Steely & Clevie ADD

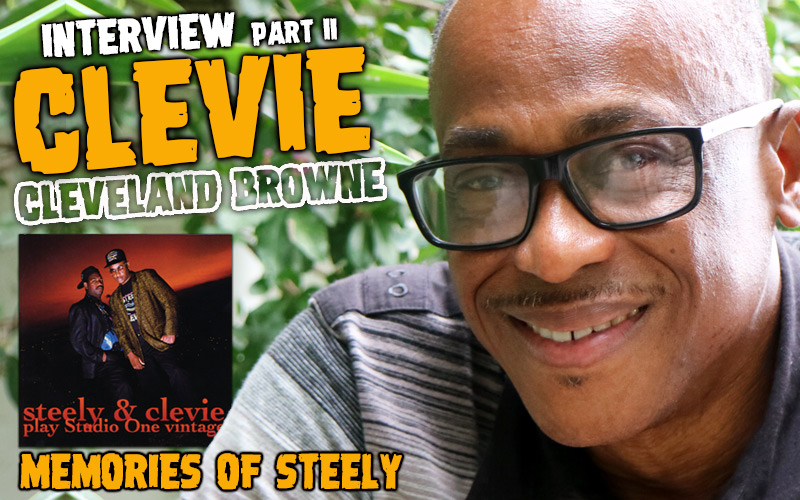

Interview with Cleveland 'Clevie' Browne - Memories of Steely

12/29/2019 by Angus Taylor

In Part 2 [read Part 1 here] of our exclusive interview with Cleveland Browne, he talks about working with Bob Marley, going digital for King Jammy, and why Steely was one of a kind...

I've got one more question about the pre-digital time. Can you tell me a bit about the work you did at Tuff Gong? And your encounter with Bob Marley?

(laughs) Tuff Gong I used to do sessions occasionally with friends, random people. But I was called on by Sangie Davis to work on Nadine Sutherland…

Starvation…

Starvation On The Land. And it was that same night when the session ended at about 3 in the morning, we didn't know Bob Marley was upstairs, and he came downstairs while the band was waiting to get a taxi, we never drove in those days. And Bob came down on the steps and we could hear him playing his guitar. I was kind of scared of it because I was saying “Bob Marley whoa” (laughs). You know I didn't even want to look at him! I just had a glance and heard him playing and he was composing Stiff Necked Fools at the time. And he said “Skip I want to lay this down now, you know? Make we go in the studio.” And of course I couldn't say no - taxi cancelled. (laughs)

And we went in the studio it was Sangie Davis on guitar, Steely on piano, Dalton my brother, and Left Toe again on bass. And there was another musician Pablove Black. And we laid down We Come From Trenchtown and Stiff Necked Fools. But I was kind of nervous as I thought Bob Marley was going to cuss some bad word or something. I had never encountered working with a man of that calibre before. I had worked with Bob Andy before that because Browne Bunch were called to play on tracks for Bob Andy but Bob Marley was the ultimate to me at the time as a reggae artist. And he was quite accommodating and understanding that we were youths and it went down well. It was a great experience for me.

And I discovered also some of the techniques he used. He recorded all his tracks with a click which makes it easy to remix today because tempos will always waver no matter how great a musician is. So I embraced that and adopted that as well. In doing live sessions I like to record with a click to ensure easy remixing.

The reason I asked about that is to open up a topic that I've really fascinated by. You’re associated with the digital era and that's your place in history but Bob Marley, Familyman and Tyrone Downie were experimenting with digital rhythms before that. It just wasn't the time for it to go industrywide.

Chim Cherie, yeah.

And also the digital drums arm on the Natty Dread album…

Right and I must say that inspired me or confirmed to me that that this could work. Because everybody was saying “Don't bother with that digital thing man, it's foolishness you're doing”. And when I heard So Jah Seh - that was the first song with the rhythm box that wasn't programmable, it just had a pre-set (sings beat). I got a TR-606 Roland, that was my first programmable machine, very small with the lights running across (laughs) The old TR-606 it was the best thing since sliced bread. Because I could now put in the beat that I felt, you know? I input what I want instead of just accepting the pre-sets. I was now able to program.

