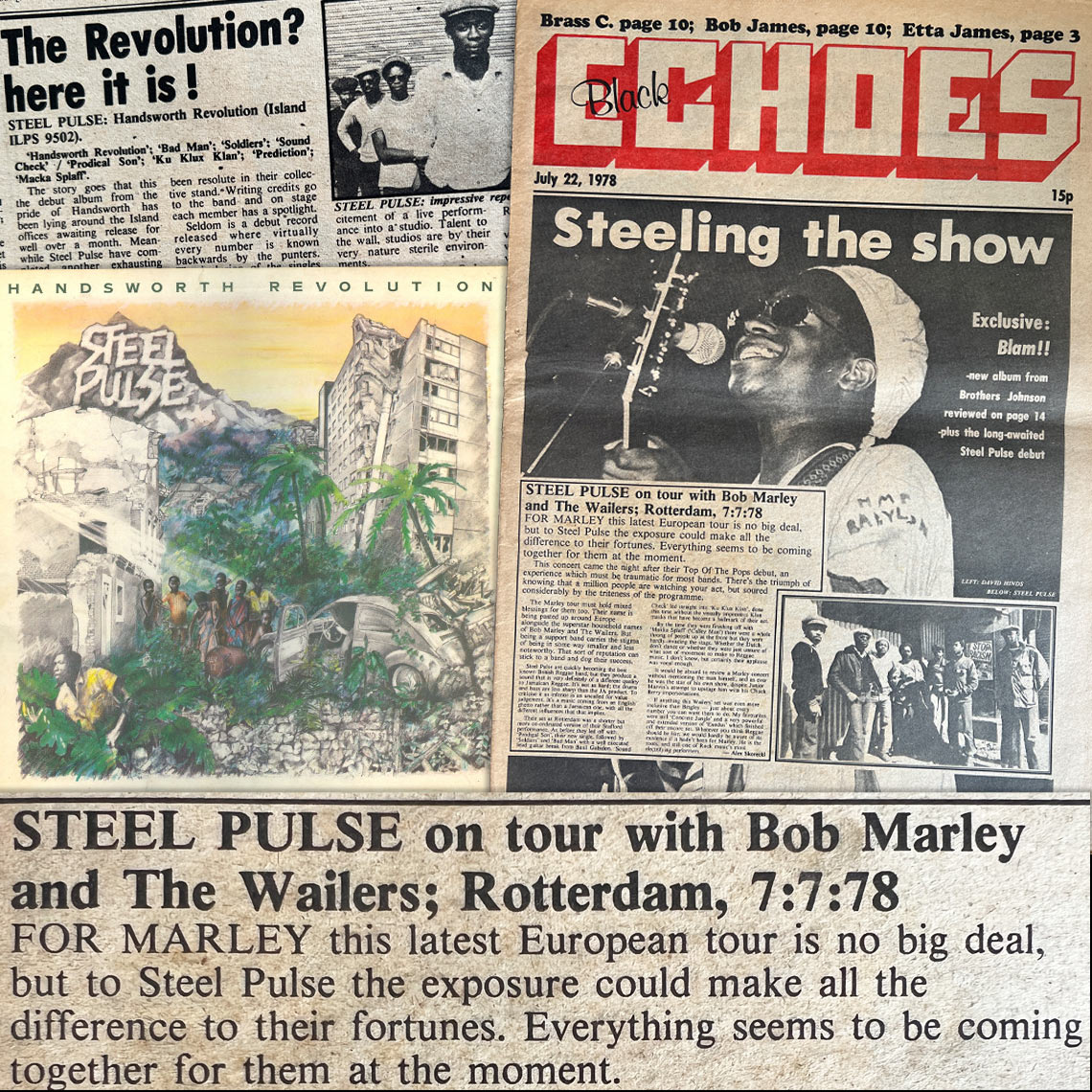

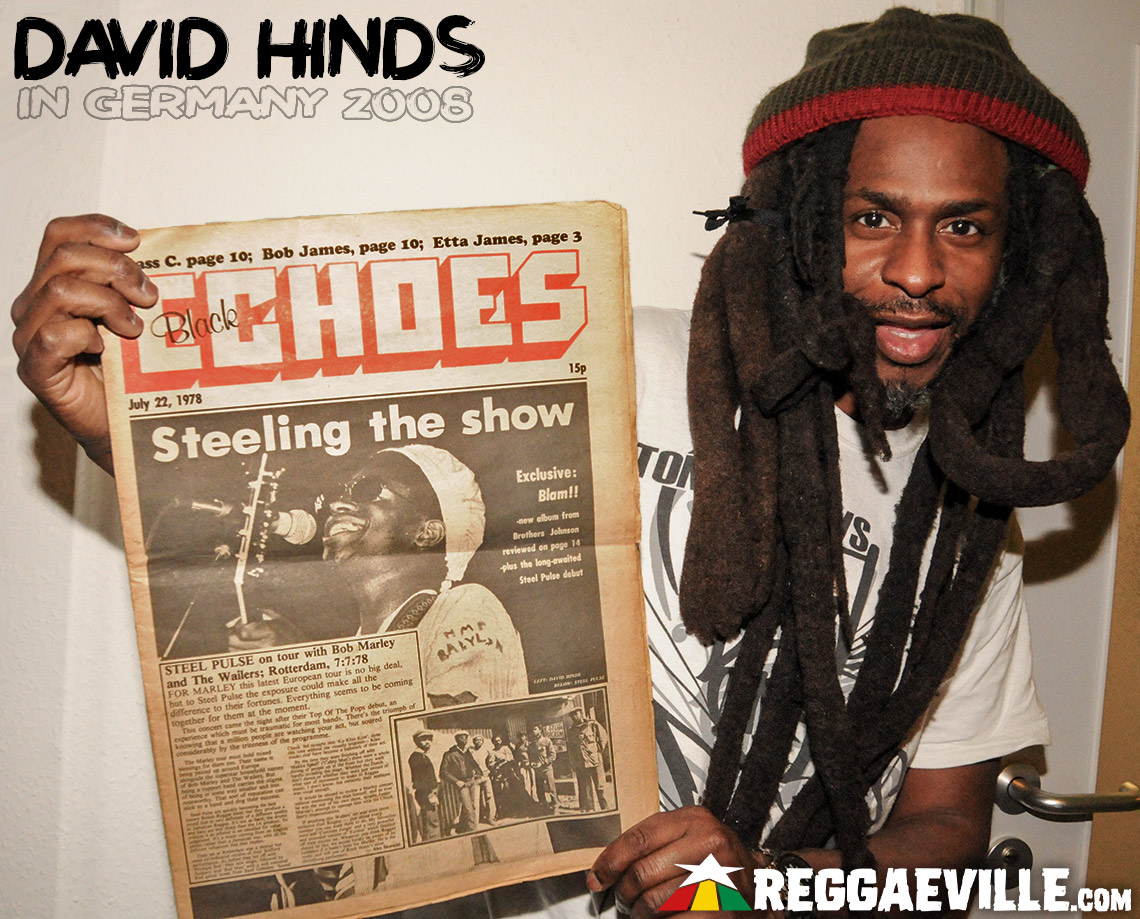

In 1978, Steel Pulse came to the attention of Chris Blackwell, who signed the group to Island Records for what would be a trilogy of groundbreaking albums that helped to define the sound of British reggae. Handsworth Revolution (1978) and its lead single Ku Klux Klan contained both the uncompromising social commentary and musical intricacy and depth that came to typify the band’s output. The same year, Steel Pulse opened a string of European dates for Bob Marley, who later referred to the group as a personal favorite. Steel Pulse followed up the success of Handsworth Revolution with Tribute to the Martyrs (1979), and then Caught You (1980), before moving to Elektra for a second trilogy of albums, starting with the seminal True Democracy in 1982, and followed by Earth Crisis in 1984, and the Grammy Award-winning Babylon the Bandit in 1986.