Then the Oberheim DX - it was the drummer for Third World band, Willie Stewart, he went on tour and he brought the Oberheim DX. And then the DMX came out which should have been better and he decided to sell it. Prior to that I bought my first drum kit from him - my father, I should say, bought my very first acoustic kit from Willie Stewart. He always came to my house gravitating to musicians, he loves the family, so he used to come out by and hang out with us. I also attended all the Third World band shows. Transmigration - always had some concept concerts and I liked that, during that era when Jamaican band started experimenting and getting deals with major companies. Inner Circle, Zap Pow band, Native those bands were going into experimental music.

My experimentation was digital and Steely saw eye to eye with me on that. Steely said “Well I have found a bass”. I understand that actually Flabba got him that bass which when he got it was playing flute type sounds. Very small keyboard and it fell from Steely and it wasn't working and he gave it out to a technician and when it came back it was playing bass! (laughs) And the bass sound complemented the Oberheim DX perfectly. The sounds were just made for each other.

Tell how you first went to Jammy’s?

Steely again! (laughs) Alright, what happened was we started the very first digital recordings for a sound system in August Town called Black Star sound system. They wanted to make some specials and for economic reasons we could record because we made some demos on cassette. When he heard it he said “Hey you could make the rhythms”. So we started making rhythms which were the very same rhythms we took to Jammy’s as demos.

And everything just fell perfectly along a timeline journey in that in 1985 Jammy’s recorded Sleng Teng and we were looking for a producer who would accept that digital thing because everybody was saying “No that's foolishness man, go live”. But what could we do that made us stand out like a sore thumb? (laughs) So we said “Digital”. The fact was that at the time the technology was growing. I started hearing Stevie Wonder and a couple of American bands that were using drum machines and so on. So we said “This is something that is going to continue. It's not going anywhere and then major companies will be signing those bands. It won't be going anywhere, so adopt it for reggae.” And so we did.

So Jammy’s now came about because when Steely did recordings for Black Star he said “You know I should check Jammy’s” but for the excuse to go there “Jammy’s owed me some money from some live sessions from like a year before”. So he was going to go there and say Jammy’s “I've come for my money - and listen to this at the same time.” (laughs) When Jammy’s listened to it he said “It sounds alright” but after a couple of years he admitted to us he was blown away by it. He just acted modest about it. He said “Come Sunday, let us start some recordings”.

And so we did the first recordings - Sweet Reggae Music, Nitty Gritty - and from there it was just hit after hit after hit. The new sound hit after hit after hit. The other thing is there was another drummer, I think Benbow, he came there with a drum machine similar to mine but he was playing it live and it wasn't synchronising right. So when I brought mine and programmed it they were all blown away to see that. They didn't know it was programmable they thought it was just the pads you hit and you record it. And it was just hit after hit for us. Clarks Booty rhythm and hit after hit. And that alone proved to us that that is the way to go and nobody could deter us from that - to go digital.

Let's talk a little bit about the stuff you did for Penthouse and for Gussie Clarke. Rumours in particular has been cited by historians as ushering in in the more conscious reggae era of the 90s…

Right. At Jammy’s I started and we used to play like straight grooves and one day I decided to start swinging the reggae. In In Crowd I had that experience as well. Back-A-Yard was a swing groove. It was that kind of groove with a swing. So Telephone Love I decided to also swing but instead of the traditional rimshot I started experimenting pitching down rims and changing sounds and that was the drum sound on Telephone Love. And of course, the orchestra stabs, all those sorts of things, introduced that to the reggae. But Germain always wanted us to come over to his which was next door and he didn't want us to go there! (laughs)

Yeah and the Rumours beat was just to sound check for the session. Gussie called us to do some sessions and we were just jamming. And the engineer was checking the sounds - kick snare near blah blah blah - and then we said “This track sounds like it could be recorded” and we recorded the track. I think it was Mikey Bennett who came with Rumours and Telephone Love went on it after that, and we made an album out of it eventually.

At that time I was of course learning about copyright and all that I brought to the fore. Not just at Gussie’s studio - to many producers the concept of the many musicians that create the track being composers and that they should be given the rights for the music… many producers there never really took to that and some of them thought we were troublemakers! (laughs) When we were just standing up for our rights. So we stopped working for some producers who didn't embrace that because they thought that the singer was deserving of all the rights for the song. I said “Well unless it's an a capella and vocal only, the song is considered a demo until complete. If it means that music goes on it around that melody structure and the lyrics, the musicians should get some benefit from that.”