Though pressure from record companies would see Steel Pulse pursuing a more commercial sound through the eighties and nineties that the band would ultimately regret, they nonetheless achieved a number of benchmarks during this era, contributing a song to the soundtrack of Spike Lee’s critically acclaimed film Do The Right Thing (1989), and performing at the inauguration of American president Bill Clinton in 1993. The return of Steel Pulse to the production of more militant roots reggae came first with 2004’s African Holocaust, and most recently, with the release of Mass Manipulation in 2019. True to form, Mass Manipulation takes on diverse and pressing social issues, from racist policing, to global warming, to human trafficking, all in heavy reggae.

In this first installment of a three-part interview, David Hinds looks back at the earliest days of Steel Pulse, the Black British context from which it emerged, and the band’s path from local recognition to international acclaim.

Next year marks 50 years of Steel Pulse. How does that make you feel? You don't look old enough to have started a band 50 years ago!

I don't look old enough, but I sure feel it! “How does it make me feel?” Well, you're saying five decades, you're saying half a century. To be honest with you, as Burning Spear said in one of his songs, “I and I survive”, and it's all about trying to survive this industry and the wickedness that came with it. So I feel blessed that we're able to weather the storm, for want of a better phrase.

Because it's been 50 years, I’d like to start by asking you a few questions about your earlier days. How did your experience growing up as a Black youth, in particular in Birmingham [UK], shape your outlook and also give shape to the music that Steel Pulse made?

Well, put it this way: I was taught at school that the first seven years of one's life are the most significant; the first seven years sort of set that precedent. And so even though it's a long time ago, I still look at many things through those eyes when I was seven and growing up. And growing up in Britain at the time was kind of a weird one, simply because although we were born in Britian and recognized as British, that never necessarily equated to all the British standards and expectations, because of the family background I came from, which was from Jamaica. And it was all about that migration that took place that I had no knowledge of until I was a teenager, growing into an adult, and then it all started to make sense. Britain, being the colonial power over Jamaica and so many other islands, asked the Jamaican populace to come to the motherland to repair the country after World War II.

So did your parents come to Britain in the 1940s?

Well, the war ended in 1945. And by 1948, that invitation to the Caribbean started an influx of colonial subjects. So my dad went first, and then raised enough money to send for my mother. She came over in ‘55 and then ‘bam,’ here I was, the following year. So being in Britain now, but coming from a Jamaican culture, with the language, the food, you name it, I was raised as a Jamaican in its fullest sense. My parents didn't know how to fully adapt. They adapted for the sake of work, but as far as the other British cultural type of things, like the food, what they listened to, and what they talked about, it was all foreign to the Caribbean populace that flowed into Britain. So for me growing up in England with a Jamaican background, I found it a bit weird adjusting. Did I experience racism? Hell, yeah! You know, the local neighbors would call us ‘Blackie,’ ‘Nignog,’ and ‘Wog,’ which was a common name that they called black people back then, which was an abbreviation for Gollywog. I don't know if you know what a gollywog is? It's like a little puppet minstrel kind of thing used as a motif on jars of jam. So that was a slogan: "Hey gollywog, why don't you get back in your jam jar?" Things like that. So those were the kind of slogans that we were exposed to in British society; we weren't quite fitting in.

So with regards to your generation, I'm curious about how that experience was reflected in the reggae coming out of the UK. Thinking about the other great bands that came up alongside Steel Pulse like Aswad, Misty in Roots, Matumbi, etc: Do you think there's something that links you together? Is there a common ethos or outlook that you could point to that stands you in contrast to the reggae that was being made in Jamaica at the same point in time?

Funny you should say that, because myself, Brinsley [Forde], and Dennis [Bovell] get together now and then and do some work. We had an album that we started about four years ago, but COVID slowed that down. But I know Dennis is going to be bouncing back on it. So the answer to that question, is that I believe our connection was the fact that we're coming from parents from the Caribbean. But they had a London perspective on things, whereas Steel Pulse came from a Birmingham perspective, which is very much different because those from Birmingham were seen as country bumpkins at that time. But the connection between us got even closer when we started to go into the music and delve into the happenings of the record labels, where we realized that we all had one thing in common: We were on a major record label and the next thing you know, we’re kicked off it. So those are the kind of connections we had. And with Misty in Roots, for example, there’s a guy called Poko, and every now and again we made phone calls and had a chinwag about what's going on. Misty in Roots were probably the most diverse of the four bands you've mentioned. They weren't into this record label business, like becoming famous, having a yacht in the back and a mansion behind you; that kind of thing. They were more on the roots level, whereas, when they even did tours, they slept on their own buses; no hotels, things like that. They were strictly all about doing the thing from a grassroots level. But we all shared the same aggression when it came to the record companies and how they treated British reggae at that time.

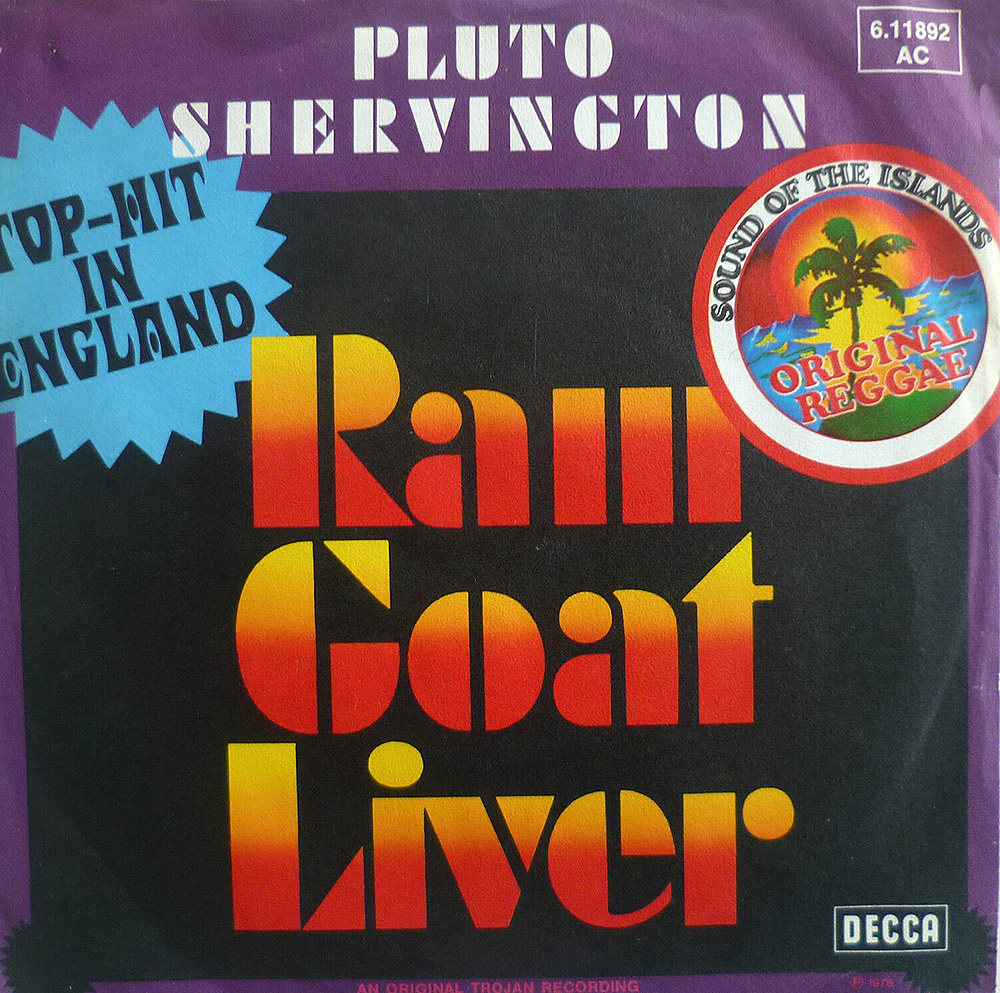

Radio stations as well, they weren't easy. The punk rock era was really the era that made an indentation as far as reggae making a mark in Britain. Because previously, you had the flashes in the pan, like your Johnny Nashes, Pluto Shervingtons, Dandy Livingstons, and all those guys. They all had gimmicky-type songs where, once the DJ plays a track on the radio, he'd be laughing about it. “’Ram Goat Liver,’ what does ‘Ram Goat Liver mean?’” So the DJ ridiculed reggae music. They made a mockery of the whole thing. And that was Britain's kind of invitation or gateway for reggae music at that time. And then, like I said, bands like ourselves started to make that whole shit become a different playing field and got a lot more serious with it. The rest is history.

It's interesting that you mentioned the punk scene. Can you help me understand the alliance of sorts between the reggae and punk scenes in the UK at the time? I know you guys opened for various punk bands. How did you perceive each other? What was is it that drew the two movements together?