You and Steely did an interview with Red Bull where you said something very interesting about how you started to make some of the rhythms for your own label less melodic because some of the deejays couldn't stay in key.

Right. We felt that, Steely being out of the ghetto, we had a soft heart for struggling youths. Some of them have very good lyrics, had something to say that could help Jamaica and help the world at large to understand what they were feeling. So as a means of expression we said “Alright you know what? If they're not able to hold a key, let's make the music more minimalistic and more drum-driven”. We did that with When with Tiger for instance and we stripped it down and it was more drum-driven. The Giggy rhythm, the drums were playing the main bass, so we stripped it down and used less chords where you can actually relatively identify that the artist is off key. We did it deliberately to accommodate artists who might not be able to deliver melodically. But they had something to say.

As Steely and Clevie, your own production unit, which works are you most proud of?

Wow! (laughs) I'm particularly happy every time we bring about a new beat like Poco Man Jam. It was a new beat and new creation that never existed in dancehall all or reggae before. Like when we also went to the Giggy beat. I would say that new era of sound which still is copied today. People have been making over the Giggy rhythm. What it has become it's like you hardly hear anyone else creating newness. Reggae has always been reggae. Apart from like Sly. Respect for his different beats that he created. I really respect Sly. And rate him! (laughs) Outside of that you have hardly heard newness, so when Steely and Clevie came with a new beat that has always been the most impacting on me as a memorable era.

But also working with some major artists like Billy Ocean, Gwen Stefani from No Doubt. The manner in which they approached their vocalising on the tracks. The time spent was quite inspiring for me. Voicing Billy Ocean, we voiced 10 hours and some artists from Jamaica would voice for an hour or two at the most and then say “Tired man” and say “That's it, let's take that.” And we would say “No, we are the producers. I am not happy with it as yet.” I'm talking before Pro Tools. No autotune existed then.

And the first artist, a deejay, that was accommodating for spending the time to get the thing right was Shabba Ranks. When we did Ting-A-Ling-A-Ling it took 5 hours voicing that song. I respected Shabba from that day as an artist. He signed for a major company and we gave him a talk on that day and we said “Remember you’re signed to a major. You're not competing with Lieutenant Stitchie and Beenie Man and so on. It’s the world you're competing with - Michael Jackson at the time - and so you have to go hard or go home!” (laughs) And Shabba really went hard until we were all happy. Simple.

But the attitude is also another component, not just hitting the notes right but to get the notes right with the right attitude. Those artists who were signed to majors, they discovered being produced by us that it was work. It's work. And you have to just work until you get it right - until the producer says that it's right. When I worked with Gwen Stefani, Gwen made a simple statement she said “Voice me until I drop”. You know? Because other guys in the band No Doubt were saying “We can fix that electronically”. We were accommodating saying “If you're tired let us know” so we were being nice but she said she was willing to go all the way.

Caron Wheeler from Soul II Soul was also very inspiring as an artist and I was exposed to another level of vocal intonations that I never experienced before. Before I put any EQ on the voice, that breath, there was a sizzle that identified clearly then that artists needed to be healthy. The things that alcohol and smoke will do to your voice when you remove that, it creates a different level. Despite me saying that, sometimes the abuse can create a sound as well but as you grow older there won't be long…

Diminishing returns…

Diminishing returns. And I'm proud to say from day one Steely and I had always been totally clean from any artificial abuse. No drugs, not even beer. Never even drank beer. Beyond that even in our studio we never allowed smoking in there. Capleton came with his flag men with red gold and green flags and we said “No smoke” (laughs) “Wave the flag but no smoke”. And I learnt that from Bob Marley…

Really?

Despite being a heavy weed user, at Bob Marley’s studio the sign was there “No smoking, no drinking”. He never smoked in his studio. And Chow who was his maintenance man said that the smoke particles will get into to the equipment and after time you're going to be hearing static and all sorts of noises. And we followed that. So Bob was more inspiring than just the music.