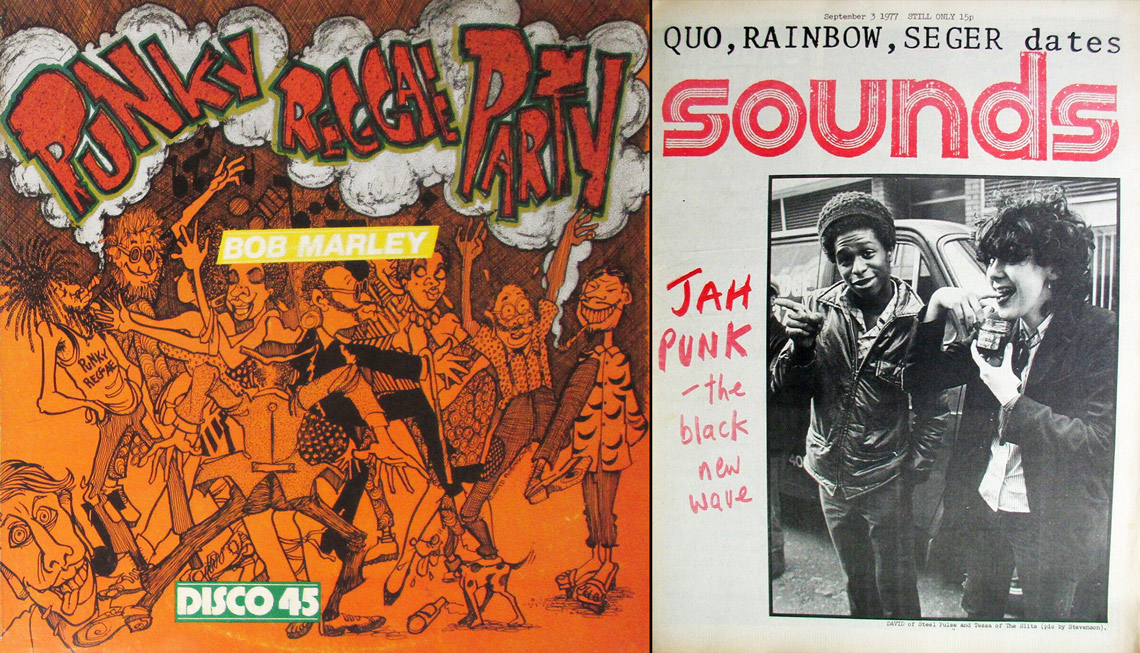

In all honesty, it was like night and day, chalk and cheese, oil and water, you name all the opposites. However, there were one or two people in the industry who saw the connection, and who saw an angle of getting our music established by using the punk rock genre. But for people like Bob Marley, I mean he wouldn't have known anything about punk rock music. Coming from Jamaica, he wasn’t used to seeing these weirdos with their hair all colors of the rainbow, their ears, nose and eyebrows pierced with safety pins, but it was the punk’s way of rebelling against the system. Bob had to be briefed and educated to know what's going on in the British music scene. It would have been someone like Don Letts that was familiar with the industry who probably encouraged Bob to recognize the union of both genres. Bob’s Punky Reggae Party song testifies to that. And he went out there and he started mentioning all the big names - The Clash, The Jam and all those acts - and lo and behold, the British public bit on it.

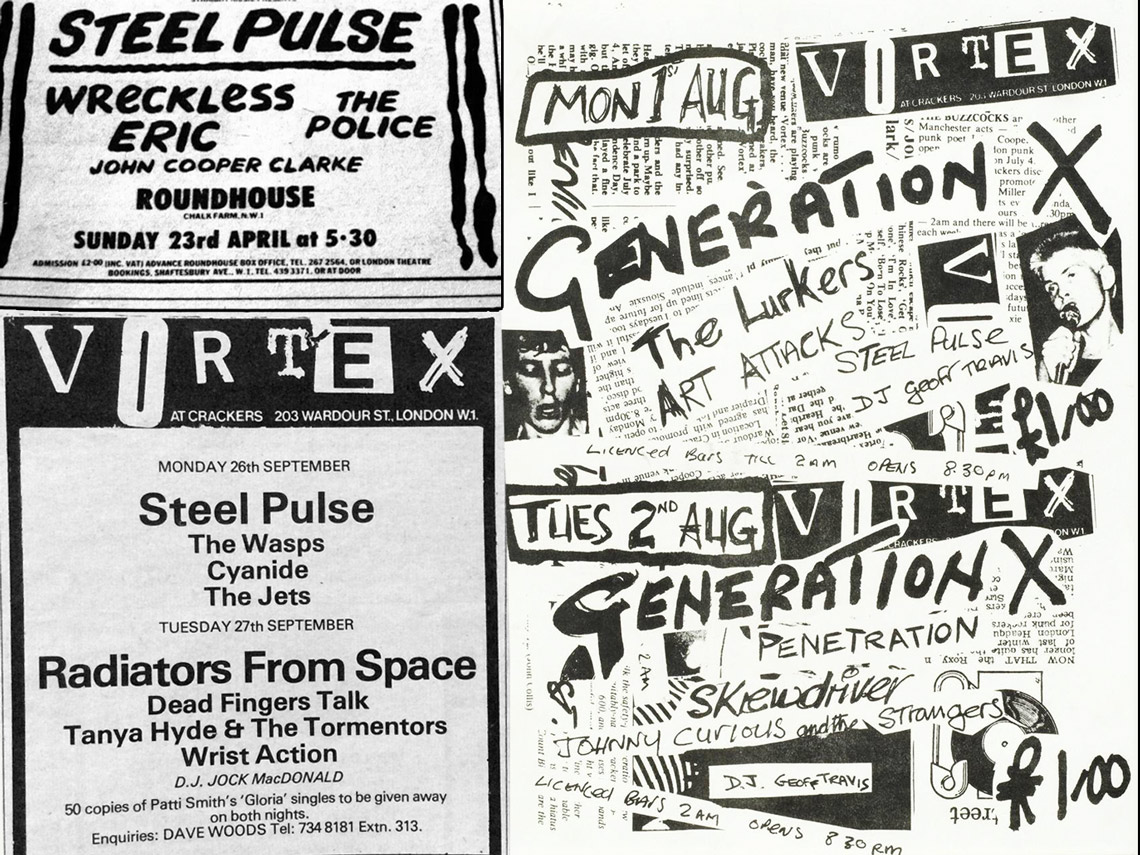

So there's a lot to the very early start of the whole punk rock era. Initially a lot of reggae bands didn't see themselves related to it. The general consensus was that it was white people’s music, noisy and non-melodic, with lyrical content that had nothing to do with our energy. Plus we were too busy trying to find our culture, going back to Africa, to hell with you guys, that kind of thing. But then we had our management saying, listen, this is the way to go. With reluctance, we said all right, let's see what you're on about. And so we did our first show at a place called The Vortex. We were opening for Generation X, that had Billy Idol as their frontman. And there were all these guys in the audience spitting at us! And we said, what the hell's going on here!? And at one point, our frontman at the time stopped the music and said, "anybody who spits or throws beer bottles or beer towards the stage, will get the microphone stand planted in their cranium!" That stopped them.

It was only afterwards that we learned that this was their way of saying, gosh they really dug what we did. We adapted to this new lifestyle quickly, making several trips to and from London, 120 miles in a vehicle, between destinations. And dates were being added rapidly - one minute you're at The Vortex, the next minute you're at the Marquis, then the Roundhouse, next minute you're at the 100 Club - all typical punk rock venues. It became impossible to go back to Birmingham each night, knowing we’d have to come back to London to do the show the following day. And so we started staying there, either sleeping in a van or crashing out on a friend's floor in their living room.

But did you guys socialize with the punks or did you tend to stick to yourselves?

Ultimately we did, but not at first. Over time, it became cool to be hanging out with the punk rockers. You started to understand why they behave the way they behave and that it's all about anarchy - they've seen the system for what it was and anything that the system disapproved of, they were into. The punks just made their mind up that anything the establishment was going to say yay or nay to, they'd do the exact opposite. So we said, after all, gosh, I kind of like that! It's a bit like us, really, but from a white man's perspective. And before you know it, we're out there with Generation X, the Adverts, and then on a whole UK tour with one of the most popular bands at the time, The Stranglers. I remember when