What was it like working with Dawn Penn on the remake of No No No? Partly because you worked at Studio One but also because you've talked a lot about publishing and that song is a particular publishing minefield…

Oh man! I've heard various stories about Dawn Penn. But now you're going to get it from the horse’s mouth. I have seen interviews I think where Dawn had totally forgotten how it went. Dawn came to Mixing Lab with a tape and said she was going to sell the tape. I asked if it had music on it she said “Yes” but it was during the time when there was a Studio One anniversary - 30th I think. Where they had a show and a lot of the artists from Jamaica who lived abroad came down. I think BB Seaton and some of those who lived in various countries like Alton Ellis.

And when Dawn came to the gate we invited her in and said “By the way do you know that one of our favourite songs - both Steely and myself - was No No No?" And the bass-line - Steely went crazy over that bassline the sound of it and all that. Which is the kind of sound he makes digitally with his bass sound as well. Having worked at Studio One I know there was a bass amplifier with an 18-inch speaker in it and they used to mic the speaker. Sometimes if the bass amp was turned up too much you can get distortion (sings No No No bassline) like something baffling and you can't roll it off, it's recorded because of the speaker itself. So we went for that kind of tone at times. Adding a little distortion and so on, you know? I don't want to give away too much! I'm giving away too much! (laughs)

But anyway we gave her some advance and recorded No No No. The vocal was a guide vocal and it became the vocal that was released. Recorded in the control room and it happened with two songs apart from that one by Dawn Penn, Baby Can I Hold You by Foxy Brown. It was the same thing with demo vocal. They say the first cut is the deepest and it really happened. I've seen it where Dawn has said that it was a recording for Steely And Clevie Plays Rocksteady - there was never an album like that. So I even had to correct Dawn the other day and said “Look you have missed it, it was Steely And Clevie Plays Studio One Vintage”. So making use of the opportunity with the artists all being in Jamaica we decided to start writing down a list of songs that we would have loved to record for the main purpose of presenting some of our favourite oldies to a new generation. We thought with the Steely and Clevie name it would be accepted by the young generation who might not have been into the old Studio One.

For us, both Steely and Clevie, a hit song can always be a hit song packaged the right way for the era, for a new period of time. We’d record and make it sound more modern but with the same groove and feel. And we did an entire album having selected various artists and songs that we thought what needed a new life. Songs that we couldn't find on a compilation from Studio One all together. And we did just that - Steely And Clevie Play Studio One Vintage.

Out of which it was released two years before and it went out to the radio stations in Jamaica and there was actually an active period of time of payola. We never ever joined payola we never did that. And it never got the play that we thought it would get until someone in the States identified that song as a potential hit. It was Clive Davidson at VP Records. He linked up a friend of his at RCA Records and then Atlantic and he decided to sign the song.

It got signed to Atlantic records in 1994. It became a hit, two years after the recording. Then the disc jocks in Jamaica started calling my house “How come you don't give me a copy of that?” I said “Check your box, you got it two years earlier”. (laughs) You know they didn't realise they had it. And yeah that was one of the songs I'm very proud of. From Steely and Clevie from when you asked me earlier and when I spoke about the different styles and so on, as a recording that song I should say is one of my most impacting. And as such one of my favourites. Apart from that Sean Paul and Sasha I'm Still In Love With You with another big hit.

Another Studio One…

Which again proved to me that a hit song can always be a hit song presented at the right time in the right package with the right distribution as well. Because without that it can be a failure - the right marketing.

What’s a good memory of working with Billy Ocean?

We got Billy Ocean to do a special for Silverhawk sound. (laughs) First of all he didn't know what a special was. We said “Billy we want to do a special for the sound system” and he said “What's a special?” So we had to play him an example and he understood and he's quite musical. So he did it and killed Stone Love and the rest is history! (laughs)

You've helped some of the live musicians from your early era to be honoured by the government. It must be nice to be able to do that considering what you said earlier about making sure that musicians get composing rights. And also after people's initial reaction to the digital that it was anti music!

(laughs) One thing I'm really saddened by is that like Mikey Boo who was a mentor to me, he now has physical disabilities. And he never learned to program. Where has Calvin McKenzie who lost a leg, he found other ways to trigger a bass drum with a mic and things like that. But Mikey Boo never went that route. And if they had a vision, no musician should really be incapacitated for having lost a limb because there are ways around it. I remember there was a rock band, was it Led Zeppelin?

Def Leppard. Yeah the drummer lost an arm and still drums.

Yeah, so he found a way. I saw it is important to promote the formation of the counterparts to many of the organisations, the collection management organisations, in Jamaica. The whole thing started with the formation of RIAJAM The Recording Industry Association Of Jamaica of which I was chairman for five years. All of that gave birth to JAMS Jamaica Music Society where, as I mentioned earlier, I'm still on the board. So all of these are support organisations for the industry generally to ensure the collection of royalties from the various sources and to engage in reciprocity with the rest of the world.

Because if we don't have the equivalent organisations, they won't represent us. We won't be represented by our counterparts because they want the bilateral agreements. Apart from one organisation where I have managed to foster a unilateral agreement with, out of the UK, PPL, because the government has not yet passed a law to allow for performers to collect royalties. As in the case of PPL where if you clap your hand on a recording and it gets played and you’re credited you are supposed to be paid. For use in clubs, any venue or radio. Copyright law was amended recently to allow us our extension of the term but that component was left out for the performers to ensure their rights. But we're fighting for that right now to get that done.

Because some of the older musicians who cannot perform any more and their songs still get played, so they can be paid. That's sort of like a pension for those entertainers. I'll stand up for that right till I die (laughs). A lot of people are getting away with murder. We are just introducing an insurance scheme as well for the producers. I think JCAP probably has one now for the writers but for producers we found that in Jamaica entertainers will die and there is no money! So we have fostered a deal now with a major insurance company in Jamaica to have a group insurance catering to the industry. And the fees the payments are very small, all based on the numbers.

JAMS now has over 1,000 members meaning that Jamaica has over 1,000 producers. Which is mind-boggling for me. And of course, you'll have Steely and Clevie productions but Steely is credited separately from me because I do production separate and apart from Steely. And vice versa. But genuinely over 1,000 that is amazing. So all those persons who endorse the insurance policy have some protection at the end of the day.

So it's a life insurance?

Life insurance. That never existed before.

Because even now you see people trying to do crowdfunding for sick or destitute musicians…

And we have distributed will forms to all members as well. Because I think it stems from way back in the days most Jamaican men don't want to think about death. Like even the words we use we don't say “See you next week” - we use positive words instead. Earthstrong and certain words.

Like Peter Tosh and all those men never spoke about death but we all will go that way one day (laughs) and as such they don't prepare our wills. So JAMS has issued will forms to the members and encouraging that because some members’ wives don't know where the money is. They don't know when you have artists who have accounts in other countries and it will stay there and nobody knows about it. Sad reality but it's reality.

Finally what are your memories of Steely? At this point in time how would you encapsulate him for someone who didn't know him as a person?

(big laugh) You need to extend your stay! Steely was an amazing person. There were certain things about Steely that the general public did not know. Steely had a photographic memory for one. An amazing memory. He would remember all the songs he played from day one. And he would keep things in mind until he decided to erase.

For instance, working with Gwen Stefani she had a bodyguard that worked with the CIA and they decided to test him because they heard about this quality. They will give him like 100 digits, random digits and letters. He would look at it for about 30 seconds and we would do the recordings and then at the end of it all they asked him about the list that they gave him. And he would start and they’d say “He's wrong” and he would laugh and say “Check it backwards!” And he would say “You wrote the F a little larger and tilted it to the right. And the Q which was the 32nd digit was written a little below the line”. And everyone in the room would give him their phone number and at the end of the session after working out songs he'd say “Your number is 518...” and “Yours is this backwards!” He was like that.

But I think it's great that Steely didn't go to a tertiary institution. If he did he might not have been the Steely we know today. Outside of that Steely had appeared like a tough character to a lot of people. There was a time when I remember Steely knocked out a black belt once. He was sleeping at 12 Tribes and this guy who was a black belt came in was like “Wake up!” and he got up and just knocked out this guy! And he was that kind of character until we started working together. I think a yin and yang thing was happening and we found a balance. We had to deal with various kinds of characters in the industry, so there were times when I would take the forefront and say “Alright I'll deal with this person” and Steely would deal with that person. Perfect balance.