Hugh Cornell, the lead singer, was arrested, and we all hosted a benefit show for him. So Steel Pulse was invited alongside punk acts. We started to become like a token, or like the reggae band to really be part of. And we'd be attending their parties and stuff, and their parties were some weird ones, man! You know, women stripping, things like that. We'd go, what the f* is that! Dipping their tits in people's beer, guys drinking it, all that kind of shit we were exposed to. It was just the punk rock way of liberty, and we just had to get used to it.

So from there you mentioned Bob Marley. How important was opening Bob’s 1978 European tour to the early success of Steel Pulse? How do you think back on that?

When I think back, I would say it's the most significant milestone of the band’s career. And what makes it even more significant is that the man's no longer with us. I guess if he was around still, like Herbie Hancock or Carlos Santana who we performed with, it might not have had the significance as it does now, in regards to how I feel about it. So when it comes to the milestone, that's at the top of the list. Obviously, playing the inauguration of Bill Clinton was also a big one, but this one I'd say is at the top of the list. And it happened at a time where the band could barely string three or four chords together. All we knew was that we had a sound that sounded like no one else's.

We also had a publicist that saw all the angles under the sun back then. You know, they invented stories - they even had us advertised as much younger than what we really were at the time. So it was all the gimmicks, the bells and whistles that came with hype and publicity, and we were a part of that in a very big way. Cops would come into our dressing room and the next thing you know, our publicists would say, "Guess what? Steel Pulse got raided! But they didn't find anything." And the people would say, "What!!??" In reality, all the cops did was say "Hi guys, how you doing?", but the publicists took it to the max!

Instead, they would say that they had come to our dressing room searching for drugs and they didn't find any. And bang, it was always all over the local paper, and magazines like Melody Maker, Sounds Magazine, and Black Echoes. So all the little gimmicky type publicity was there. So the Bob Marley tour came up, and we would have been fools not to do it - we jumped on it like a bum on a ham sandwich! And we've never looked back since - everything sort of fell in place at that time.