Steely had a loving heart despite all of that. When you get deep down to the soul of the person. Steely used to go into the ghettos, he took me down there as well and he would unite conflict in gangs. And those things will never be publicised. But he did. But because the connection was the music. Despite if you are JLP or PNP everyone would love the same music, you know? Whether you're PNP or JLP or this gang of that gang and the respect was there for Steely, as a man who also was from the ghetto and knew ghetto life. So that loving heart was there. He was compassionate. When he got ill towards his last, he called me one day and said “Clevie, you will never disrespect anyone who comes to beg at the stop light or to wipe a windscreen and a man who has no leg or whatever” because he now knows what illness is.

But he also had a foresight where he could see things before it happened. One of my most impacting moments was a year before Steely passed I picked him up at home and we were driving together to the studio. He was staring like into another world and he just made a statement and said “Clevie I'm going to die”. I had to stop the car and say “Steely don't ever say that again. No, I don't want to hear that”. But deep down inside I knew that he had predicted other people's deaths. People who seemed healthy and he said “That man is going to die soon”. So it was bothering me. That happened in 2008 and he ended up in hospital in Jamaica in December 2008 and by September 2009 he died. It was like I knew it was coming but I didn't want to accept it.

He could predict things and foresee things. That was an attribute that he had. And it happened in the studio many times when we had some producers who we had never experienced before would come along and say “Make 5 tracks for me today”. And Steely would say “That man is planning to rob us”. And we would say “Alright, pay us now for half of the session and the rest when we finish” and it always worked out like “Oh I'm waiting for a cheque to be cleared” or “Some money is coming from New York” or something (laughs) and he’d say “See I told you, eh? This man doesn't have the money.”

Many times he would see things before it happened. So when we made a new track Steely would kick off his shoes and run around the studio. At Mixing Lab you could go around the back of the board and all that and he would run and say “This is a hit!” And they were always hits when he said that. And I miss that about him where are we could know without a doubt that this was going to be a hit. Nothing could stop it.

We did a track for this taxi driver. And we said “Look we're going to use this to show that we can hit any artists but we want that person to have a role in the whole thing”. So we said “Come to the studio at 7 in the morning” because that person has to also want it, you know? If he didn't show up at 7 we’d say “You're not serious”. It's an odd time, 7 in the morning, but the man showed up. And we made the song and it hit. Now he felt that he could do it again without us and it never ever happened again. That was his only and last hit.

So we find that that's the missing component. Many times artists would get like the “village lawyers” as we called them. Like their cousins or some relative would tell them “No you don't need those guys, a your voice this”. But it's not just their voice. It is what you do with the voice. What kind of music complements the voice? How is the voice produced? A lot of components that are missing when they go elsewhere.

We named a few artists. Steely named Garnett Silk. He came to us as Garnett Smith. Before that he was a DJ called [Little] Bimbo. And Steely said “We're going to change your name, we're going to call you Garnett Silk because your voice has a little silky air to it”. And so it was. (laughs) And I named Natty King. I listen to a lot of different music styles. I was listening to Nat King Cole, my parents, my father especially was a record collector and he had songs from the 30s, coming up from 78 RPM. He had turntables that could spin at that speed. I got exposed to Nat King Cole and some of the early greats like Frank Sinatra and so on. And it just dawned on me that there could be an artist called Natty King Cole - a dreadlocks (laughs) but Steely said “No, let's call him Natty King". And Natty King came about instead of Natty King Cole. Bushman, we gave him the name “Bushman”. He came to us as Junior Buckley. Because we think a name is important. There's no point in being great if you have a name that doesn't connect with the public.

Like Sly and Robbie, you and Steely were very contrasting characters.

(laughs) Yes, yes!

That's obviously how you put a production duo together. You can't have two of the same people.

Usually you have fights if they are the same! I still would always say Steely and I never had a fight but we did have some musical differences in terms of the direction something was to go. But we’d usually find a common ground. We’d usually find it and it worked out well. Because when Giggy was being made for instance, I was using the drums to play the bass line and that is what introduced that “dudu” and then Steely had the “dungu dungu” with more notes. And both of them worked so none actually dominated the song throughout.

Read Interview Part 1 here